forum

library

tutorial

contact

Better Passage Gets Columbia

River Salmon Past McNary Dam

by George Plaven

East Oregonian, April 17, 2015

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Better Passage Gets Columbia

by George Plaven

|

Lut said the current levels are already enough to PROTECT runs of both adults and juveniles. ...

Salmon advocates and the state of Oregon are suing . . . is still not enough to boost needed RECOVERY

PENDLETON -- An electronic message board keeps track of how much power is generated in real time at McNary Dam east of Umatilla. The sign displayed 479 megawatts Thursday afternoon, or enough electricity for 240,000 homes.

PENDLETON -- An electronic message board keeps track of how much power is generated in real time at McNary Dam east of Umatilla. The sign displayed 479 megawatts Thursday afternoon, or enough electricity for 240,000 homes.

That's good news for residents when they flip on the light switch, but harnessing that energy comes at a cost to native salmon and steelhead. Hydroelectric dams pose an immense barrier across the Columbia River, standing in the way of migratory species as they swim from their natal streams to the Pacific Ocean and back again as adults.

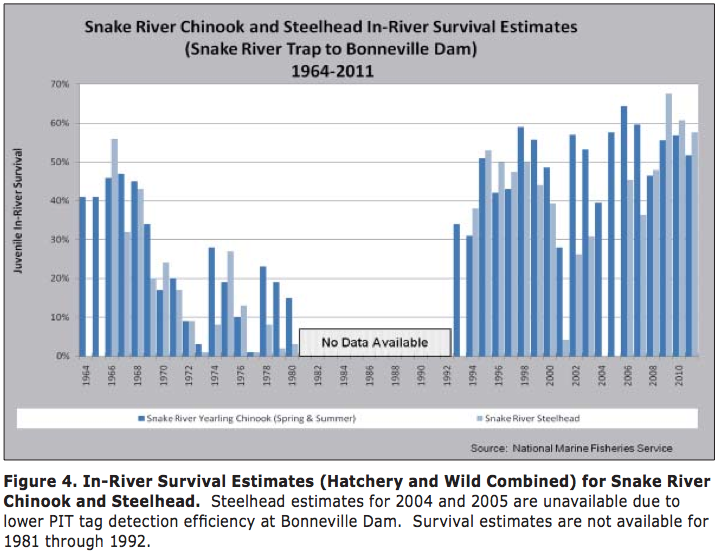

Improving fish passage is a priority at McNary Dam, where federal agencies operating the river's hydro system are required to maintain a 96 percent survival rate for juveniles during springtime and 93 percent over summer. Officials with Bonneville Power Administration and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers say projects completed in recent years are helping them to meet or exceed those targets, and have paid off with huge salmon returns the past two years.

Passage at the dam works both ways, helping young fish move quickly and safely out to sea while also allowing adults back upstream to spawn. "This is a highly rigorous and complex system," said Kevin Wingert, BPA spokesman. "Everything kind of has to be put into balance."

Juvenile fish can make it down past the dam through a couple of different routes, either diving into the spillway, chancing through the generator turbines or screened into a bypass channel that loops all the way around over the Oregon shore and back into the river on the opposite side.

The channel, which is essentially a long winding pipe, was re-routed in 2011 to dump fish a half-mile into the middle of the river, providing better protection from predators. Construction cost between $11 million and $13 million, and includes several transponder, or PIT, tag readers to monitor fish throughout their life cycle.

The majority of fish, however, will pass through the dam's spillway. Spill operations began April 10 at McNary Dam, as more juveniles begin making their long journey toward the Pacific.

Crews at McNary put in weirs at two of the spillway gates in 2007 to allow for passage closer to the surface of the water, where certain species of fish are more likely to approach. Those cost roughly $3.5-$5 million each, said Ann Setter, fish biologist with the Army Corps of Engineers' Walla Walla District.

Crews at McNary put in weirs at two of the spillway gates in 2007 to allow for passage closer to the surface of the water, where certain species of fish are more likely to approach. Those cost roughly $3.5-$5 million each, said Ann Setter, fish biologist with the Army Corps of Engineers' Walla Walla District.

Biologists then conduct a juvenile performance standard test at each of the federal Columbia River dams to gauge survival of the young fish. A 2012 study at McNary found that 83.5 percent of steelhead passed at the spillway and surface weirs, with 99 percent survival. Fourteen percent passed through the bypass channel, with 100 percent survival. A much smaller number of fish -- only 2 percent -- passed down at the turbines, with a predictably lower survival rate of 83 percent.

"Steelhead are always searching for a surface passage route, which these top-spill weirs provide," Setter said.

Roughly 40 percent of the river is spilled at McNary Dam, which is done to maintain adequate passage and limit amount of dissolved gases plunged into the water. If the gas levels are too high, tiny bubbles can get into the scales of juveniles and cause them stress, or even death.

Too much spill is also discombobulating to adult fish as they try to find their way upstream to one of McNary's two fish ladders, said Agnes Lut, fish biologist with BPA. Though some environmental groups would like to see more spill at the dams, Lut said the current levels are already enough to protect runs of both adults and juveniles.

"We could have so much water coming through the dam that these adults just stop and don't know where the ladder is," Lut said. "That can increase their predation rate."

Their claim, she said, is backed by steadily rising adult salmon returns. More than 1 million fall chinook made it back into the Columbia last year, and fishery managers are expecting 925,000 for the 2015 season.

Salmon advocates and the state of Oregon are suing the federal agencies, arguing the way they run the Columbia River hydro system is still not enough to boost needed recovery for threatened and endangered fish species. A hearing is scheduled for June 23 in Portland.

Wingert said they are always on the lookout for new ways and practices that can help them better protect fish at the dams.

"We have an obligation to mitigate for continued operation of the dams," he said. "Fish considerations come first to the table."

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum