forum

library

tutorial

contact

Washington's Struggle: How Far-Too-Slow

Salmon Recovery Impacts Orcas Like Tahlequah

by Jordan Rash

Tri-City Herald, January 17, 2025

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Washington's Struggle: How Far-Too-Slow

by Jordan Rash

|

Southern Resident Killer Whale named Tahlequahgave birth to a female calf that sadly died shortly thereafter. In her grief, she pushed her calf for more than 17 days across 1,000 miles. People around the world saw her grief across their TV and smartphone screens.

Southern Resident Killer Whale named Tahlequahgave birth to a female calf that sadly died shortly thereafter. In her grief, she pushed her calf for more than 17 days across 1,000 miles. People around the world saw her grief across their TV and smartphone screens.

And we're seeing it again today. Earlier this month she gave birth again; another female, who died shortly after birth. Again, Tahlequah pushed her calf through the cold waters of the Puget Sound.

We know SRKWs remain endangered at least in part due to environmental conditions (e.g., pollution, boat noise) and malnourishment. Unlike Biggs orcas that prey primarily on pinnipeds (i.e., seals & sea lions), SRKWs eat fish and prefer to eat Pacific Northwest salmon, specifically Chinook salmon, the largest and fattiest salmon available.

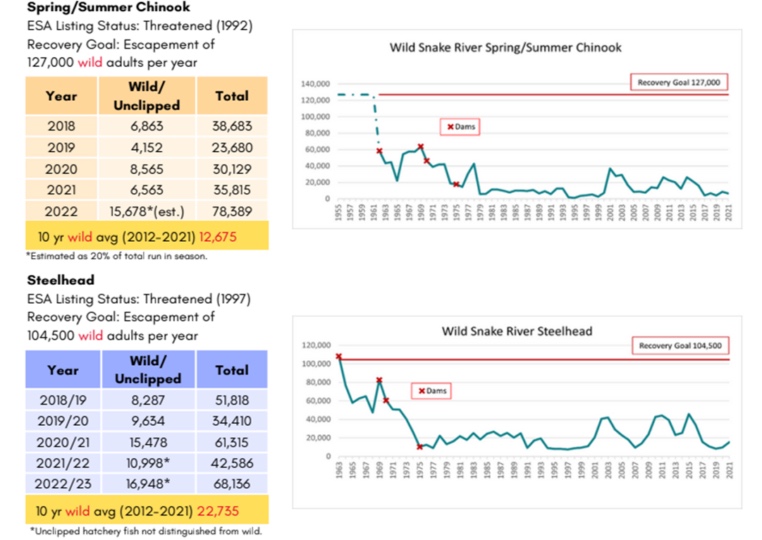

But, Puget Sound Chinook have been listed as "threatened" on the Endangered Species List since 1999, as have the Lower Columbia Chinook. Snake River Chinook have been listed even longer, having joined the list in 1992 due largely to the four lower Snake River dams blocking access to their historic spawning grounds. These are just a few of the 18 salmonids that can be found on the federal Endangered Species List.

The plight of salmon and SRKWs was the impetus for action in 1999 when legislators came together to pass the landmark Forests and Fish Law to protect salmon and steelhead habitat. Legislators also created the Salmon Recovery Funding Board to direct state resources toward salmon habitat protection, restoration, and other recovery-related activities. Combined with a number of other grant programs -- not the least of which being the Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program -- the state has been spending tens of millions a year on habitat protection, restoration and species recovery.

But this is painstakingly slow work. It takes years -- sometimes over a decade -- to identify habitats to conserve, work with willing landowners to acquire and/or restore their properties, complete the designs, construct the habitat restoration, and then monitor the outcomes.

And it's expensive. Look no further than the cost for replacing the road and highway culverts to provide for fish passage, which is contributing to the deficit in the state's transportation budget. But, we spent decades blocking fish passage while salmon stocks declined, which also had a cost in terms of lost opportunity (and more broken promises) to Native American tribes as well as in economic benefits from the commercial and recreational fisheries that help support rural economies across our state. Correcting those mistakes is costly, past due, but absolutely necessary.

The pace of salmon recovery work -- and difficulty in funding these complex projects -- is hindering our ability to recover salmon populations. According to the Governor's Salmon Recovery Office, the soon-to-be-published 2024 State of the Salmon Report shows that while some stocks (Hood Canal chum, Snake River Fall Chinook,and Lower Columbia Coho) are making good progress toward recovery, others such as steelhead, Puget Sound Chinook and Snake River Spring/Summer Chinook remain "in crisis."

Given the lack of measurable progress in restoring some of these salmon stocks over the past 25 years, some would question the utility in continuing to fund habitat restoration efforts. However, I cannot imagine a Washington without salmon and steelhead. To see these fish make their return to the rivers and streams -- including those in our metaphorical if not literal backyard -- inspires wonder.

Salmon are also core to the identities of Native American tribes, without which they are unable to perform certain religious ceremonies let alone nourish their communities. In addition, communities who rely on Pacific Northwest salmon (e.g., Westport, Neah Bay, Gig Harbor, even Seattle) for a significant portion of their economies would wither without the salmon on their longlines and the recreational fishermen who line the river banks and fill hotels, restaurants and tackle shops. And, as a fisherman myself, I will not be able to feed my own family, which utilizes wild fish and game for well over half of the proteins we consume.

Thus, we must continue to move forward like a salmon leaping to overcome a river obstacle. Salmon are part of our identity. Letting them go extinct -- and the SRKWs with them -- is simply not an option. We have to keep going and accelerate the pace of recovery to the furthest degree feasible in hopes that 2025 will be the last time we will see Tahlequah pushing a dead calf in grief.

If you have the time and the inclination, contact your state legislators and urge them to continue fund the critical salmon habitat conservation work -- such as the Salmon Recovery Funding Board and Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program -- so that future generations may also experience the thrill of seeing salmon spawning in our rivers and streams, and orcas breaching in Puget Sound in delight of full stomachs.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum