forum

library

tutorial

contact

Unleashing the Snake

by Paul LarmerHigh Country News, December 20, 1999

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Unleashing the Snakeby Paul LarmerHigh Country News, December 20, 1999 |

As salmon runs dwindle,

the Pacific Northwest ponders a once-unthinkable option:

Dismantle the Dams

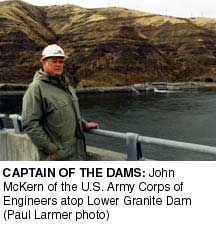

LOWER GRANITE DAM, Idaho - A stiff wind blows from the west this blustery fall day, but it doesn't bother John McKern. Wearing a hard hat with his name in black letters across the front, the clean-cut, burly 54-year-old looks like a sea captain as he leans against a railing and gazes down at the dark blue waters below.

LOWER GRANITE DAM, Idaho - A stiff wind blows from the west this blustery fall day, but it doesn't bother John McKern. Wearing a hard hat with his name in black letters across the front, the clean-cut, burly 54-year-old looks like a sea captain as he leans against a railing and gazes down at the dark blue waters below.

But McKern is nowhere near the ocean. Rolling hills of blond and chocolate wheat fields surround this "ship," which is in fact an immobile concretion known as the Lower Granite Dam. It is the uppermost of four federal dams that block the Snake River in eastern Washington on its way toward the mighty Columbia River. Built in the 1960s and '70s, the dams produce some of the Pacific Northwest's vaunted cheap electricity and create deep waters for barges to carry grain and lumber from this interior outpost to the world beyond.

McKern is a fish biologist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and, in a way, he is the captain of the Snake River dams. For in this brave new post-dam-building age, biologists have an increasing say in how federal dams are run. They have taken over because the famous salmon and steelhead runs that have used this stretch of river for tens of thousands of years on their way to and from the ocean continue to spiral toward extinction, and the dams have proven to be one engine of their destruction.

The Snake River run of coho salmon has already vanished, probably in the mid-1980s. In this decade, Northwestern tribes and conservationists convinced the federal government to give the four remaining stocks of Snake River salmon protection under the Endangered Species Act. The listings have pushed the federal agencies in charge of the river to make all sorts of adjustments to the four dams to help fish survive, and McKern, a 30-year veteran of the Corps, has been in on all of them.

Today, he and Nola Conway, a public-relations specialist with the Corps' Walla Walla District, descend into the bowels of Lower Granite to show off one of 12 enormous, 60-ton fish screens. The screens deflect more than half of the juvenile salmon, or smolts, away from the dam's turbines and into a narrow pool of water, where they are sucked into a pipe and carried hundreds of yards below the dam. Most of these collected fish are piped onto a fleet of barges and trucks, then floated or driven past eight federal dams to the waters beyond the Bonneville Dam, on the Columbia River, 50 miles west of Portland.

The Corps started transporting fish in 1968. This year it spent $3.5 million to barge and truck 19.3 million fish, and McKern says 98 percent of those fish survived, a rate that "might be as high as when the river flowed naturally." Fish barging may have saved some of the Snake River runs from extinction already, McKern claims, especially during the drought years of the 1970s, when flows were very low and temperatures in the reservoirs were high enough to kill fish. If he had his way, the Corps would be allowed to barge every fish it could catch.

But these days McKern and his barges sail against a strengthening headwind, even within his own agency. He and the communities and industries that rely on the federal waterway are being forced to envision the day when the dams will stand functionless, like mothballed battleships in a harbor. Many scientists and conservationists believe the dams still kill inordinate numbers of young salmon, because the number of returning adults continues to drop. All the technological tinkering in the world won't bring the runs back, they contend, and only one bold approach will: bulldozing the earthen portion of the four dams so that this 140-mile stretch of the Snake can once again flow as a natural river.

Conservationists call the concept "partial breaching," because the dams will still stand. But the term makes McKern bristle. "Partial breaching is sort of like being a little bit pregnant," he says. `The fish-passage system and the turbines will be left high and dry," and the river will flow around the dams.

Five years ago, breaching was considered so radical few environmentalists would touch it. Today, it is center stage in a natural-resource debate more fierce and complex than that over the spotted owl.

A deadline drives the issue: This spring, the Clinton administration must decide which measures are needed to restore the runs under the Endangered Species Act. The federal agencies that run the hydrosystem - the Army Corps, the Bonneville Power Administration, which markets power from federal dams, and the National Marine Fisheries Service - are racing to finish a couple of massive studies on the various options to recover the fish and assess their potential economic impact on the region.

With each passing day, the tension builds in places like Lewiston, Idaho, an inland "seaport" 30 miles above the Lower Granite Dam and 465 miles from the Pacific Ocean. Industries that rely on the dams run ads in the local paper, touting the wonders of barging and the plight of wheat farmers who will suffer without cheap barge transportation. Conservationists, Native American tribes and fisheries organizations counter with full-page ads in The New York Times condemning the dams as fish killers and calling on presidential candidate Al Gore to take a stand. Both sides bury reporters in a blizzard of scientific and economic papers.

As crunch time approaches, the Clinton administration and the federal agencies are looking for a way to delay the dam-breaching decision, at least until after the 2000 presidential election. No one can predict what kind of bounces election-year politics will bring, but thus far, the tribes and environmentalists have not succeeded in making salmon a national issue, the way "ancient forests" became national in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

However, the lack of a national constituency doesn't mean the dams won't be breached. While some in the Pacific Northwest fiercely oppose breaching, and have much to lose if it happens, others in the region have much to lose if the dams continue to stand. Electricity users, Alaskan fishermen, loggers and ranchers will pay a heavy price if the burden of recovery falls on them instead of on those who benefit from the dams.

Ultimately, Congress must authorize the removal of federal dams, and that won't happen unless there is a consensus within the region, or a national push that breaches local opposition. Neither exists now.

But, unlike the spotted owl, the salmon is loved by almost everyone in the Pacific Northwest, and no one has said they want to see it become extinct. If the Snake River runs don't show any signs of recovering - and soon - the region's leaders may accept breaching as the only option. That's a possibility even the dam-building Army Corps now recognizes, says Nola Conway.

"It's not a matter of if we breach, but when we breach," she says, standing next to McKern. "These dams won't be here forever, and I can foresee a time when there isn't such polarization and we can agree on how to do it."

Having your fish and eating it, too

Having your fish and eating it, too

The road toward breaching has been long and painful. Scientists estimate that 16 million ocean-fatted salmon once entered the mouth of the Columbia River yearly, heading toward spawning grounds scattered across four states and a sliver of Canada. But soon after the first salmon cannery was built in 1866, the numbers began to plummet. Early fish advocates sounded the alarm.

"Nothing can stop the growth and development of the country, which are fatal to salmon," wrote Livingston Stone, a member of the U.S. Fish Commission, in 1892. "Provide some refuge for the salmon, and provide it quickly, before complications arise which may make it impracticable, or at least very difficult. Now is the time. Delays are dangerous."

The warning was accurate. Fisheries collapsed, and hatcheries pumping out millions of salmon each year didn't help, and may have even hurt the wild runs. Scientsts now recognize that hatchery fish dilute the genetic purity of the wild fish and compete with them for limited food resources.

The drive to develop the Columbia River Basin intensified with the industrial age. Historian William G. Robbins notes that mechanized farming and logging, large-scale industrial mining and numerous small dams may have destroyed as much as half of the basin's fish habitat before the 1930s.

At the heart of the development drive lay the vision of a tamed Columbia River, irrigating arid basins, lighting cities, running factories and transporting goods. With the onset of the Great Depression, regional boosters capitalized on Franklin Roosevelt's massive public-works program to kick off a federal dam-building era. The first dam, Bonneville, was completed in 1938, followed in 1941 by Grand Coulee, which alone blocked off 1,100 miles of fish-spawning habitat.

The building of the dams consolidated the Army Corps' position as the dominant waterway agency in the region, and created a new federal entity, the Bonneville Power Administration, which sold the electricity produced by the dams. Together, the two agencies would dominate the Northwest.

Fish advocates stood little chance against dam-building, so they focused on trying to make the dams fish-friendly. They forced the Corps to build a fish ladder at Bonneville, which got adults past the dam. But the bigger problem, and one that historian Keith Petersen says Corps officials knew about from the start, was how to get smolts heading downriver safely past the dams.

Not only did the pressure generated by the dam's whirling turbines kill the smolts, but fish that were fortunate enough to get sent over the dam's spillway away from the turbines suffered from a form of the bends caused by the supersaturated gas created by the plunging waters. And without a current to push them through the reservoirs, the usually swift 14-day journey was extended by weeks, making smolts more vulnerable to predators such as pikeminnows, which thrive in slack water.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers maintained that its dams were benign. One Corps official told Congress in 1941 that Bonneville Dam's turbines were "absolutely incapable of hurting the fish. If you could put a mule through there and keep him from drowning, he would go through without being hurt."

Congress authorized the four lower Snake River dams in 1945, but for a decade Oregon's and Washington's increasingly vocal fisheries agencies helped delay the construction of the first Snake River dam, Ice Harbor. But, as Keith Petersen notes in his 1995 book, River of Life, Channel of Death, fish advocates could not outflank the Cold War: A call for more power at the Hanford nuclear complex in central Washington eventually convinced Congress to fund the dams.

For the Inland Empire Waterways Association, a coalition of farmers and entrepreneurs in eastern Washington, the new dams were a ticket to prosperity. The chain of reservoirs created by the dams - Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite, in ascending order - turned the Snake into a river of commerce for farmers; entrepreneurs hoped that new industries would soon gather on its banks to take advantage of cheap electricity and cheap transportation.

But fish advocates did not give up. In 1970, the Northwest Steelheaders Council and seven other conservation groups sued the Corps to stop the fourth dam, Lower Granite, and a fifth dam planned farther upstream. Larry Smith, a Spokane-based lawyer who represented the Steelheaders, says, "We never expected to win, but we hoped to raise awareness about the impact of dams. In some ways we succeeded, because that was it for dams - the fifth dam was never built."

Smith, an avid fisherman and bird hunter who used to haunt the rich bottomlands of the Snake before the dams flooded them, says he is happy to see fish advocates once again aiming their sights on the dams. "I'm all for breaching," he says. "Those dams should never have been built in the first place."

That's a sentiment also held by Michelle DeHart, who heads the Fish Passage Center in Portland, which monitors the number of returning Columbia River salmon. "How do we admit that we went too far in developing this system?" DeHart asks. "How do we admit that we need to undo something we've done?"

From barging to breaching

Steve Pettit remembers well the day in 1975 when the waters behind Lower Granite Dam backed up into Lewiston:

"I cried my eyes out," says the bearded, curly-haired fish biologist for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. "I was in a jet boat and we went down the river below Lewiston to where the slack waters were surging and we just rode them back toward Lewiston.

"I was thinking of how the beautiful stretches of water where I had caught steelhead after steelhead on a fly the year before were now a hundred feet underwater."

"I was thinking of how the beautiful stretches of water where I had caught steelhead after steelhead on a fly the year before were now a hundred feet underwater."

Pettit didn't know it at the time, but his professional life was destined to become intertwined with Snake River salmon. He became the state's fish passage specialist in 1981, when there was great optimism for the Snake River salmon. Congress had just passed the Northwest Power Act, granting the native fish equal footing with power production at the federal dams.

To strike the balance, the law created the Northwest Power Planning Council, composed of two governor-appointed members from the states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana. One of the first things the planning council did was endorse the Army Corps of Engineers' growing fish-barging program led by John McKern. Biologist Pettit was an early convert.

"The federal agencies predicted that with barging, Snake River runs would double in 10 years," says Pettit. "I believed them."

A decade later, when the first of the Snake River stocks were listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1991, the bottom had fallen out. The number of sockeye salmon making it back to Lower Granite Dam dove from a high of 531 fish in 1976 to zero in 1990. (The number has hovered in single digits ever since, despite a captive breeding program, leading scientists to call the sockeye "functionally extinct.") Wild fall chinook had tumbled from 428 adults at Lower Granite in 1983 to just 78 in 1990. Wild spring/summer chinook had dipped from a high of 21,870 fish at Lower Granite in 1988 to 8,457 in 1991.

Nonetheless, barging remained the central fish-recovery tool, along with providing more water from upstream dams in Idaho to "flush" the smolts more quickly through the filled reservoirs.

Flushing stung Idaho hard. Not only had the dams been the coup de grāce for its salmon runs - by 1978 the number of returning adults was so low that officials closed the general fishing seasons - but the federal agencies kept demanding more of the state's water for their unproven flush technique.

When the National Marine Fisheries Service determined in its annual Biological Opinion that the Corps' 1992 plan for operating the dams would not jeopardize the listed stocks, Idaho took the agency to court. In 1994, federal judge Malcolm Marsh ruled that the federal agencies were taking little steps "when the situation literally cries out for a major overhaul." He ordered federal biologists to work on a new plan with state and tribal biologists (HCN, 10/17/94). The judge's decision created an opening for an idea that had been first floated publicly in 1990 by then-Idaho Gov. Cecil Andrus. It was called drawdown - the rapid lowering of reservoirs to recreate riverlike conditions. Fish advocates rallied to the new cause, and in the late winter of 1992, the Army Corps of Engineers conducted a month-long test drawdown of Lower Granite Dam.

"We were left with a stinky hole filled with 20 years' worth of mud and muck and trash," recalls David Doeringsfeld, the director of the Port of Lewiston.

But the idea wouldn't die. In 1995, the NMFS (pronounced "nymphs") directed the Army Corps to further study drawdown and make a recommendation by the end of 1999. The Corps' initial studies showed that lowering the reservoirs for part of the year would destroy the barging industry, seriously reduce power production, and require $5 billion to redo the dams, McKern says. The cost of breaching all four dams, on the other hand, was around $900 million.

Suddenly, breaching didn't seem like such a wild idea.

Breaching gained more credibility in 1996, when a group of independent scientists commissioned by the Northwest Power Planning Council released its Return to the River report. The report advocated restoring more "normative" ecosystem conditions to rivers as the best way to help salmon and steelhead.

Meanwhile, a multi-agency team of scientists convened by NMFS released studies showing that breaching was the surest and quickest way to restore Snake River salmon. The PATH team (named for the model it adopted, Process for Analyzing and Testing Hypotheses) found that breaching has an 80 percent probability of recovering spring/summer chinook, and a 100 percent probability of recovering fall chinook, within 24 years.

The PATH team's conclusions rested on comparisons with other Columbia River salmon stocks that must negotiate the four lower Columbia River dams, but do not face the four lower Snake River dams. This includes the vigorous run of chinook in the Hanford Reach section of the Columbia.

"Our fish in Idaho are performing three to 10 times worse than lower stocks, even though they face the same environment below the Snake River, including the lower dams, the estuary, and the ocean," says Charlie Petrosky, an Idaho fish biologist on the PATH team. "What is it that is selectively killing the Snake River runs? It's got to be the dams."

In July of 1997, the scientific case for breaching spilled onto the pages of the Idaho Statesman in Boise, the largest paper in the state and part of the Gannett chain. In a brash, three-day series of editorials, the Statesman became the first in the region to advocate breaching. Not only would breaching recover fish, the editorial staff said, but it would benefit the region's economy (HCN, 9/1/97).

Fear on the farm

It would be hard to convince Roger and Mary Dye that breaching will help the economy. The Dyes, third-generation wheat and grass-seed farmers, live on the rich uplands south of the Lower Granite Dam, and, like most of the dryland wheat farmers within 50 miles of the lower Snake River, transport their wheat to market via river barge. Most of it ends up at the factories of noodle makers in the Far East, especially Japan, India and Pakistan.

These days, the price of wheat is at a 20-year low, and Mary Dye says dam removal would force her family to truck its wheat to the Port of Pasco on the Columbia River.

"I called a local trucker and he said our costs would go up 35 cents a bushel," she says. For the Dyes, that translates into an extra $20,000 a year.

Roger Dye says the breaching debate has caught most farmers by surprise: "Farmers around here used to laugh at dam breaching - `Ha! ha! what a stupid idea. It will never happen,' " says Dye. "But we're not laughing now."

Dye says he has no doubts that environmentalists will go after other dams if they succeed in breaching the four on the lower Snake. Why did they start with this 140-mile stretch of river? "Because there are only 1,500 people in Pomeroy and 2,000 in Dayton," Dye speculates. "This is the easiest place for environmentalists to target."

The wheat farmers are part of a larger economic community that relies on the Snake River waterway. Five ports handle roughly 3.8 million tons of grain bound for deep-water ports on the lower Columbia River. Farther downriver, another group of farmers pipe water from the Ice Harbor reservoir to irrigate some 37,000 acres of land reclaimed from the high desert steppe country in the 1960s. And the Potlatch Corporation's pulp and paper mill in Lewiston, with more than 2,000 employees, also sends one-third of its chips, paper products and lumber downriver via barge.

David Doeringsfeld, who oversees 250 employees at the Port of Lewiston, says a University of Idaho study commissioned by three of the ports showed that breaching would cost the Lewiston-Clarkston area between 1,580 and 4,800 jobs.

"Breaching would send this community back three decades," says Doeringsfeld.

In its mammoth draft Lower Snake River Juvenile Salmon Migration Feasibility Study, due out by Christmas, the Army Corps is expected to show that the economy in the vicinity of the dams and the reservoirs, as well as the port town of Lewiston, would be hit hard. But fishing and tourism industries upstream and downstream would prosper with a revitalized fishery. Overall, the region would lose 492 jobs over 20 years, according to Corps projections.

The loss of power production from the dams - about 4 percent of the region's supply - would cost the region $251 million to $291 million annually, according to the Corps. That could mean residential electricity bills climbing anywhere from $1.50 to $5.30 a month. The large aluminum companies that sit on the Columbia River could see their monthly electric bills rising anywhere from $222,000 to $758,000 a month.

Conservationists say the Corps' analysis needs to be compared to the $3 billion the region has already spent over the last decade to restore salmon and the billions more it will likely spend if the fish are not recovered. Also missing from the current debate, they say, is a discussion of how federal and state monies could ease the economic pain.

One conservation group, American Rivers, has hired economists to figure out how investments in transportation alternatives to barging - namely railroads and trucks - and water pumps at Ice Harbor could "keep farmers whole." One of the studies estimated that transportation rates for farmers would not go up if the federal and state governments invested $272 million in rebuilding railroad tracks and upgrading roads.

"We've postulated the question: If you could have all the benefits that you receive now from the dams without the dams, is there any reason we can't proceed with fish recovery?" says Justin Hayes of American Rivers, who grew up in rural Idaho. "We'd love to sit down at the table and figure all of this out."

"I don't think American Rivers knows anything about farming or the transportation of grain," says Doeringsfeld.

Frank Carroll, a former Forest Service employee who now works for Potlatch Corp. in Lewiston, says most of the mitigation ideas "are coming from a group of people that have never produced anything." But he says he has met informally with Hayes, and gives American Rivers muted praise for acknowledging that "it's not OK to hurt people to save fish."

"If that message spreads," says Carroll, "then we might be able to have a different kind of discussion."

Most economic players, however, aren't giving an inch, even those who are potentially big winners of a free-flowing lower Snake. The ports of Kennewick, Pasco and Benton on the Columbia River could see a substantial increase in business if farmers can no longer use the ports on the Snake. Yet in an essay in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the directors of the three ports slammed the American Rivers plan as unaffordable and based on one unproven assumption: that dam removal will actually save fish.

"Recent analyses by the National Marine Fisheries Service have indicated little value to fish recovery associated with dam removal," the directors wrote. "To date, the case has not been made."

A scientific scrap

Two years ago, the scientific case for breaching laid down by the PATH team appeared to be unshakable, but sometime in 1998, with the 1999 decision date for breaching drawing near, the federal agencies "went into their own little world again and started throwing some curve balls," says fish biologist Charlie Petrosky.

The first break appeared last April, when NMFS released an appendix to the Corps' EIS which cited data - the same touted by John McKern - showing that barged fish are surviving the ride down the Snake and Columbia much better than ever. If that's true, the report said, then something else must be killing a lot of the fish. Fix these other problems and breaching might not be necessary.

NMFS recommended another five to 10 years of study to help it figure out whether the barged fish were really surviving, or whether many were dying quickly after being released, as the PATH science predicted.

"We'll continue to triage these species for a period of time while we continue to answer the unanswered questions," Rick Illgenfritz, NMFS' director of external affairs, told the Associated Press.

"What's another 10 years of study going to do for the salmon?" asks Steve Pettit. "I'm convinced the federal government didn't think breaching would gain as much momentum as it has. All of a sudden it's staring them in the face, so they come up with new science to say we need more time to study the situation."

The step back from dam-breaching pleased Northwest politicians, not one of whom has come out for breaching. In July, Oregon Sen. Gordon Smith, R, pronounced the dam-removal discussion "essentially over."

The Clinton administration denied that it had made up its mind, but in November it released the first draft of a long-awaited report that once again raised the possibility that breaching was unnecessary. The so-called 4H paper, a precursor to the Biological Opinion expected in April, examines the four main causes of salmon mortality: hatcheries, harvest, habitat and hydropower. It lays out several scenarios for fish recovery, including one that calls for improvements in habitat without breaching.

"We've already improved the hydrosystem and reduced the harvest about as much as we can," says Lori Bodi, a BPA policy expert who sits on the team of federal agencies that produced the 4H paper. "We would ask: Where are the comparable improvements in habitat?"

Fish advocates agree that habitat degradation is a huge problem for salmon, but they say the 4H paper is slim on science and details. "Nowhere does NMFS say what projects it would do to improve habitat," says Justin Hayes of American Rivers. "Will we stop timber and grazing in the Snake River Basin, or stop irrigation to control water pollution? If improving the Columbia River estuary is important, how will that be achieved? Will the Port of Portland have to stop dredging?"

Conservationists and tribal leaders note with irony that NMFS is being asked to give its approval to a Corps plan to dredge the channel of the lower Columbia River, even as it builds its case for improving habitat in the same stretch of river.

NMFS director Will Stelle says his agency would only recommend against breaching this April if it thought other steps the region takes would be sufficient to save the salmon. "Are the governments of the region willing to make commitments necessary to recover these stocks without removing the dams? That's an open question," Stelle said at a November news conference. It was a remark some interpreted as putting pressure on the states to lay out what they'd do to improve habitat.

What those commitments will be has many in the region worried, and it's these worries that keep breaching alive.

"Is it sensible for taxpayers and ratepayers to maintain dams that deliver only 5 percent of the region's power and the nation's cheapest power rates, while continuing to pour millions of dollars into technological fixes that have so far resulted in $3 billion worth of failure at the dams?" asked a Nov. 18 Idaho Statesman editorial. "That's the economic tradeoff the region faces."

Bruce Lovelin of the Columbia River Alliance, a group representing a wide range of river users, told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, "Frankly, this could mean a regional civil war."

Strange bedfellows

Fish advocates say they are prepared for the Clinton administration, through NMFS, to punt on dam breaching this April. But they remain optimistic about their longer-term prospects, because they see the playing field shifting in their favor.

For one thing, the Indian tribes are getting more aggressive, and some of them have gambling wealth to give them legal and political clout. Four Indian tribes - the Umatilla, the Warm Springs, Nez Perce and Yakama - say they may sue the federal government for breaking treaty rights if it makes a no-breach decision.

"In 1855, we gave away more than 40 million acres for the right to keep fishing as we always have," says Donald Sampson, an Umatilla Indian who now heads the Columbia River Intertribal Fish Commission. "If the fish aren't there, then the treaty is broken."

Sampson says he has a team of 15 lawyers working on a "war plan." Damages owed the tribes could run into the "multiple billions," he says.

Then there are the Alaskans, whose powerful fishing industry fears that if the federal agencies avoid dam breaching, they will compensate by further restricting the harvesting of salmon in the Pacific. In a letter to Washington Gov. Gary Locke and Oregon Gov. John Kitzhaber, Alaska's Gov. Tony Knowles urged the Pacific Northwest to get on with the task of making the rivers safe for salmon. Snake River salmon "face a `killing field' of dams, turbines and reservoirs," he wrote. "As we all know, Alaska fisheries barely scratch this salmon population, accounting for only three-tenths of 1 percent of the human-caused mortality. Clearly, fishing is not the problem."

Backing Knowles is the state's congressional delegation, which has never hesitated to flex its muscle to defend Alaska's fishing industry.

The federal agencies are also changing. The Army Corps now looks at river restoration as its future, says Corps spokeswoman Nola Conway, pointing to the Corps' work in Florida to restore the channelized Kissimmee River.

And the Bonneville Power Administration, which supplies close to 45 percent of the Northwest's electricity, may well find it cheaper to lose a small portion of its power generation capacity than to continue spending hundreds of millions each year on a black hole of salmon recovery, says Pat Ford, the director of the Save Our Wild Salmon coalition.

Some utilities that buy power from BPA have already started to worry that if the salmon don't recover or go extinct, Congress - led by delegations in the Northeast and Midwest, where electricity rates are high - will take away their very low preferred-customer rates. One is Oregon's Emerald People's Utility District, which serves customers outside the Eugene area. Last May, Emerald shook the power establishment by supporting dam breaching.

"Should the U.S. Government ... fail to take steps necessary to protect the biological integrity of the Columbia and Snake rivers, the benefits that BPA has afforded the people of the Pacific Northwest will be taken away," the utility's board of directors wrote to President Clinton.

While other nonprofit public utility districts, co-ops and municipalities that buy BPA power have not followed Emerald's lead, several, including Seattle City Light, have said that breaching should be an option.

Five months is not much time for the region and the federal agencies to come up with a solution that everyone can live with. Longtime salmon combatants say that what's needed is fresh leadership. Oregon's Kitzhaber has made some efforts to bring the region's governors together to take on the salmon issue. But so far the other governors have shown little enthusiasm.

"Ever since the fish were listed under the ESA, people have retreated to their trenches," says Lori Bodi, who was the executive director of American Rivers before taking her current job with the BPA. "We've forgotten how to work together."

But, as every journalist knows, nothing motivates like a deadline.

"People are so worn out that maybe they're ready for a solution," says Bodi. "If not, we'll be back in court."

Fish advocates say any solution must eventually include breaching.

"We have a window of five to 10 years," says Scott Bosse, a biologist with Idaho Rivers United. "Breaching is not only possible, it is inevitable."

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum