the film

forum

library

tutorial

contact

|

|

Portland Harbor Cleanup Could Cost Billions,

Provide Little Health Benefit, Industry-sponsored Study Says

by Scott Learn

The Oregonian, February 8, 2012

|

A study paid for by three of Portland's biggest industries contends there could be high costs -- from $445 million to $2.2 billion -- and minimal health benefits from the Superfund cleanup of contaminated sediment in Portland Harbor.

A study paid for by three of Portland's biggest industries contends there could be high costs -- from $445 million to $2.2 billion -- and minimal health benefits from the Superfund cleanup of contaminated sediment in Portland Harbor.

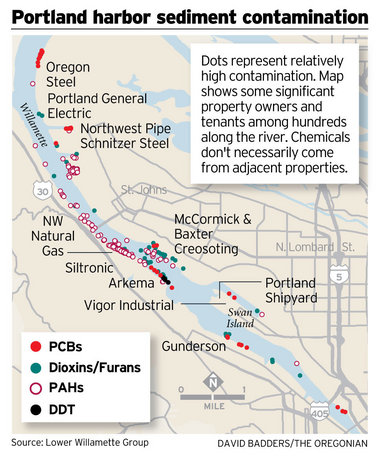

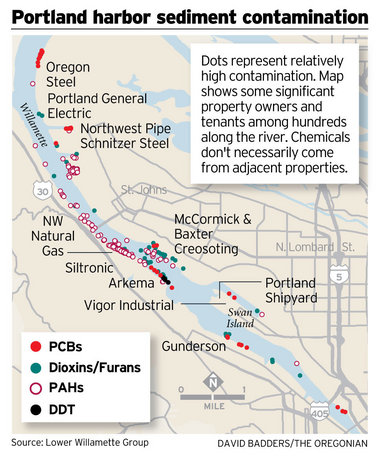

The study, commissioned by harbor businesses Schnitzer Steel, Gunderson and Vigor Industrial, is the first attempt to pin down costs and benefits of Oregon's largest cleanup, covering a heavily industrialized 10-mile stretch of the Willamette River. Costs will fall on industry, past and current property owners, the Port of Portland and city of Portland sewer ratepayers.

Eleven years after the federal Superfund designation, the study targets the Environmental Protection Agency, which will decide on cleanup details. As river advocates note, it was conducted for three of the companies on the hook for cleanup costs.

David Sunding, co-author of The Brattle Group study, said even unrealistically high assumptions about the number of people eating large amounts of contaminated fish from the harbor -- the main human health risk -- show little return in reduced cancer cases.

But that's not reflected in EPA's analysis to date, said Sunding, a resource economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

"I was really struck that the EPA would require a set of companies to spend potentially billions of dollars and not have any idea what that would accomplish," he said.

EPA officials said the study's conclusions are premature and incomplete. The agency is overseeing a detailed analysis of costs and risk reduction that's due by the end of March, part of the prelude to the cleanup.

River advocates and tribal officials say the companies want to minimize their liability, in some cases after decades of pollution. Since 2004, Oregon has recommended limiting consumption of resident harbor fish -- mainly carp, bass and catfish -- because they carry high levels of PCBs, a probable carcinogen largely banned in the 1970s.

The study "is very calculated and it's very transparent where they're trying to get," said Travis Williams, executive director of Willamette Riverkeeper.

The study "is very calculated and it's very transparent where they're trying to get," said Travis Williams, executive director of Willamette Riverkeeper.

Cleanup costs hinge largely on how much contaminated sediment will have to be dredged, instead of capped or left alone. Dredging removes the contamination for good, but it's more expensive.

The study's lowest cost -- $445 million -- assumes dredging about 3 percent of the harbor's roughly 2,200-acre riverbed. The highest cost -- $2.2 billion -- assumes dredging 16 percent.

That cost range isn't out of line with EPA's estimated costs for Superfund cleanup of the lower Duwamish River in Seattle. EPA estimates for that 5-mile-long project, half the length of Portland harbor, range from $230 million to $1.3 billion depending on the amount of cleanup.

Calculating the risks and benefits is trickier.

EPA wants to reduce cancer risk for people who regularly eat fish from the harbor for 30 to 70 years to 1 in a million, a common national yardstick. It's fish consumption estimates range up to 23 8-ounce meals a month in the case of tribal members.

The Brattle Group study takes the fish consumption numbers, which industrial groups contend are overblown and tribes say are low, then assumes cleanup will achieve EPA's cancer-risk benchmark -- it may not.

The study figures a "highly conservative" maximum of 73,000 people potentially eating fish only from the harbor. Then it plugs in the EPA's value for a life saved, starting at a high of roughly $8 million and diminishing at a 5 percent annual clip as the years pass -- a life saved today is worth more, in stark economic terms, than a life saved decades from now.

In the worst-case scenario -- people eating whole, uncooked fish, which have higher contaminant levels than cooked fillets -- lives saved would total 72 over 70 years, the study says, for a maximum benefit of about $112 million.

"Even making conservative assumptions, those benefits wouldn't justify a $2 billion cleanup effort," Sunding said.

Alan Sprott, a Vigor Industrial vice president, said he'd like a study of how many people eat fish from the harbor, given the jobs at risk if costs soar. The company, which owns a shipyard on Swan Island, knows some cleanup is necessary, he said, but it needs to be grounded in a realistic risk assessment.

The business concerns have caught the ear of of Oregon's politicians. In November, Oregon's two Democratic senators and two of its Democratic representatives -- Earl Blumenauer and Kurt Schrader -- asked EPA many of the same questions raised in the study.

EPA officials said the study doesn't include the damage done to riverbed organisms -- key to a healthy river. PCBs, the study's focus, are the main risk in the harbor, they note, but other pollutants play a role, too.

Subsistence fishing is popular among some ethnic groups, particularly low-income Asian and Slavic immigrants.

"People are scared to fish (in the harbor) now," said Oleg Kubrakov, a Slavic community leader who takes teenagers from his Portland-area church on fishing trips. "If there was an acceptable environment, I think a lot of people would."

The traditional lands of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde included the harbor. Eirik Thorsgard, the tribes' historic preservation officer, said the community needs to think long-term.

"I don't want to see anyone hurt," he said, "from exercising their right to take a fish out of the river."

Scott Learn

Portland Harbor Cleanup Could Cost Billions, Provide Little Health Benefit, Industry-sponsored Study Says

The Oregonian, February 8, 2012

See what you can learn

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum

A study paid for by three of Portland's biggest industries contends there could be high costs -- from $445 million to $2.2 billion -- and minimal health benefits from the Superfund cleanup of contaminated sediment in Portland Harbor.

A study paid for by three of Portland's biggest industries contends there could be high costs -- from $445 million to $2.2 billion -- and minimal health benefits from the Superfund cleanup of contaminated sediment in Portland Harbor.

The study "is very calculated and it's very transparent where they're trying to get," said Travis Williams, executive director of Willamette Riverkeeper.

The study "is very calculated and it's very transparent where they're trying to get," said Travis Williams, executive director of Willamette Riverkeeper.