forum

library

tutorial

contact

Administration's Salmon Approach

has been Tried - and Failed

by David R. Montgomery

Guest Columnist, Seattle Times - September 29, 2004

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Administration's Salmon Approachby David R. Montgomery

|

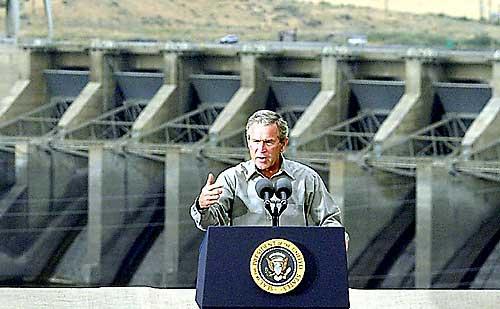

As the Pacific Northwest debates the Bush administration's recent proposal to count hatchery fish alongside wild fish in applying the Endangered Species Act — and its new plan to cut back critical-areas protections — it is worth considering the historical track record of such strategies in bolstering salmon runs.

As the Pacific Northwest debates the Bush administration's recent proposal to count hatchery fish alongside wild fish in applying the Endangered Species Act — and its new plan to cut back critical-areas protections — it is worth considering the historical track record of such strategies in bolstering salmon runs.

If those laboring to restore wild salmon in the Northwest look to the past, they will find an important lesson — salmon-management efforts that put too much faith in hatcheries, and too little effort into habitat restoration, have failed time and time again.

In the mid-1800s, an experimental salmon hatchery on the River Tay began trying to rebuild Scotland's salmon. William Brown argued that by rearing salmon in a hatchery and protecting young fish from natural predators, he would greatly increase the return of adult fish. For Brown, hatcheries provided an easy answer to the problem that overfishing reduced the number of fish to be caught: Just make more fish.

Because the Bush administration's new approach to salmon management seems to adopt Brown's vision, it is worth asking how well that vision has worked in the past.

During the wave of initial enthusiasm for salmon breeding, the British government established its first hatchery in 1868. Additional hatcheries soon spread across the British Isles, rearing salmon fry and then releasing them into streams and rivers. Although hopes were high that hatcheries would restock barren English rivers, the results were disappointing. British enthusiasm for reliance upon hatcheries soon faded as those hopes proved illusory for all but the few rivers where the natural habitat remained intact and productive.

Across the Atlantic, the first American salmon hatchery produced an impressive 70,000 eggs in 1870 to begin restocking Maine's rivers. Four years later, at the peak of the stocking program, more than 3 million eggs were shipped all over New England.

Initially, hatchery operations were seen as a key element in a broad program to rebuild the region's decimated salmon runs. But while the hatcheries were built, provisions for maintaining fish passage over dams, protecting habitat and preventing overfishing were implemented haphazardly, if at all. By the turn of the century, New England's once-thriving salmon runs were pretty much history.

Failure of early hatchery programs raised some serious concerns for fishery officials. In his official report for 1895, the U.S. commissioner of fish and fisheries, Marshall McDonald, concluded that reliance on hatcheries to sustain salmon production was unwise unless coupled with habitat protection and limitations on fishing intensity.

But this warning did little to dampen the enthusiasm for "salmon factories," which kept growing as salmon populations kept falling.

In the Northwest, the hatchery at Bonneville Dam became the central facility of a network of hatcheries throughout the Columbia River Basin. Still, the millions of fry released into the Columbia every year added little to the total number of fish caught in the commercial fishery that the hatcheries were supposed to enhance. Evidence for a beneficial impact of hatcheries remained elusive.

In the 1930s, John Cobb, dean of the College of Fisheries at the University of Washington, cautioned that overoptimism in the ability of hatcheries to maintain salmon runs in the face of ongoing habitat loss would eventually destroy the fishery.

Now, as we stand at the beginning of the 21st century, the Bush administration's policy seems tailored to lead us backward. The controversial and counterintuitive policy — which has been criticized by the administration's own panel of preeminent scientists — could extend protections to hatchery fish while denying protections to runs of legitimately endangered wild salmon.

By using large numbers of hatchery fish to mask the real problems of environmental degradation in the streams, the policy could open the door to continuing harmful practices. In other words, we seem poised to repeat the experience of England and New England.

Put simply, history shows little, if any, evidence that hatchery-based fisheries can be sustained over the long run in the face of habitat degradation.

Perhaps the most dangerous aspect of the historic reliance on hatchery production to sustain salmon populations is that the system has created the illusion that hatcheries can make up for the environmental degradation and overfishing that led to declining salmon runs in the first place.

This illusion deceived the public and policymakers into believing that we can sustain production of a valuable, renewable and culturally important resource while simultaneously degrading the environment and the conditions upon which that production depends.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum