forum

library

tutorial

contact

Idaho Chinook, Steelhead

in Trouble

by Colin Tiernan

Twin Falls Times-News, November 7, 2019

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Idaho Chinook, Steelhead

by Colin Tiernan

|

TWIN FALLS -- Idaho salmon and steelhead are in trouble. Several years of warm ocean temperatures are a big reason why alarmingly few smolts have made it back to the Gem State as adults since 2015.

TWIN FALLS -- Idaho salmon and steelhead are in trouble. Several years of warm ocean temperatures are a big reason why alarmingly few smolts have made it back to the Gem State as adults since 2015.

Idaho Fish and Game Wild Salmon and Steelhead Program Coordinator Tim Copeland said warm oceans aren't good for chinook salmon and steelhead survival rates. Until a few years ago, the species were doing relatively well.

"When you're working with salmon and steelhead, you kind of have to take what the ocean gives you," Copeland told the Times-News.

Copeland was one of a handful of salmon and steelhead experts who spoke before Gov. Brad Little's salmon and steelhead workgroup in Twin Falls recently. The workgroup aims to provide the governor's office with recommendations for revitalizing threatened and endangered fish populations and includes members representing hydroelectric power, environmental groups, agriculture, tribes and sportsmen.

Idaho Conservation League Executive Director Justin Hayes is a member of the workgroup. He said that he feels good about the collaborative process, but emphasized the situation is dire.

"(These species) are going extinct, and, at this rate, will be gone in our generation," Hayes said.

Very few fish

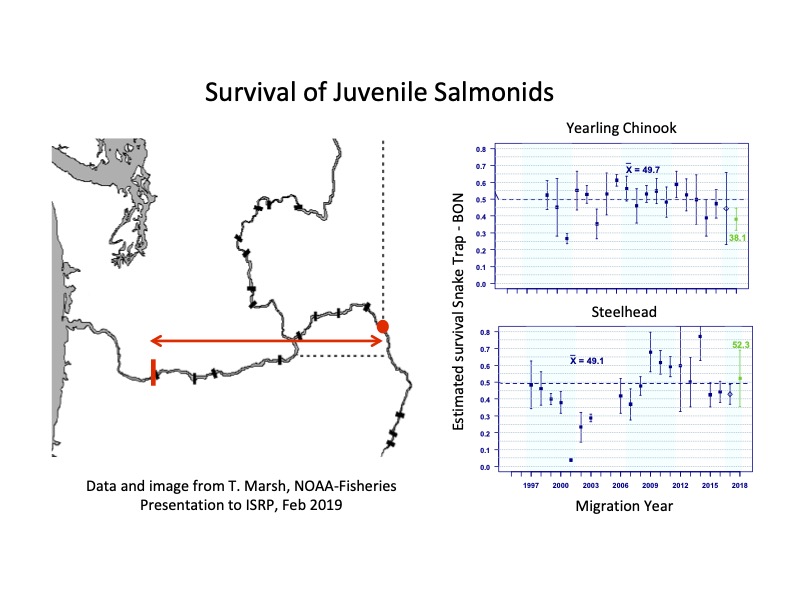

Dams are the main reason that Idaho's salmon and steelhead populations are struggling. Idaho salmon and steelhead face a perilous 800-mile journey to the ocean, then another 800-mile return trip.

But the recent drop in fish numbers is specifically the result of unprecedented warm ocean conditions. Salmon and steelhead put on about 98% of their body weight in the ocean, so when those habitats are disrupted, the fish suffer.

The ocean "is where salmon become salmon," Copeland said.

Sea lions have also impacted salmon and steelhead numbers.

Ritchie Graves, the chief for the Columbia basin hydropower branch at National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration fisheries interior Columbia basin office, said that 15 years ago, sea lions and other pinnipeds weren't that much of an issue. Now they eat between 15% and 35% of the salmon and steelhead that make it past the Bonneville Dam on their way to the mouth of the Columbia River.

Combinations of long-term dam impacts and changing environmental conditions have dramatically reduced the number of salmon and steelhead that make it back to Idaho. For instance, only 17 sockeye salmon made it back to the Stanley area this year.

"We're lucky they're still with us," Copeland said of sockeye.

But chinook salmon and steelhead aren't faring too much better.

"Depending on the species, we are at 10-25% of what the recent average has been in the last few years," Copeland said.

Salmon and steelhead populations have always been cyclical, oscillating between strong and weak years. The problem is when the species experience too many down years in a row.

"Since 2014, 2015 it's been a constant downhill slide," Copeland said.

It's not just wild fish that are hurting.

"There's a lot of focus on wild fish, but our hatchery fish are also spiraling toward extinction," Hayes said.

Last year, 15,000 of the 5 million steelhead raised in the Magic Valley returned to Idaho.

Salmon and steelhead that return to the Stanley area -- which is about as far east as they go -- are some of the toughest fish in the world, climbing 7,000 feet in elevation to reach their spawning grounds. Historically, about half of the salmon and steelhead throughout the Columbia basin start their lives in Idaho, Copeland said.

The four Hs

There are four broad areas of focus when talking about reviving Idaho's struggling fish: hydroelectric power, habitat, harvesting and hatcheries.

Rehabbing habitat is a long-term way to help grow fish numbers. That can entail cleaning up streams and riverbeds or planting trees in order to provide shade and cool down water temperatures in spawning grounds.

The best near-term way to help fish is by either removing dams or making it easier for fish to clear the dams safely.

Between 80% and 90% of fish survive any given trip through turbines. But Idaho fish have to make it past eight dams, potentially eight sets of turbines. That's more turbines than Oregon or Washington fish face. The losses add up.

There's data suggesting that increasing the amount of water in rivers can increase fish survival rates, Copeland said. Speeding up rivers helps the fish.

"The quicker you can get Idaho fish to the ocean, the more likely they are to be successful," Copeland said.

There are a number of ways to make dams safer for fish. You can reduce the amount of water passing through the turbines and increase the amount that spills over the dams. But the best way to help fish is to remove the dams altogether. Rep. Mike Simpson (R-Idaho) has raised the idea of breaching some dams to ensure that Idaho doesn't lose all its salmon and steelhead.

Hayes thinks dam removal has to be part of the recovery conversation.

"We think that, ultimately, dam removal is necessary as part of the collection of strategies to restore our fish to harvestable and abundant numbers," he said.

The current approach for salmon and steelhead recovery isn't working in Hayes' opinion. He also noted that the Magic Valley is paying some of the costs of recovery efforts by using less water for ag purposes, but isn't seeing any returns. Magic Valley efforts aren't leading to more fish returning to central Idaho.

Copeland said he thinks public opinion has a big role to play in saving these fish.

"A lot of this has to do with people caring," he said. "The more people that know, the more people that care, the more likely that good things are going to happen."

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum