forum

library

tutorial

contact

Renewing Idaho's Wild Salmon

and Wild Rivers

by Rocky Barker

Idaho Statesman, July 28, 2014

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Renewing Idaho's Wild Salmon

by Rocky Barker

|

The success and failure of salmon recovery in the Columbia River Basin were on display this month in the Sawtooths.

The success and failure of salmon recovery in the Columbia River Basin were on display this month in the Sawtooths.

Chinook salmon anglers lined up on the Salmon River below the Sawtooth Hatchery on July 19, the final day of the fishing season. Fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, were catching the huge fish that swam almost 900 miles and climbed 6,500 feet to return to the place they were born - which was not the river, but the hatchery.

Meanwhile, 15 miles to the northeast, I walked in a large meadow of tall grass and wildflowers through which Marsh Creek flows. I was on my annual pilgrimage to the place where I began my journey with Pacific salmon in 1990.

I was a little early this year, so it wasn't a surprise that I didn't see any of the long spawners in the 15-foot-wide, gravel-bottomed river.

I first came here with Idaho Department of Fish and Game anadromous fish manager Pete Hassemer and others who were counting the redds, or nests, where salmon lay their eggs. We found a few fish; just 100 chinook salmon spawned that year in Marsh Creek.

My saddest visit was in 1995, when no spring chinook salmon returned. In 2003, I got a glimpse of how Marsh Creek must have looked in its glory days: Parts of the creek were covered with redds - small, cleared-out dips in the gravel dug by female salmon who beat their undersides bloody answering nature's imperative to spawn another generation of chinook.

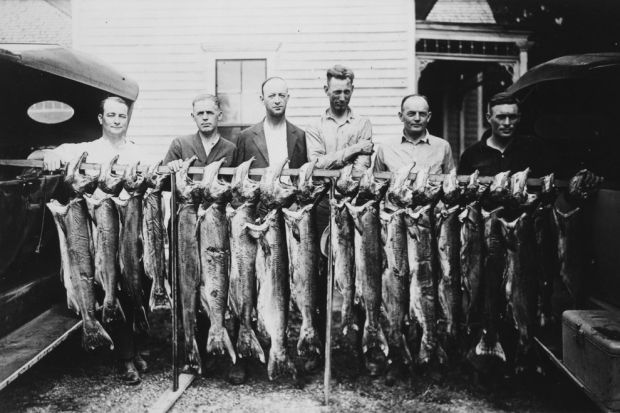

At least 870 chinook spawned in 2003, a number that starts to approach the 1,400 salmon that spawned in 1964. But that year, salmon anglers weren't standing below a hatchery. Many were fishing for wild salmon in places such as Marsh Creek, and their catch totaled 2,944 salmon.

Today, federal fisheries officials say that if annual chinook returns averaged the 870 of 2003, that would be almost enough to take chinook off the threatened species list. But it wouldn't be enough to meet Idaho fishermen's expectations, or return Marsh Creek's meadows to its glory days.

But we don't see returns averaging 2003 numbers. Things got bad again by 2009, when just 167 salmon spawned, reminding us that the bounty of hatchery salmon has not brought us more wild salmon. They have rebounded a bit since, with 411 spawning in 2012.

When salmon advocates filed their latest lawsuit against the federal government's dam and salmon plan for the Columbia and Snake rivers, it didn't make the news. Reporters are waiting to see how the new federal judge handling the case acts on the dam-passage issues that have resulted in a series of losses by the federal government and incremental improvements to keep wild salmon from going extinct.

Will we ever see a plan that puts wild salmon on the road to recovery? No one knows, and even proposals for interim steps and studies prompt political battles.

Anglers, environmentalists, the Nez Perce tribe and the state of Oregon wanted to test whether "spilling" more water over dams instead of through hydroelectric turbines would improve salmon passage and survival. But federal dam and power managers refused, and they had the support of the greenest governor in the nation, Washington Democrat Jay Inslee.

Inslee's top issue is climate change, and he's been convinced that spilling more water means more carbon-based power. He's right in the very short run, but the region needs to know how we will get to recovery as our power system evolves. The spill study, which had the support of an independent advisory council, would provide that.

Inslee's state even threatened to pull out of the Comparative Survival Study program - which gives states and tribes independent science evaluation - to make sure the spill study didn't take place.

Federal fisheries officials say the current salmon and dam program is enough to meet the minimum requirements of the Endangered Species Act. But the recent draft of their recovery plan shows the program is not enough to return to healthy, sustainable salmon populations. To ensure the future of the creatures that are the living manifestation of the wild character of the Pacific Northwest, it will take significantly larger returns of wild salmon.

If spilling more water over the dams won't bring thousands of salmon back to Marsh Creek, that leaves the option of removing the four lower Snake River dams. Will the bureaucrats and politicians find consensus while there's still time? I still dream of one day wading through streams littered with the carcasses of thousands of dead chinook, whose very decay promises renewal of Idaho's wild rivers and Idaho's wild soul.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum