forum

library

tutorial

contact

Agreement Expected Soon

on Idaho River Flows, Fish

by Rocky Barker

The Idaho Statesman, July 2, 2001

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Agreement Expected Soon

by Rocky Barker

|

Goal is to keep fish, electricity, irrigation going

Idaho Power Co. and federal officials

may announce a deal this week that

they hope will strike a balance

between using water to help

endangered salmon migrate and

using it to irrigate crops and to

produce electricity.

Idaho Power Co. and federal officials

may announce a deal this week that

they hope will strike a balance

between using water to help

endangered salmon migrate and

using it to irrigate crops and to

produce electricity.

For more than a decade, salmon advocates and federal officials have sought Idaho water to aid the struggling fish.

Farmers and Idaho Power Co. kept federal fisheries officials at bay by flushing excess water from Snake River reservoirs downriver at a price. In light of this year's drought and energy crisis, Idaho water managers have reduced the added flows for salmon to a trickle.

That has prompted salmon advocates and federal officials to step up their campaign to obtain water from the state by all means possible. These legal and bureaucratic efforts have added to the growing uncertainty over Idaho's $2.5 billion irrigated-agriculture economy and the electric rates for Idaho Power's 384,000 customers. Less water would dry up croplands and raise power rates.

There was water to lease -- 200,000 acre-feet of it by state estimates -- when the utility bought back power normally used to pump it onto crops. But the Bonneville Power Administration, which pays for salmon programs, and Idaho Power Co. couldn't strike a deal.

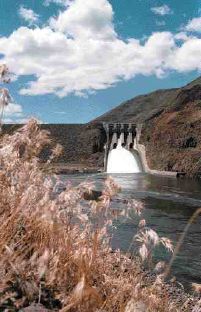

The National Marine Fisheries Service has been pushing Idaho Power to drain a third of Brownlee Reservoir by July 31 for free.

"Everybody knows fish need water, especially this year," said Nicole Cordan, Save Our Wild Salmon legal director. "We have been pushing very hard to for federal agencies to put in a call for Upper Snake Basin water, and we will continue to do that."

It comes in the wake of a federal decision in April to withhold water in the Klamath Basin in southern Oregon from irrigators under the auspices of the federal Endangered Species Act.

Under federal court order, the Bureau of Reclamation cut off water to 200,000 acres of farmland to protect endangered Lost River suckers, short-nosed suckers and coho salmon in the Klamath River. A similar cutoff of irrigation water in Idaho would idle more than a million acres.

"I cannot stress enough how important ... the consequences of the Klamath Basin decision are for Idaho agriculture," Rep. Mike Simpson, R-Idaho, said.

These new pressures are, in part, the result of the region's choice to keep four federal dams in Washington on the Snake River intact, at least for now. In December, federal officials chose a suite of actions to aid salmon -- including the use of Idaho water -- instead of breaching the four Army Corps of Engineers dams in Washington.

Twelve different salmon and steelhead stocks are endangered in the Columbia River Basin.

For Idaho Power and irrigators, the most problematic is the fall chinook.

Historically, these salmon emerged from their eggs in the main stem of the Snake and in the mouths of tributaries in the winter. Then they migrated to the ocean on the end of the runoff of the following year in late June and early July.

But now changes in river temperatures and other habitat alterations caused by upstream dams in Idaho have retarded the growth of the fall chinook. These changes have delayed their migration until later in the summer when flows are low and the water is hotter, said Dan Daley, a Bonneville Power Administration Fish and Wildlife planner.

That's why the National Marine Fisheries Service wants water from Idaho -- specifically from Idaho Power -- to offset the effects of the habitat changes on the fall chinook.

Idaho Power and state officials challenge the Fisheries Service's conclusion. They also dispute the idea that increasing river flows with Idaho water helps the fall chinook. Idaho Power also argues that the federal government really wants the water to offset the effects of its four dams on the lower Snake and other dam operations on the Columbia.

"Our studies shows there has not been a negative impact on fall chinook caused by any temperature changes attributed to the Hells Canyon Complex," said John Prescott, Idaho Power vice president for generation.

The increased demand for Idaho water created by the December dam decision was delayed until the completion of negotiations among the state of Idaho, irrigators and the Nez Perce Tribe over water rights.

Those secret talks have lumbered on without resolution. Neither side will comment.

But if those talks don't prompt federal legislation, the pressure for more Idaho water will continue.

Since the early 1990s, Idaho water users have sent 427,000 acre-feet of reservoir water from the Snake, Boise and Payette rivers downstream to aid salmon. That would be enough water to keep Niagara Falls flowing for two and a half days. This year, only about 38,000 acre-feet was released, because of the drought.

The Bureau of Reclamation -- the federal agency that controls Boise, Payette and Snake River reservoirs such as Arrowrock, American Falls and Cascade -- was given one-year approval for its operations. But it must show that the operations of its Idaho reservoirs don't jeopardize the survival of fall chinook.

Salmon advocates and the Nez Perce Tribe -- if its negotiations aren't fruitful -- could bring a lawsuit similar to the case made in the Klamath Basin.

Both the Fisheries Service and salmon advocates say the pressure to use Idaho water for salmon would drop significantly if Congress would breach the four lower Snake River dams.

"If there were major changes at another stage in the fish's life- cycle like some changes in the lower Snake migration corridor, it would make it easier for the fall chinook population to recover," said Brian Brown, assistant regional administrator for the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Norm Semanko, executive director of the Idaho Water Users Association, is highly skeptical. "I don't believe for a minute that taking those dams out will take away their demands on Idaho water," Semanko said.

He and others who control Idaho water are willing to allow leasing of water on a willing-seller, willing-buyer basis. In a drought year like this one, they don't want to have to give up the water that supports rural economies.

Idaho irrigators oppose any attempt to force them to give up water; they also oppose the withholding of federal reservoir water without compensation, as in the Klamath Basin. Idaho has depended on political muscle to prevent this approach. But even with a Republican in the White House, that power is limited.

Still, the all-Republican Idaho congressional delegation forced federal officials back to the table with Idaho Power.

The Fisheries Service and commission staff met with Idaho Power officials June 22 in an attempt to reach an agreement.

"From our point of view, the meeting was very productive and beneficial," Russ Jones, an Idaho Power spokesman, said last week.

Jones said an agreement may be announced this week.

Even if a deal would resolve the immediate threat to the company's water and electric generation, the uncertainty remains: The license for its Hells Canyon Complex of dams, which includes Brownlee Reservoir, will expire in 2005.

The endangered fall chinook are expected to be the toughest issue for the company to resolve in its effort to get a new license.

Under federal law, the Fisheries Service has the right to require the company to reopen passage for the salmon to the hundreds of miles of spawning habitat the dams shut off in the 1950s.

That's why the utility is urging Idaho officials to take a new look at the state's position on the four lower Snake dams.

Idaho Power isn't calling for breaching, said Greg Panter, the company's vice president for political affairs. But it realizes that as long as the four Washington dams cause migration problems for salmon, the salmon's fate and the fate of the Hells Canyon dams will be intertwined.

"Congress can resolve the Lower Snake dam issue; it can't get us a new license," Panter said.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum