forum

library

tutorial

contact

Hatching Reform

by Rebecca ClarrenHigh Country News, June 10, 2002

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Hatching Reformby Rebecca ClarrenHigh Country News, June 10, 2002 |

SEATTLE, Wash. -- From 80 feet above downtown, the throngs of people wrapped in raincoats on the sidewalk below look like a spilled package of multicolored candies. The view is less colorful looking outward from the eighth floor window of the historic Cobb building, but no less busy; glass and steel high-rises thrust upward in every direction. Except to the west. There, cranes and warehouses and smokestacks meet the silver waters of Puget Sound. It's hard to imagine, but somewhere out there, just beyond the urban shore, schools of salmon still swim swiftly to and from the Pacific Ocean, as they have for thousands of years.

SEATTLE, Wash. -- From 80 feet above downtown, the throngs of people wrapped in raincoats on the sidewalk below look like a spilled package of multicolored candies. The view is less colorful looking outward from the eighth floor window of the historic Cobb building, but no less busy; glass and steel high-rises thrust upward in every direction. Except to the west. There, cranes and warehouses and smokestacks meet the silver waters of Puget Sound. It's hard to imagine, but somewhere out there, just beyond the urban shore, schools of salmon still swim swiftly to and from the Pacific Ocean, as they have for thousands of years.

On the streets below, salmon kitsch is everywhere. Tourists traipsing this downtown area can buy salmon-engraved shot glasses, potholders shaped like chinook, and even salmon-shaped flashlights - squeeze the rubber fins and a light pops out the mouth. While images of the fish are ubiquitous, wild salmon (and steelhead, which fish biologists now classify with salmon) populations have never been so depressed. The federal government has listed 15 runs of Northwest salmon as threatened or endangered, yet in most cases they barely trickle. In many streams, a hungry otter or sea lion could wipe out an entire population of fish.

Here, above an ever-expanding sea of concrete and humanity, the idea of salmon recovery seems laughable. Yet in this small office, a no-nonsense conservation group called Long Live the Kings is working to bring wild stocks back to the Northwest. They aren't doing anything sexy: There's no talk of tearing down dams, ripping up roads or filing lawsuits against ranchers to keep cows out of streams. Instead, the group has tackled the mundane business of reforming Washington's hatcheries - those concrete fish-ponds where huge numbers of salmon are artificially spawned and reared for release in the wild.

It's an enormous task; Puget Sound and Coastal Washington alone have nearly 100 hatcheries, the largest concentration in the world. These hatcheries are designed to take the place of the salmon's natural breeding grounds: wild rivers. And the numbers are impressive. Managed by an assortment of state, federal, private and tribal groups, hatcheries produce an estimated 300 million fish every year.

So why should such productive enterprises be reformed? Because, as in so many instances where humans have inserted themselves into the affairs of wild creatures, numbers tell only a small portion of the story.

Ever since the first West Coast hatchery was built in California 130 years ago, hatcheries have served as a tool to perpetuate the all-American assumption that we can clear-cut forests, overgraze watersheds and dam rivers, and still have abundant salmon. Managers can do with a strip of glorified lap pools what it took nature a chunk of a continent to accomplish. Society has clung so dearly to that myth that it has ignored nearly a century of warnings. Some scientists say hatcheries are ineffective at best, and at worst, they may destroy wild salmon runs by spreading disease, watering down the gene pool and - perhaps most serious of all - serving as a convenient excuse not to deal with the real threat: inhospitable rivers.

It's a situation that has frustrated fish advocates to the point where some have called for the end of hatcheries. Yet the leaders of Long Live the Kings believe there is a middle road where both fish hatcheries and wild recovery are possible. Working with independent scientists and state, federal and tribal leaders, the group wants to use hatcheries not only to churn out oodles of fish for fishermen, but to produce fish that are almost indistinguishable from their wild brethren, fish that will serve as a repository for salmon genes until society develops the will to restore the rivers and ocean.

"We wanted to escape the religious debate of whether hatcheries are good or evil," says Barbara Cairns, director of Long Live the Kings, "With the (human) population expected to double in the next 25 years, we recognize that hatcheries will be here. As desperate pragmatists, we wanted to ask a different question - could we use hatcheries to help recover natural populations?"

Concrete habitat

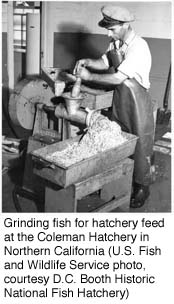

The whoosh of traffic on Interstate 84 is the steady soundtrack playing at Oregon's Bonneville Hatchery. Sandwiched between the highway and the Columbia River, this expanse of concrete pools, lined up like tire tracks left by a Mack truck, houses tens of thousands of baby salmon. Nearly a century old, Bonneville produces 10 million salmon smolts annually. A federal employee wearing green waders walks the runways between the tanks tossing reddish pellets from a bright blue bucket. As the dusty substance hits the water, the surface boils with hungry fish mouths.

It is this very act of feeding that riles critics. By top-feeding the young fish, managers are unintentionally training them to swim to the surface, says Andre Talbot, a geneticist for the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. When released into the wild after about a year of captivity, they will be easy prey for birds and fishermen, he says, quite unlike wild fish, which feed from the relative safety of the river bottom.

It is this very act of feeding that riles critics. By top-feeding the young fish, managers are unintentionally training them to swim to the surface, says Andre Talbot, a geneticist for the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. When released into the wild after about a year of captivity, they will be easy prey for birds and fishermen, he says, quite unlike wild fish, which feed from the relative safety of the river bottom.

"This is like raising your children in the basement for 14 years and then kicking them out and telling them to go get a job," says Talbot. "These hatcheries are very good at producing lots of fish, but they don't do anything to help the natural ecosystems."

The problems created by traditional hatcheries are numerous: Crowded hatchery tanks are breeding grounds for bacterial diseases, which later can spread to wild populations; after release, hatchery fish compete with wild fish for food and cover; and after several years in the ocean, the few surviving adults return to the hatchery tank where they were raised, robbing the river of the vital nutrients in their carcasses.

"These hatcheries are only concerned with producing fishing opportunities," says Talbot. "These fish are treated like a commercial product. They're not treated like a natural resource."

Wild fish, though, were very much on the minds of the builders of Bonneville Hatchery and other early hatcheries. It was erratic and declining runs of wild salmon - caused by over-fishing, the deterioration of the salmon's inland habitat from logging, mining, livestock grazing and farming, and the vagaries of the weather - that spawned the Northwest's hatchery era in the late 1800s.

"All civilized governments in the world (should) foster the science of fish culture," George B. Goode, a U.S. Fish Commission administrator, wrote in 1882. Hatcheries, he continued, were the only way "to bring back the number of salmon to what it was when nature was supreme."

The ability of managers to produce huge volumes of fish seemed a vast improvement over nature. In the wild, salmon lay eggs beneath the river's gravel bottom in nests called redds. The eggs can be stranded on dry banks as river levels drop, eaten by other creatures, crushed by elk or cattle, or silted in by runoff from clear-cuts and dirt roads. Using hatcheries, fish culturists could artificially spawn the parent fish, house the redds in the safety of incubators, and almost without fail, turn the eggs from a relatively small number of fish into an enormous new generation.

Facilities like the Bonneville Hatchery were clearinghouses for fish eggs from as far away as Idaho and southern Oregon. The progeny were released into rivers throughout the region - although rarely were the fish returned to their native streams. Early hatchery managers didn't understand that each river and stream has its own unique subspecies of salmon, highly adapted to site-specific flow regimes, habitat constraints and diseases.

"Very few, if any, of these fish survived; it was probably a wasted effort," writes Jim Lichatowich in Salmon Without Rivers, a searing critique of hatchery management. Published three years ago, his book recounts the ways that hatchery policy has stumbled and fallen, time and again.

"The more I looked into the history of hatcheries, the more disturbed I became," he says, staring out a window in what he calls, "the best office in the world." Beyond the blooming cherry trees that line his garden, the Columbia River rolls quietly past Columbia City, a small town north of Portland.

Lichatowich has had plenty of exposure to hatcheries in a 30-year career as a fish biologist; he has worked for state agencies in Oregon, tribes in Washington and as a consultant in both states. Over time, he became convinced that hatcheries were not only churning out doomed fish, but that they were hurting wild salmon. He discovered that he wasn't the first critic.

Lichatowich has had plenty of exposure to hatcheries in a 30-year career as a fish biologist; he has worked for state agencies in Oregon, tribes in Washington and as a consultant in both states. Over time, he became convinced that hatcheries were not only churning out doomed fish, but that they were hurting wild salmon. He discovered that he wasn't the first critic.

As early as 1928, Elmer Higgins, a head scientist at the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries (the precursor to the National Marine Fisheries Service) announced to a crowded room of Fisheries' scientists that, "despite 55 years of artificial propagation, the Pacific salmon fishery has declined alarmingly." He and his supervisor called for more research, but though the findings of two subsequent studies called the hatchery program into question, nothing changed.

Despite such concerns, when the federal government wanted to pepper the Northwest with hydropower dams, it deemed hatcheries a convenient surrogate for habitat. Politically, there was no contest between cheap power and salmon.

"It is, therefore, the conclusion of all concerned that the overall benefits to the Pacific Northwest from a thoroughgoing development of the Snake and Columbia are such that the present salmon run must be sacrificed," wrote Interior Secretary Julius Krug in a 1947 memorandum that set the department's policy on the Columbia River. With that directive, the states and federal government built approximately 65 hatcheries to compensate for the colonies of dams built throughout the next 30 years. Wild salmon began a downward spiral from which they have yet to recover.

As the industrial machine rolled onward, hatchery critics maintained a quiet but steady hum. After two decades of reports that indicated hatcheries weren't making any difference in the number of returning fish, a team of experts recommended to Congress in 1950 that future hatchery construction be deferred until they determined if existing hatcheries were effective. As a result, hatchery managers began to clip salmon fins in order to track returns and rate of capture by fishermen.

They learned that the numbers of hatchery fish returning to their spawning grounds were small compared to the vast number of fish released, but that commercial and recreational fishermen were catching predominately hatchery fish. The findings did not spur the agencies to examine whether wild fish were declining or why hatchery fish were dying in such large numbers. Instead, an emboldened hatchery fan club of fishermen lobbied politicians to spend more money on more hatcheries.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, the Interior Department and state agencies built dozens of additional hatcheries. Under pressure to demonstrate that tax dollars were spent wisely, hatchery managers began to provide better disease protection and delayed release of the fish into the wild until the smolts were older. Both decisions increased the rate of returns and pleased critics and fishermen.

Still, evidence mounted that hatchery production was not keeping pace with disappearing habitat and diminishing wild runs. Between 1976 and 1977, hatchery runs of coastal coho salmon in Oregon dropped from 3.9 million to 1 million. Across the Northwest, hatchery and wild runs were failing. Something was not working. Yet due to the chronic lack of monitoring and evaluation that had plagued the hatchery program since the 1870s, managers didn't know what had caused the collapse, nor how to fix the problem.

No one in charge

It would have made sense for the hatchery reform movement to have kicked into high gear following the revelations of 1977. But once again, politics kept the hatchery love affair alive.

It would have made sense for the hatchery reform movement to have kicked into high gear following the revelations of 1977. But once again, politics kept the hatchery love affair alive.

Just a few years earlier, in 1974, Federal Judge George Boldt had ruled that Indians were entitled to 50 percent of all returning fish. Prior to the ruling, the non-Indian community had been harvesting 90 percent of the catch.

"It was so tense," recalls Peter Bergman, who was the chief of salmon programs for Washington state at the time. "There were shootings on Puget Sound."

Rather than endure a politically charged reduction in fishing, the Interior Department built the Makah and Nisqually Fish Hatcheries and gave Washington state $33 million to build 10 additional facilities. To soothe the furious and frightened non-Indian fishermen, the government aimed to produce its way out of scarcity.

Bergman blames the continued faith in hatcheries on a huge and complex bureaucracy that doesn't hold anyone accountable. The players include state hatcheries, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service hatcheries, tribal hatcheries, and hatcheries run by private sports-fishing groups. In some cases, such as Bonneville, the state owns the hatchery but contracts with the feds to manage the facility. There are approximately 200 hatcheries in the Northwest, but no central entity oversees them, keeps track of the amount of fish produced, or even how many facilities exist. Information is squirreled away in literally hundreds of places. Add the huge personnel turnover within the agencies, and the fact that once fish are released into the rivers they don't return for six years, and it's clear why hatcheries are "run in a mindless fashion," says Bergman.

As wild salmon numbers continued to decline throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, more studies were called for and occasionally, those studies recommended reforms. But without significant financial commitment from legislators, no real change occurred. Then in 1999, three events conspired to shake the steady course of hatchery management.

The first occurred on March 16 - remembered by many fish managers as "a dark, dark day" - when the National Marine Fisheries Service listed nine more salmon runs under the Endangered Species Act. The agency would list two additional runs of Northwest chinook six months later.

For the first time, people in urban areas like Seattle and Portland felt the power of the Endangered Species Act. Suddenly, there were calls for restricted water use and new building codes to protect riparian areas. An investigation by the Portland Oregonian revealed that the federal and state agencies were planning to spend nearly $1 billion on salmon recovery programs for 2000 - nearly equivalent to the amount spent on health care for the entire state. For rural towns struggling to rebound from diminished logging in the aftermath of the spotted owl listing, the news landed hard.

Ron Yechout, the manager of a bank in rural Oregon, decided to fight back. The autumn before, while elk hunting, he had stumbled upon employees at Oregon's Falls Creek Hatchery clubbing hundreds of surplus hatchery salmon with baseball bats. He captured the bloody scene on video. As public furor grew over the potential impacts of the listings, Yechout began to show his home-movie.

"This salmon thing is the biggest artificial shortage ever created," says Yechout, drinking thin diner coffee near his home in Philomath. "How can they say we have endangered fish and then they're slaughtering thousands of perfectly good ones. This is a big bunch of political bullshit."

The video made headlines across the nation. Angry citizens demanded to understand how their tax dollars were being spent, and sued the Fisheries Service, claiming that there is no difference between hatchery and wild salmon (HCN, 10/9/00: Killing salmon to save the species). In the midst of this, Lichatowich released Salmon Without Rivers - the third major event.

These two last ingredients had the kick of cayenne and for the first time in a century, the agencies responsible for hatcheries found themselves in a political stew.

Desperate pragmatists

Into this mess stepped a new set of reformers. They surfaced at a banal conference center in the wake of the listing decision. A committee of state and federal agency directors, spurred by then-Sen. Slade Gorton, R-Wash., to investigate a solution for the most recent salmon crisis, recommended that a panel of independent scientists conduct a comprehensive evaluation of hatcheries on a case-by-case basis.

Long Live the Kings director Barbara Cairns, listening to the presentation, found herself counting off the ways the project would fail: An independent science panel wouldn't have authority to make any real change because it wouldn't control the state agencies' budget; without buy-in from the state and tribal managers, any suggestions from the panel would fall on deaf ears.

Long Live the Kings director Barbara Cairns, listening to the presentation, found herself counting off the ways the project would fail: An independent science panel wouldn't have authority to make any real change because it wouldn't control the state agencies' budget; without buy-in from the state and tribal managers, any suggestions from the panel would fall on deaf ears.

"I went up to (the chair of the panel) and said, 'I want in on this.' "

The plucky Seattle-area native and former legislative assistant for the environment for Sen. Joe Lieberman, D-Conn., got what she wanted. The nonprofit Long Live the Kings seemed uniquely qualified to lead a multi-agency effort: The group manages three hatcheries and has spent over a decade researching how hatchery fish can help wild stocks recover.

Over the past two years, the group has provided the panel of nine independent scientists with information on the history and goal of each hatchery and the status of the stocks and habitat. The scientists evaluate the hatchery to determine if it meets its goals without hurting wild-salmon recovery efforts. Long Live the Kings then coordinates with the hatchery managers to discuss how to implement the scientists' suggestions.

"We let the scientists be scientists and the managers be managers," says Cairns. "We create crosswalks between the two."

So far, the team has tackled 46 of the nearly 100 hatcheries in the region. And its findings have not all been glowing - in one case it has recommended the state shut down the facility, which the state plans to do July 1. Other suggestions range from changing the time when the run is spawned, to stopping the production of salmon that aren't native to the region, to installing screens on the pipes that suck river water into the hatchery - currently many of those pipes inadvertently suck and kill wild and hatchery fish as they migrate from the river to the ocean.

The scientists and Long Live the Kings hope that through this effort they will help to lessen the impacts of hatchery fish on wild runs, while creating more efficient and cost-effective facilities. They also want to take hatchery fish to the next level, and make them as much like wild fish as possible. While scientists on the panel say they're still exploring how to redesign hatcheries for a conservation purpose, they believe that rather than looking at how many fish the facilities should produce for harvest in two years they should be looking at how many fish society will need in the long term.

The scientists and Long Live the Kings hope that through this effort they will help to lessen the impacts of hatchery fish on wild runs, while creating more efficient and cost-effective facilities. They also want to take hatchery fish to the next level, and make them as much like wild fish as possible. While scientists on the panel say they're still exploring how to redesign hatcheries for a conservation purpose, they believe that rather than looking at how many fish the facilities should produce for harvest in two years they should be looking at how many fish society will need in the long term.

"I think in 200 years, we won't need dams anymore to produce energy, we'll have some other technology. Hatcheries should be used to hang on to genetic resources until then," says Don Campton, one of two geneticists on the panel and the regional geneticist for the Fish and Wildlife Service. "I might be pipe-dreaming, but what other dream would somebody like to have?"

Managers seem enthusiastic about the calls for change. At a press conference last February, Jeffrey Koenings, director of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, announced, "I am committing my agency to implementation of this."

While this project is specific to the 100 hatcheries in the Puget Sound and in Coastal Washington, Cairns says that the scientific framework could be applied throughout California, Oregon and Idaho. Rowan Gould, the Portland-based deputy assistant director for fisheries of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, agrees:

"I think what they're doing is absolutely the right way to do business," he says.

Already, others are using the framework as a model. At the prompting of Congress, the Northwest Power Planning Council (a congressionally appointed committee funded by hydropower revenue that aims to mitigate for the effects of dams) is undergoing a review of how artificial production affects wild fish in the Columbia River Basin. Beginning in late June, a team of 10 scientists will begin to review the over 120 hatcheries in the basin, with the Power Planning Council acting as facilitator much like Long Live the Kings. The reform effort in Washington "has given us a lot of insights about how to conduct our review," says Bruce Suzumoto, a fisheries scientist for the council.

Already, others are using the framework as a model. At the prompting of Congress, the Northwest Power Planning Council (a congressionally appointed committee funded by hydropower revenue that aims to mitigate for the effects of dams) is undergoing a review of how artificial production affects wild fish in the Columbia River Basin. Beginning in late June, a team of 10 scientists will begin to review the over 120 hatcheries in the basin, with the Power Planning Council acting as facilitator much like Long Live the Kings. The reform effort in Washington "has given us a lot of insights about how to conduct our review," says Bruce Suzumoto, a fisheries scientist for the council.

The fishing community is watching both efforts with uncharacteristically united support.

Joel Kawahora, a former Boeing engineer who returned to commercial fishing several years ago because "he hated the people and missed the water," says fishermen need hatcheries because the habitat for wild fish has become so poor.

"Have you ever watched your mother die of cancer? That's what it's like watching the urbanization around here," says Kawahora glancing outside a coffee shop near the crowded Seattle pier where his boat is parked. "There isn't a stream in the Puget Sound that isn't messed up."

Many fishermen, he says, understand that hatcheries have been mismanaged, but until the dams are gone and there are more fish, he says, the fishing community will fight for hatcheries.

Smiley-face reform

Yet many fish biologists and conservationists believe these reforms are simply a way for state and federal agencies to continue to feed off the salmon cash cow and to perpetuate the myth that we can have healthy salmon populations without restricting the number of fish we harvest or restoring habitat.

Yet many fish biologists and conservationists believe these reforms are simply a way for state and federal agencies to continue to feed off the salmon cash cow and to perpetuate the myth that we can have healthy salmon populations without restricting the number of fish we harvest or restoring habitat.

"We're just putting a smiley face on what we want to do, (which is use hatcheries) the way we've always done it," says Joe Whitworth, executive director of Oregon Trout. "It will take years for the agencies and the fishing-dependent citizens to wean themselves from the hatchery narcotic."

Implementation will require money. Lots of it. While the majority of funding for hatchery reform has come from federal appropriations, money to implement change will come from the states and tribes, says Cairns. This spring, the Washington Legislature appropriated $1.25 million to begin implementing the scientists' recommendations, but that is a drop in the bucket. Cairns has no idea of the total cost but, she says, "when I throw a figure out there, people usually faint."

Beyond such difficulties lies the fundamental issue of whether reforming hatcheries will really do what it purports.

"Hatchery reform is like a chameleon. I think they're only changing the fabric; the structure is still the same," says Bill Bakke, director of the Native Fish Society. Bakke stands in the middle of Ten Mile Creek, a small wild stream near the Oregon Coast. The trees wear shawls of delicate moss and the salty air promises that this stream has only a few more miles to run before it reaches the ocean. Bakke sloshes forcefully across the river in tall khaki waders; with a silver cane, he points out salmon redds on the riverbottom.

"Hatchery reform is like a chameleon. I think they're only changing the fabric; the structure is still the same," says Bill Bakke, director of the Native Fish Society. Bakke stands in the middle of Ten Mile Creek, a small wild stream near the Oregon Coast. The trees wear shawls of delicate moss and the salty air promises that this stream has only a few more miles to run before it reaches the ocean. Bakke sloshes forcefully across the river in tall khaki waders; with a silver cane, he points out salmon redds on the riverbottom.

"I'm under orders to kill every hatchery fish I can find," he says chuckling. We round the corner, stumbling through ferns; a steelhead jumps from the depths of the stream, arches and dives back into the deep pool. In the middle of the river, atop a sand bar, lies a fallen tree the size of a Suburban.

"That's what we really need to recover wild fish," says Bakke pointing to the tree, bleached as bone. Two-hundred- to 400-year-old trees create spawning areas for steelhead and rearing grounds for young salmon smolts, says Bakke. And size matters: Smaller logs are easily swept away by the current; even large trees will eventually be carried out to sea.

"That was once a 600-year-old Sitka spruce," he says pointing at a small riffle in the water. "The power of water is amazing."

Throughout the region, over 50 percent of habitat that includes trees this size has been altered. Even when only 25 percent of an area is logged, its hydrology and species composition change dramatically. According to Bakke, we've created an ecological hole that we can't fix with engineering.

Throughout the region, over 50 percent of habitat that includes trees this size has been altered. Even when only 25 percent of an area is logged, its hydrology and species composition change dramatically. According to Bakke, we've created an ecological hole that we can't fix with engineering.

That's why many scientists agree that hatchery reform isn't even half the solution.

"I can't think of one steelhead population that we can fix by just adding more fish," says Mark Chilcote, a fisheries biologist for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. "Even if we could get hatchery fish exactly like wild fish, it wouldn't help these populations."

In a recent study in which he reviewed salmon data collected over 26 years from 12 Oregon rivers, Chilcote concludes that hatchery fish are bad breeders; in many cases they were one-eighth as effective as native fish. He says that adding more hatchery fish to wild populations leads to their demise because when hatchery populations breed with wild fish, as they inevitably do, they in effect deplete the stream of its most effective spawners.

If we really want to recover wild populations, says Chilcote, we need to create additional habitat.

Given society's current trajectory, that's not likely to happen. With an expected population of 85 million in the Northwest by the end of the century, many predict wild salmon are doomed.

Back in Seattle, Barbara Cairns looks out over the sea of tourists and business people, and remains adamant.

"So, it takes 150 years to grow 150-year-old trees. What do we do in the meantime? Play ping-pong and eat bon-bons? I'm not willing to lose hope," she says grinning stubbornly. "I believe if we are smart and use hatcheries in concert with habitat recovery, the fish will come back. Hatcheries will be our holding tanks until then."

It's a bet the Legislature is willing to make. And it's a stance that makes even critics like Salmon Without Rivers author Lichatowich think twice.

"This reform effort is different from anything I've ever seen before, so I'm optimistic," he says. "Still, based on the history and the entrenched bureaucracy of the state agencies, I have to say, I'll believe it when I see it.' "

Related Links:

Long Live the Kings, www.longlivethekings.org

Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, www.critfc.org

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum