forum

library

tutorial

contact

Startling Sockeye Run Hits Columbia River

by Roger PhillipsIdaho Statesman, June 28, 2008

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Startling Sockeye Run Hits Columbia Riverby Roger PhillipsIdaho Statesman, June 28, 2008 |

Good snowpack and cold weather aid migration. But officials are still baffled.

Ten times as many sockeye salmon are returning to the Columbia River as last year, which could mean the highest return for Idaho's most endangered fish in more than 30 years.

The Columbia River sockeye run is already double the initial predictions and is on track to be the highest return since the 1950s. Some of those fish will return to Idaho, but just how many remains to be seen.

This year's sockeye return is a rare shot of good news for a fish that has struggled to survive for decades. In 1991, sockeye were the first Idaho salmon listed on the endangered species list.

Officials expected a larger-than-average sockeye run due in part to improved river migration and ocean conditions and more young fish migrating from Idaho, but they could not explain the surprise abundance.

"It's a mystery. This is nothing like what was predicted," said Brian Gorman, spokesman for the NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service.

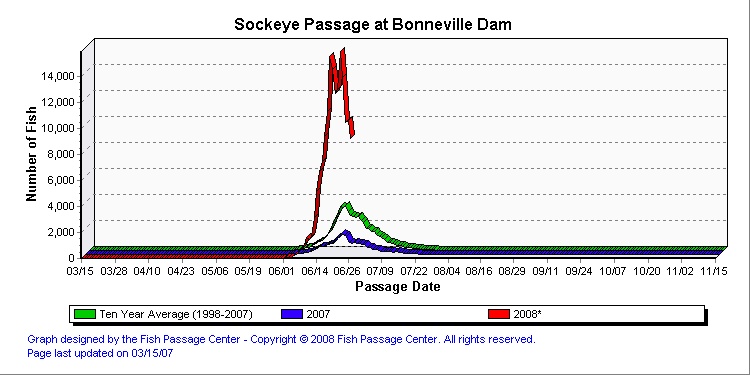

The sockeye count at Bonneville Dam east of Portland was 157,486 fish through Thursday compared with 15,427 at the same time last year. Last year's entire run was 26,700 sockeye at Bonneville Dam.

Officials had originally predicted 75,600 but upgraded it this week to at least 210,000.

"It's never been over 100,000 this early in the year," said Joe Hymer, a Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife biologist.

The largest recorded dam count of Columbia River sockeye was 237,748 fish in 1955. The number has only topped 200,000 twice since counting began at Bonneville in 1938.

The bulk of the Columbia River sockeye run returns to Okanogan and Wenatchee lakes in Washington.

The bulk of the Columbia River sockeye run returns to Okanogan and Wenatchee lakes in Washington.

But modern counts do not reflect the abundance of salmon prior to dam construction on the Columbia and Snake rivers.

The preseason prediction by state and federal biologists was 700 sockeye returning to the Snake River, and that number has not been updated to reflect the larger run.

Biologists don't know if the Snake River component of the run will also be larger than expected.

"We honestly have no idea what's headed our way until they start crossing the Snake River dams," said Mike Peterson, senior research biologist for Idaho Department of Fish and Game's sockeye program.

To reach their traditional spawning waters, Idaho sockeye must swim upstream through eight dams and reservoirs in the Columbia and Snake systems, then all the way to the Salmon River's headwaters, a trip of 900 miles and 6,500 vertical feet. It's the longest salmon migration in North America.

If 700 sockeye reached the Stanley Basin, it would be the most since 1975, which is the first year salmon counting started at Lower Granite Dam.

The record sockeye count at Lower Granite was 531 in 1976.

This year's run would also be larger than the previous nine years combined at Lower Granite.

Three sockeye had crossed Lower Granite Dam as of Thursday, but most of the fish are still in the Columbia. Sockeye typically start reaching Lower Granite in late June, but most return in July.

All sockeye that pass through Lower Granite Dam are headed for the Stanley Basin, but some usually die before reaching their spawning grounds in Redfish Lake.

Over the last decade, about 550 sockeye have crossed Lower Granite Dam, and more than 300 of those reached Stanley.

Fish and Game's Peterson said that in drought years and high temperatures, warm water slows the sockeye migration to Idaho, and some fish don't make it. This year's big snowpack and cold temperatures will mean better migrating conditions, and he expects most sockeye will make it from Lower Granite Dam to Stanley.

"We're expecting pretty good conversion this year," Peterson said.

But the fish still have to make it to Lower Granite Dam. There are currently tribal and sport fisheries on the Columbia that could catch some of the fish bound for Idaho.

The Columbia River management plan allows Indian tribes to catch 5 to 7 percent of the sockeye run, and nontribal sport anglers to catch another 1 percent.

Since 1991, returns have ranged from small to zero. Last year, four fish returned to the Stanley Basin, and only 40 sockeye have returned in the last five years, mainly to Redfish Lake. The lake got its name from the once-abundant sockeye, which turn vivid red before spawning. During the 1955 run, 4,361 fish returned to Stanley.

Sockeye runs have been so small, the state and federal agencies have essentially put the entire population into a captive breeding program - a salmon version of life support to ensure there's enough genetic diversity for them to survive.

In order for sockeye to be removed from the endangered species list, more than 2,000 adult fish would have to return to Stanley for several years.

There's a four-prong strategy for keeping sockeye runs viable, Peterson said.

Hatchery-fertilized eggs are placed in lakes to naturally hatch, and then young fish grow in a natural environment before migrating to the ocean.

Other eggs are hatched in hatcheries, and young fish are raised to 2 or 3 inches long then released into lakes to grow until they're ready for their ocean migration.

Other fish are raised longer in captivity until just before they're ready to migrate, then they're released.

Fish may also be raised to adults, then released into the lakes to naturally spawn.

Peterson said the combined efforts have meant more young fish are produced in Idaho, and he said migration conditions were good in 2006 when this year's return migrated to the ocean. Both contributed to this year's large run of sockeye.

But much of it also remains a head-scratcher. Biologists had expected a large run of spring chinook salmon this year, which came back in smaller than anticipated numbers.

Biologists often credit or blame enigmatic "ocean conditions" for small and large salmon runs. Salmon spend one to four years in the ocean before returning to their native rivers to spawn.

Different species of salmon from different rivers inhabit different parts of the ocean, and many things can happen during their time in the ocean.

"It's part of the remarkable cycle that's not fully understood and over which we have no control," NOAA's Gorman said.

Salmon populations tend to fluctuate wildly, even in natural river systems that have not been altered like the Columbia and Snake rivers have.

But this year's Pacific salmon runs have been a strangely mixed bag.

California and Oregon were considered "disaster areas" because of their abysmal chinook and coho salmon returns, some of which are the lowest on record.

But Alaskan officials are predicting this year's harvest of all salmon species will be above that state's 10-year average.

The sockeye component of Alaska's salmon harvest is predicted at 47 million fish, which is above the 10-year average of 41.5 million.

"We're expecting a pretty typical year," said Laura Fleming, communications director for the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute. "All indicators are for a very good, strong run of sockeye."

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum