forum

library

tutorial

contact

This is No Way to Run

A Railroad Or a Utility

by Marty Trillhaase

Lewiston Tribune, July 11, 2018

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

This is No Way to Run

by Marty Trillhaase

|

BPA is about to commit $500 million during the next 20 years toward the four dams on the lower Snake River.

Little of that money will go toward turbines or power generation.

Two broad mandates govern the Bonneville Power Administration.

Two broad mandates govern the Bonneville Power Administration.

Under the Northwest Power Act, it has to mitigate for the debilitating effects its dam system has on salmon and steelhead runs.

And Congress expects BPA to at least break even on the hydropower it sells to utilities. It's failing at both.

As the Tribune's Eric Barker reported Sunday, BPA seems poised to undermine the former while doing next to nothing to help with the latter.

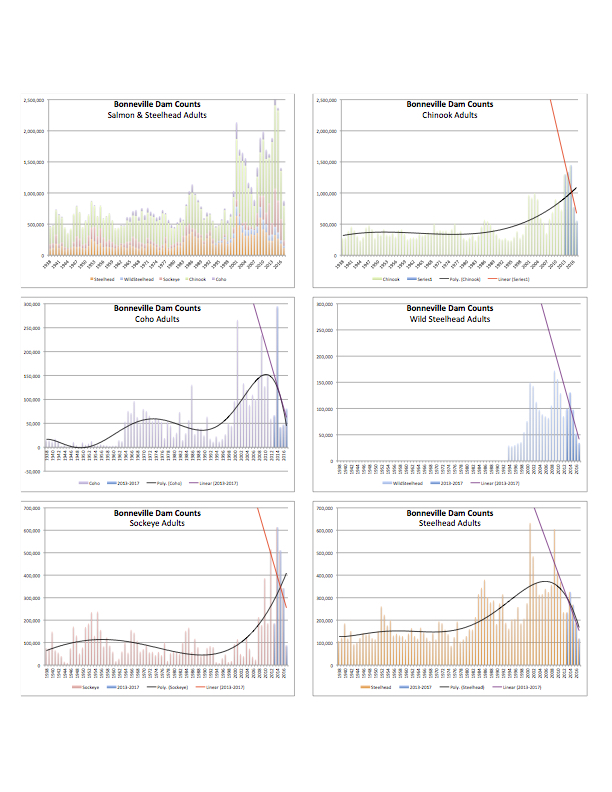

After BPA spent more than $15 billion the past two decades on fish recovery, populations are plummeting.

As few as 500 of the wild B-run steelhead returned in 2017 to the Columbia and Snake rivers. That's down from about 15,000 in 2004-05.

Some 4,100 wild spring-summer chinook returned to the Snake River in 2017, down from 21,000 two years earlier.

Eleven sockeye salmon arrived at Redfish Lake in 2017, less than half the number during the prior year.

When the hydropower system was reaping gold by selling its excess electricity on the open market, you might have excused some of that.

A decade ago, BPA could expect to get anywhere from $80 to $100 a megawatt selling electricity it didn't need to markets such as California - a tidy sum considering it cost BPA about $36 a megawatt to generate it.

That allowed BPA to ease back on rates charged to its own customers.

Today, however, the region is awash with surplus electricity - thanks to cheaper natural gas and the advent of renewables such as wind and solar. With that has come a cost curve that's been flipped on its head. Solar, for instance, produces electricity precisely when customers need it - during the busiest time of the day.

So BPA is unloading its surplus at a loss - something like $20 a megawatt. The public power agency has burned through virtually all of its reserves. And as Barker noted, some of BPA's clients now look longingly at the lower rates available on the wholesale markets.

The more of them who bolt from BPA when their contracts expire in another decade, the fewer customers will remain to share the rising costs. More of them will be tempted to go independent and the process will repeat itself.

"It's called a death spiral," says Boise economist Anthony Jones.

So you'd think BPA would respond by doing more to protect fish while finding a way to make its electricity more cheaply.

Instead, it plans to cut back on fish mitigation - trimming spending on the $300 million program by $30 million in the next fiscal year. For that to make any difference, you'd expect the cut to be permanent.

If spending more than $300 million a year isn't recovering fish, what will $270 million get you? Here's betting fish advocates and the federal courts will be asking some tough questions.

Reducing overhead - even at the expense of fish - might seem callous. But at least it would be expedient if done to free up money to buy technological fixes that restored BPA's profitability.

Instead, BPA is about to commit $500 million during the next 20 years toward the four dams on the lower Snake River. Little of that money will go toward turbines or power generation.

So once again, the agency is left at the mercy of hostile market forces, leaving you to wonder: What will BPA run out of first - fish or customers?

It's the kind of situation that inspired the phrase: "It's a hell of a way to run a railroad."

Related Pages:

BPA at a Crossroads by Eric Barker, Lewiston Tribune, 7/8/18

Will Idaho's Lame Duck Governor Extend His Reach? by Marty Trillhaase, Lewiston Tribune, 6/18/18

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum