forum

library

tutorial

contact

Sun Power: As Oregon Soaks

Up Solar Power, Farmland Shrinks

by Kyle Odegard

Capital Press, August 1, 2024

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Sun Power: As Oregon Soaks

by Kyle Odegard

|

Utility scale, ground-based solar array costs about $1 per watt,

commercial rooftop systems cost nearly $2, residential projects $3.25 per watt.

ASHLAND, Ore. -- It's always sunny in Ashland, at least when it comes to solar power.

ASHLAND, Ore. -- It's always sunny in Ashland, at least when it comes to solar power.

Rooftops shine like obsidian in new subdivisions, and Southern Oregon University is installing solar arrays with hopes of running on renewable energy.

Solar power accounts for 8 million kilowatt-hours of electricity every year here, or about 5% of the total power used in Ashland, which has a population of 21,500.

"Ashland has been a pioneer in solar for decades," said Rob Del Mar, Oregon Department of Energy senior policy analyst.

About 30 years ago, Ashland voters approved an added utility charge for solar projects.

"We have a population that has goals for climate protection, so we have a higher adoption rate than a lot of other urban areas," said Larry Giardina, city of Ashland Conservation Division analyst.

The city operates its electric utility, too.

"Most places, utilities try to stop solar because it's competition," said Jeff Sharpe, founder and COO of Stracker Solar, a local technology firm that builds solar panels that sweep and tilt to track the sun.

Roughly 850, or 6.6%, of the city's 12,800 electric accounts produce solar power. About 150 new solar customers are added every year. Giardina expects that pace to continue as technological advancements make solar panels more efficient and less expensive.

Urban potential, rural reality

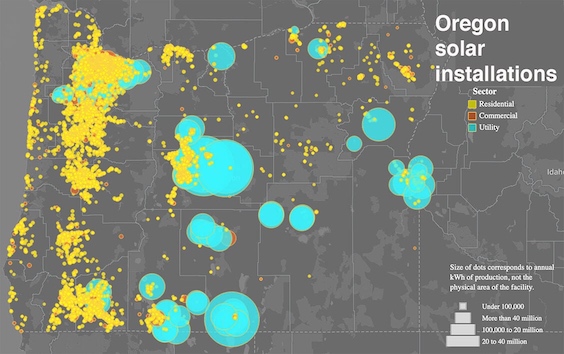

Oregon cities have immense solar energy potential on rooftops and parking lots, but the bulk of the state's solar power comes from massive ground-based projects in the country. Many projects are planted on farms and ranches.

Experts said that's unlikely to change, despite success stories like Ashland and steps that could reduce the price of solar panels for urban residents and businesses.

Solar projects on rural land cost far less due to factors such as lower acquisition or lease prices, ease of development and economy of scale.

While solar is a renewable power source, the Pacific Northwest already has relatively low electricity rates thanks to another renewable power source -- the region's many dams that produce hydropower.

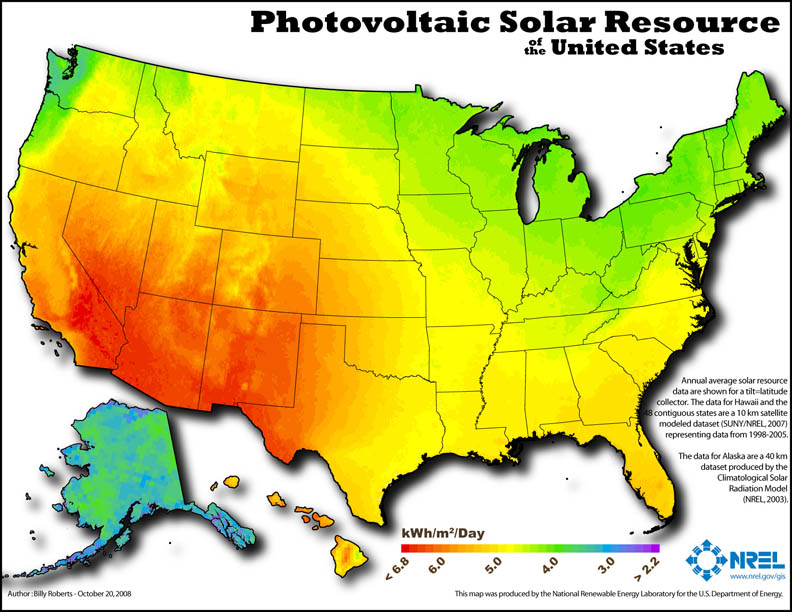

Then there's the climate of the Willamette Valley, Oregon's population center. The sun shines enough on Portland and the coast to make solar power feasible, but there are fewer cloudy days east of the Cascade Range and in Southern Oregon.

The state has a goal of preserving farmland, but that's at odds with its lofty goals for climate and clean energy.

Even so, more rural areas will include solar arrays, and that worries farmers.

"Throughout the past few years, we have seen agricultural lands looked to for industrial uses, housing, and renewable energy. Simply put, if all of these needs are met by converting agricultural lands, how much land is left to farm?" said Lauren Poor, Oregon Farm Bureau vice president of government and legal affairs.

The bureau continues to oppose solar facilities on productive agricultural lands when alternative sites are available, Poor added.

Loss of farmland

Plenty of farm acreage has already disappeared.

From 2011 to 2021, 25,276 acres of farmland were converted to solar projects, according to an Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development report.

At the time of the report, the state had six projects under review that would cover 24,000 additional acres of farmland.

Projects currently under review will triple solar power generation, according to the Oregon Department of Energy.

"We're at the early end of this visibility," said Tucker Ruberti of SOLV Energy, a company that builds solar projects.

"In the next five years, we will see almost a 10x growth in total solar generation in Oregon. And it will be 90% with these large rural projects," added Ruberti, who is also an instructor at Oregon State University-Cascades in Bend.

He noted that doesn't mean 10 times the land use, and most projects will be in Eastern Oregon on ag land that isn't high value.

One current proposal is the Sunstone Solar Project in Morrow County, which could power 200,000 homes.

The solar farm would be on 9,442 acres of exclusive farm use land. About 1,280 acres would be covered with solar arrays, and the rest of the land would be for other structures, roads, fencing and transmission lines.

Agency staff recommended site approval and the public can comment until an Aug. 22 hearing.

Oregon solar power output

Solar projects in Oregon generated about 1.97 million megawatt-hours in 2022. Roughly 85% of that came from large utility projects. The 10 largest solar farms delivered about 34% of the state's total.

Solar projects in Oregon generated about 1.97 million megawatt-hours in 2022. Roughly 85% of that came from large utility projects. The 10 largest solar farms delivered about 34% of the state's total.

Residential projects contributed nearly 8% and commercial projects about 7%.

In 2012, the state's total solar production was 6,400 megawatt-hours.

Del Mar, of the state Department of Energy, said the state's energy use peaks in the summer and winter.

"There's a clear and complementary value in solar with the summer peak. In the winter, there are other ways to address peak power use, such as wind and hydropower," he said.

In 2023, utility scale solar power generated about 3.2% of Oregon's energy production, while wind turbines generated 14.7%, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Lower costs at ground level

A utility scale, ground-based solar array costs about $1 per watt, while commercial rooftop systems cost nearly $2 and residential projects $3.25 per watt, Ruberti said.

Rooftop solar is more expensive due to labor and permitting, as sites generally need to be custom engineered. Customer acquisition also increases prices.

Ruberti believes costs can drop through a more efficient process.

For example, Germany has become a solar leader with installations that cost half as much as those in the U.S.

Paul Israel, founder and president of Sunlight Solar in Bend, said integration and standardization of application software would streamline the process and reduce costs.

A hard sell for commercial

Solar remains a hard sell for businesses because financial benefits aren't great, even with a 30% federal installation rebate and depreciation on taxes.

"The energy costs are so low here that it's very hard, even with grants and other economic supports, to make it less expensive than buying energy from the grid," Ruberti said.

Still, across the country, a huge number of Target and Walmart stores already have solar panels on rooftops. Walmart is among the top private solar energy producers in the nation. Panels are being installed regularly above parking lots in California, Arizona and Nevada.

Solar panels in parking lots cost more than rooftop installations because structures need to be built to hold the arrays.

Del Mar expects to see more parking lot arrays as prices drop. He also believes businesses could incorporate electric vehicle charging stations.

Rethinking solar

Ruberti said community solar projects may have more promise than commercial operations.

"There's more and more community solar in Oregon," he added.

In Ashland, the city covered a 75-yard-long parking structure with panels in 2008 and sold shares to residents. That generates about 500 kWh of electricity every year.

Giardina said companies in Ashland also could lease rooftop space to cooperatives, and that might make solar power more feasible.

The city is leasing one of its roofs to a cooperative for a planned solar project.

Cost savings for residents

Experts said residents who install solar panels can generally make their money back in seven to 10 years, and systems are typically warrantied for 25 years.

Sunlight Solar specializes in installing solar systems for families and small farms, and the average system for the business has a capacity of about 10,000 watts. Israel, the founder, said that would cost between $28,000 to $35,000 to install.

The rising price of power is a factor in purchasing solar panels, he said. "The higher it is, the better the payback" for solar, Israel added.

Charging electric vehicles with photovoltaics makes the economics better, as solar power is cheaper than gasoline, experts say. The financial equations -- for businesses and residents -- will also improve with time, they say.

The reason: The cost of solar power equipment has dropped 90% in the past decade, Ruberti said.

Other solar benefits

Saving money isn't the sole purpose of solar power, Israel said.

"Do I want resiliency? Do I want to be more independent? Do I want to make an impact on global warming?" he said.

When the grid goes down, solar installations paired with batteries can act as independent power systems, Del Mar said. Microgrids could cover a home or entire city blocks.

Public safety agencies can use solar power to complement or replace diesel generators during emergencies, Del Mar said.

Ashland's newest project

Ashland's latest solar project was installed earlier this year with resiliency in mind.

Made by Stracker, six dual axis solar arrays sit 20 feet tall on metal posts and follow the sun.

The system provides extra electricity and battery capacity, and the grid they're tied to fast-charges the city's fleet of vehicles, resulting in fuel savings.

Sharpe, Stracker's founder, said the project was funded through a $940,000 grant from the Oregon Department of Energy.

With its design, Stracker works well for dual use projects. The panels have enough clearance for farm vehicles, crops and livestock but the posts have only a 2-by-2-foot footprint.

"We can fill up any parking lot, we can fill up farmland, and still have the land be usable," said Eric Wolff, Stracker vice president of operations.

Muddy Creek project

For more than a year, the Friends of Gap Road have opposed the Muddy Creek Energy Park, planned for nearly 1,600 acres near Brownsville, Ore. The project sponsors aim to graze sheep underneath solar panels.

Most farmers don't have an issue with solar power and small arrays, said Dave Rogers, a farmer and spokesman for the group.

"We feel that industrial-sized energy projects should never be allowed on farmland or ranchland," Rogers said.

"There are no successful large solar projects on farmland that don't just remove the land from farming long term," he added.

Land use rules

Rogers criticized current rules that allow large solar projects to bypass Oregon's usual land use planning process and apply directly to the Oregon Department of Energy Facility Siting Council.

Applicants can ask for exceptions to disregard size restrictions and ignore the state's goal of preserving agricultural land.

In a 2018 resolution, the state Board of Agriculture supported more protection of valuable farmland and sought the evaluation and reconsideration of the existing land use regulation.

The state Department of Land Conservation and Development is discussing the issue, and new rules could be adopted by next summer.

Sharpe said he expected legislation to promote agrivoltaic projects that allow grazing and other agricultural uses instead of ground-based solar "that fences off acres of farmland."

"It costs a little more to install, but then you get dual use out of it," Ruberti said.

Rogers said the rules need to change, in part because there are better areas for solar.

"There is no reason to destroy farmland and ranchland," he said.

Urban possibilities

Giardina supports rooftop or elevated arrays even in cities to preserve the best use for land.

In the near future, local solar power could account for 30% of Ashland's electricity, Giardina estimated.

That might not sound like a lot, but it shows what's possible in urban environments. And none of the megawatt-hours generated in cities are coming from farmland, Del Mar said.

"There's a lot of room for growth," Giardina said. "We have unshaded rooftops all over town."

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum