forum

library

tutorial

contact

Can Federal Dam Operators

Save Northwest Salmon?

by Rocky Barker

Idaho Statesman, November 26, 2016

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Can Federal Dam Operators

by Rocky Barker

|

Anglers are lining the banks of the Boise River this weekend after the Idaho Department of Fish and Game released the last 250 steelhead of the season Wednesday.

Anglers are lining the banks of the Boise River this weekend after the Idaho Department of Fish and Game released the last 250 steelhead of the season Wednesday.

The steelhead were raised in the Rapid River Hatchery near Riggins, left as juveniles to migrate down the Salmon River, the Snake River and the Columbia River, where they encountered eight dams and reservoirs on their way to the Pacific Ocean. Two and three years later, those fish that survive their odyssey to and through the Pacific returned up the Columbia, Snake and back to Idaho.

Historically, steelhead and chinook salmon made the trip naturally back to the Boise River, but irrigation diversions and dams downstream blocked the fish from the Boise and other Snake River tributaries. By 1990, Idahoans had nearly given up on salmon.

"I started guiding on the Salmon River in 1987, and you could go three days without seeing a fish," said Gary Lane, a Riggins outfitter.

The listing of salmon and steelhead in the Snake River as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act in the early 1990s forced management changes throughout the Columbia River Basin. And as the cyclical productivity of the Pacific Ocean got better, salmon returns improved, especially for fish raised in hatcheries.

This year, more than 2.5 million salmon returned to Bonneville Dam, near Portland, the closest one to the ocean. More than 100,000 chinook made the trip up the Columbia and Snake rivers to Lower Granite Dam west of Pullman, Wash. That's about the 10-year average for salmon numbers, although steelhead returns were half of the previous year's.

Biologists and oceanographers say unusually warm conditions in the Pacific may be the cause of the steelhead dropoff and could portend reduced returns of all salmon in coming years. These warm conditions combined with dam passage are especially hard on the wild salmon and steelhead that spawn in tributaries of the Snake, Salmon and Clearwater rivers and are the seed corn of the region's bounty.

Idaho Fish and Game biologists are seeing a sharp drop in the number of jack salmon, those that return from the Pacific after only a year. That's a good indicator of likely returns next year for the larger class of two-year salmon. For one-year steelhead, the returns are even worse.

"They're almost nonexistent," said Peter Hassemer, Idaho Fish and Game's salmon and steelhead manager.

Good ocean conditions, improved measures at the dam and several years of improving river flows have restored great fishing opportunities for hatchery salmon over the past two decades. But wild salmon have not shown a trend toward recovering to a sustainable and healthy population. And with Pacific Ocean conditions worsening, Hassemer is worried.

"We can't always rely on ocean productivity to recover these fish," he said.

WRITING A NEW PLAN

The three federal agencies that operate and market power from the 14 federal Columbia and Snake River dams are beginning a five-year environmental review of the entire system. The agencies are holding a series of open houses across the Pacific Northwest to ask the public what needs to be considered as federal officials make decisions.

All of this came about because of a series of lawsuits and judicial orders calling on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation, which operate the dams, and the Bonneville Power Administration, which sells the power, to do more to help the salmon, the living embodiment of the wild character of the Pacific Northwest.

These 14 dams provide 65 percent of the electricity used by the more than 9 million residents who live in the Columbia watershed, an area greater than the size of France. The dams remain critical to the $640 billion economy of agriculture, food processing, high technology and even shipping as far inland as Lewiston.

Salmon and steelhead provide millions in economic benefits to fishing-related businesses and spiritual sustenance to the region's Indian tribes. The reservoirs behind the dams offer recreation to thousands of boaters, anglers, swimmers and campers throughout the Northwest.

To restore fish numbers to sustainable levels across the Northwest, it will take even more sacrifice by the region's residents, U.S. District Judge Michael Simon said in a sweeping ruling in May that ordered the federal agencies to go back to the drawing board on a plan to manage dams, generate power and protect fish.

Simon is the latest of three federal judges over two decades who have rejected five consecutive federal plans to manage the Columbia and Snake dams since salmon and steelhead were listed as threatened and endangered.

"The (federal Columbia River power system) remains a system that ‘cries out' for a new approach," Simon wrote.

BUT HOW TO DO IT?

He's not the only one telling the agencies they need to do more if they hope to recover salmon and steelhead in the Columbia and Snake, especially in light of a changing climate that is affecting mountain snowpacks, river temperatures, migration seasons and even ocean conditions. In 2015, nearly all of the returning Snake River sockeye that spawn in the Sawtooth Basin died in the warmer waters of the Columbia and its tributaries. Cooler weather and more careful river management prevented a repeat in 2016.

The National Marine Fisheries Service, also know as NOAA Fisheries, just issued a draft recovery plan for Snake River spring and summer chinook. The plan, which largely depends on voluntary actions by federal agencies, states, Indian tribes, industry and landowners, concludes that salmon productivity has to be improved beyond what is being done today.

Ritchie Graves, the NOAA Fisheries biologist who oversees hydropower, said it will take a comprehensive approach that includes controlling fish predators such as birds, seals and otters, and improving estuary habitat. But it also will take more work on the dams, which he hopes this new review process brings.

"The one thing that kind of stands out is that Judge Simon expects the Corps of Engineers is going to come up with some action that is going to improve the productivity of salmon and steelhead," Graves said.

Specifically, Simon told the agencies the review needed to consider breaching the four dams on the lower Snake River in Washington state: Lower Granite, Little Goose, Lower Monumental and Ice Harbor. For nearly 20 years, a consensus of fisheries biologists has said removing the four dams would remove obstacles and improve river flow and fish passage enough to recover wild Snake River salmon and steelhead.

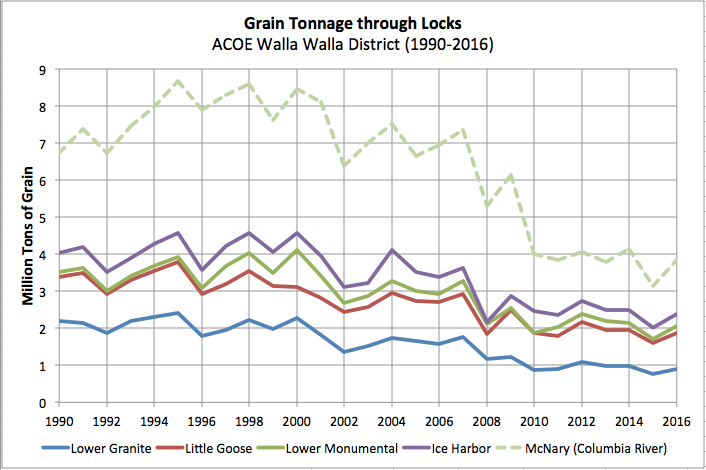

The dams produce more than 1,000 annual megawatts of electricity and have the capacity to produce electricity within minutes to respond to peaking demands and to balance use across the region's power grid. And even though shipping on the Snake River has dropped steadily over the past 20 years, 10 percent of the nation's wheat is still barged to market from ports in Idaho and Washington.

NEW IDEAS?

NEW IDEAS?

"The facts and analyses that have been done -- exhaustively -- over many years simply haven't supported removal of the dams from a climate change, salmon restoration or economic perspective.," said Terry Flores, Executive Director of Northwest River Partners, an alliance of farmers, utilities, ports, and large and small businesses.

Jim Waddell, an economist who retired from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, worked for the Corps' Walla Walla office when it did the last full environmental review of the dams that concluded the benefits of breaching the dams were not as great as taking lesser measures for fish and keeping the dams intact economically. But it did suggest that breaching might be the best way to recover salmon and steelhead.

He thought then that the agency overestimated the hydropower benefits and later learned it underestimated the recreation benefits from breaching. He has spent the past two years asking the Army and the Obama administration to order the dams breached. He cites the 2001 review that directed the federal agencies to make minor changes in operations and spend millions on habitat, hatcheries, and commercial and sport fishing improvements. If the fish were not recovered, Waddell says, the Corps was to begin the work necessary to breach the four dams.

"Why are we going another five years and spending millions of dollars when we already have an (environmental impact statement) with breaching in it?" Waddell said.

Lori Bodi is Bonneville Power's vice president of environment, fish and wildlife. She has worked at NOAA Fisheries and even at American Rivers, one of the national environmental groups that endorsed dam breaching.

She acknowledged that Simon's order is a cry for a new approach to the salmon and dam issue, which has been a major part of her career for a quarter-century. The agencies are looking at all options, she said: breaching, spilling more water over the dams to improve fish migration, installing fish-friendly turbines, and other ideas.

The open houses and calls for comments the agencies are undertaking are another way to get new ideas, she said.

"In a way, the litigation has had a positive effect in that it has taken us to that higher level of fish passage than before," Bodi said. "No one is saying we're done."

Video Link:

Opinions Gathered at Boise Meeting on Dam Salmon Issues, by Staff at the Idaho Statemsan.

A Boise steelhead angler's view on dams, by Staff at the Idaho Statemsan.

OPEN HOUSE TUESDAY The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Bonneville Power Administration and Bureau of Reclamation will hold an open house on the environmental review of operations of the Snake and Columbia river dams on Tuesday from 4 to 7 p.m. at Boise's Grove Hotel. Submit written comments at www.crso.infoWHAT DOES THIS REVIEW MEAN FOR...

... Idaho anglers? The more done to improve wild salmon, the more fishing opportunity; hatchery fish will benefit, but it could mean changes in harvest regulations. Eventually wild fish could replace hatchery fish as a target for anglers. The recent recovery plan for Snake River spring and summer chinook makes it clear that current measures are not enough to recover the populations. Biologists say removing one or more dams is one answer; spilling more water over the dams away from hydroturbines might be another.

... Idaho farmers and other water users? The Nez Perce Water Rights Agreement of 2004 assured that water from the Boise River reservoirs, the Payette and the upper Snake River would continue to flow downriver to aid fish migration, which a federal judge said was adequate to meet the Endangered Species Act. So that means Idaho dams and irrigation systems are not part of the review. But the Idaho Water Users Association is urging its members to stay involved and comment.

... Idaho Power? The utility that provides most of us in Southwest Idaho with electricity is not included in the review, but it still is seeking to relicense its Hells Canyon hydroelectric dam complex on the Snake, which is expected to cost hundreds of millions by the time its done. And Idaho Power does sell electricity, and if the Boardman to Hemingway High Transmission line is built, it could get even more, so indirectly Idaho Power and Idaho customers have a stake in the outcome of the debate.

... tribal interests? The Nez Perce was among the groups that sued and won, resulting in a judge's ruling to do more for fish. The tribe support dam breaching. The Shoshone-Paiute and the Shoshone Bannock tribes want more improvements.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum