|

The Columbia River Basin is North America's fourth largest, draining about 258,000 square miles and extending predominantly through the states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana and into Canada. It contains over 250 reservoirs and about 150 hydroelectric projects, including 18 dams on the Columbia River and its primary tributary, the Snake River.

The Columbia River Basin provides habitat for many species including steelhead and four species of salmon: Chinook, Chum, Coho, and Sockeye.

One of the most prominent features of the Columbia River Basin is its population of anadromous fish, such as salmon and steelhead, which are born in freshwater streams, live there for 1 to 2 years, migrate to the ocean to mature for 2 to 5 years, and then return to the freshwater streams to spawn.

Salmon and steelhead face numerous obstacles in their efforts to complete their life cycle. For example, to migrate past dams, juvenile fish must either go through the dams' turbines, go over the dams' spillways, use the installed juvenile bypass systems, or be transported around the dams in trucks and barges. Each passage alternative has associated risks and contributes to the mortality of juvenile fish.

To return upstream to spawn, adults must locate and use the fish ladders provided at the dams. Once adults make it past the dams, they often have to spawn in habitat adversely affected by farming, mining, cattle grazing, logging, road construction, and industrial pollution.

Reservoirs formed behind the dams cause problems for both juvenile and adult passage because they slow water flows, alter river temperatures, and provide habitat for predators, all of which may result in increase mortality. Other impacts, such as ocean conditions and snow pack levels, also affect both juvenile and adult mortality. For example, an abundant snow pack aids juvenile passage to the ocean by increasing water flows as it melts.

Given the geographic range and historical importance of salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River Basin, local governments, industries and private citizens are concerned about the species' recovery. For example, some Indian tribes living in the basin consider salmon to be part of their spiritual and cultural identity, and fishing is still the preferred livelihood of many tribal members. Treaties between individual tribes and the federal government acknowledge the importance of salmon and steelhead to the tribes and guarantee tribes certain fishing rights.

Efforts to increase salmon and steelhead stocks in the Columbia River Basin began as early as 1877 with the construction of the first fish hatchery. Now, states, tribes, and the federal government operate a series of fish hatcheries located in the Columbia River Basin. Historically, hatcheries were operated to mitigate the impacts of hydropower and other development and had a primary goal of producing fish for commercial, recreational, and tribal harvest. However, hatcheries are now adjusting their operations to ensure that they support recovery or at least do not impede the recovery of listed species.

As dams were built in the 1900s, attempts were made to minimize their impacts by installing fish ladders and bypass systems to help salmon and steelhead migrate up and down the rivers. In the 1980s, several other actions were taken to increase salmon and steelhead populations, including:

- a treaty between the United States and Canada limiting the ocean harvesting of salmon;

- the passage of the Pacific Northwest Electric Power Planning and Conservation Act (P.L. 96-501), which called for the creation of an interstate compact to develop a program to protect, and enhance fish and wildlife affected by hydropower development in the Columbia River Basin and mitigate the effects of development; and

- the beginning of major state, local, and tribal efforts to address habitat restoration through watershed plans.

None of these efforts proved to be enough, however, and in the 1990s, 12 salmon and steelhead populations were listed as threatened or endangered under the ESA, resulting in the advent of intensified recovery actions. The 12 listed populations are:

- Endangered - 1991 - Snake River Sockeye salmon

- Threatened - 1992 - Snake River Fall-run Chinook salmon,

- Threatened - 1992 - Snake River Spring/Summer-run Chinook salmon,

- Threatened - 1997 - Snake River steelhead,

- Threatened - 1998 - Lower Columbia River steelhead,

- Threatened - 1999 - Lower Columbia River Chinook salmon,

- Threatened - 1999 - Lower Columbia River Chum Salmon

- Threatened - 2004 - Lower Columbia River Coho salmon.

- Threatened - 1999 - Middle Columbia River steelhead

- Endangered - 1999 - Upper Columbia River Spring-run Chinook salmon,

Endangered - 1997 - Upper Columbia River steelhead

- Threatened - 2004 - Upper Columbia River steelhead

- Threatened - 1999 - Upper Willamette River Chinook salmon,

- Threatened - 1999 - Upper Willamette River steelhead,

|

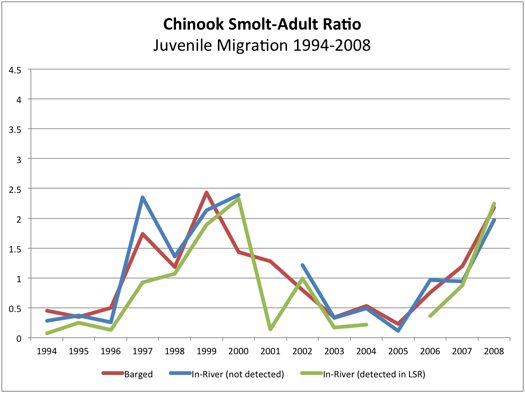

Smolt-Adult Ratio above 2% is considered

necessary for a sustainable population.

Source:

www.fpc.org/survival/css_sars_stdycat_queryv3.html

Smolt-Adult Ratio above 2% is considered

necessary for a sustainable population.

Source: Fish Passage Center

www.fpc.org/survival/css_sars_stdycat_queryv3.html

|