forum

library

tutorial

contact

Nature Again Turns Against Returning Fish

that Already Face Long Odds

by Rocky Barker

Idaho Statesman, May 20, 2017

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Nature Again Turns Against Returning Fish

by Rocky Barker

|

Idaho's salmon run this year is beginning to look bleak.

Idaho's salmon run this year is beginning to look bleak.

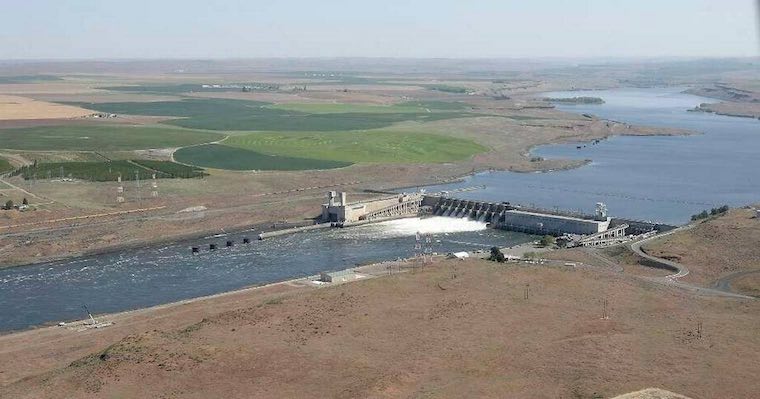

Oregon and Washington officials shut down fishing season on the lower Columbia River earlier this month because so few spring chinook heading for spawning grounds in Idaho and other Snake River tributaries had shown up at the Bonneville Dam near Portland. Idaho's Fish and Game Commission took a wait-and-see stand Wednesday on whether to close fishing season, because fewer than 400 salmon had made it to Lower Granite Dam on the Snake River in Washington, the last of the eight dams between the Pacific Ocean and Idaho.

For the past decade, nearly 30,000 spring chinook had returned on average by now. Idaho Fish and Game biologists worry they won't have enough salmon returning to supply brood stock for the fish hatcheries that account for 80 percent of the run -- and might mean no fishing at all for spring and summer chinook, which are the salmon most Idahoans catch. The chinook that are born wild and not in hatcheries make up 20 percent of the run, and they aren't much better off.

Salmon are born in tributaries like the Salmon and the Clearwater rivers, and are swept by rushing spring flows to the Snake, the Columbia and the ocean as year-old smolts. They spend two, three or four years in the ocean before starting their journeys home to spawn, and die, in the rivers where they were born.

Watching the number of returning spring chinook run is important because the early return is a harbinger for what's ahead and for Idaho's other three species of salmonids that are listed as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

For more than a decade, the Columbia River and its tributaries have seen relative abundance, with favorable ocean conditions contributing to good runs of salmon and steelhead, which bring joy to anglers and spiritual sustenance to the region's Indian tribes. It's also eased the pressure on the region's dam managers to take drastic action -- such as removing dams.

The Bonneville Power Administration is the regional agency that sells the hydropower produced at the federal dams on the Columbia and Snake rivers. It has spent $15 billion over the past 25 years on modifying dams, restoring habitat, expanding and operating hatcheries, and conducting research and predator-control programs to improve the lot of salmon and steelhead.

Since 2000, mostly ideal ocean conditions boosted the salmon's food sources and limited their predators. That's critical to healthy populations because the ocean is where salmon spend two-thirds of their lives, feeding, growing and gaining strength for their arduous return trip upstream. Salmon, especially those raised in hatcheries, have been returning to Oregon and Washington at rates not seen since the last of the dams were built in the 1970s.

But abundant ocean conditions no longer favor salmon and no longer mask the unfavorable conditions in the Northwest rivers. A so-called "blob" of warm water in the Pacific Ocean has reduced salmon productivity by as much as a factor of 10. Add to that the regular ocean cycles and the warmer river temperatures, increasing numbers of predators and low river flows of recent years, and biologists worry today about the returns not just of the endangered wild fish, but also of the much greater number of hatchery fish.

We're beginning a five-month project, in conjunction with our McClatchy colleagues, to examine the challenges that face our salmon, our economy and our culture. We want to answer the question: Can the salmon be saved?

ECHOES OF THE 1990S?

This spring's run looks disturbingly like the 1990s, when salmon numbers crashed, especially for those Idaho fish that must survive all eight dams on both legs of their migration.

Wild stocks dropped so low that, beginning with the Snake River sockeye salmon in 1991, 13 species of Columbia River Basin salmon species were listed as threatened or endangered. Idaho's Snake River sockeye were listed as endangered. The Snake River spring-summer chinook, fall chinook and steelhead were listed as threatened, a slightly less-dire and less-restrictive category.

That was a turning point. Once the fish were listed, the act forced federal dam, water and land officials to ensure that the actions they take don't further endanger the survival of the fish. That sounds simple, but it's a complex, bureaucratic and restrictive process. And it gives sportsmen, environmentalists and Indian tribes more openings to scrutinize the government's plans and efforts -- and take them to federal court.

It was in the 1990s that biologists and notably the Idaho Statesman editorial board began to talk seriously about breaching the four lower Snake Dams in Washington to maintain the fish that spawn in central Idaho, the wildest, most pristine habitat left in the lower 48 states.

The dams have turned the river into a series of reservoirs that slows migrating the salmon as they go from freshwater to saltwater fish. Some fish die in the hydroelectric turbines, despite bypass systems that divert them into barges that carry them through the dams. Most smolts are "spilled" over the dams, now aided by fish "slides" that increase survival but result in what scientists say is "delayed mortality" after the salmon reach the Columbia estuary below Bonneville Dam near Portland.

NOAA scientists say that even with the improvements at the dams made since 2000, more needs to be done to improve migration of the wild Snake River salmon if they are to be self-sustaining. Breaching the dams to return the river to a more natural state is considered the best, but perhaps not the only, way to do that.

Talk of breaching or removing the dams created a powerful backlash. Many Northwesterners take pride in the colossal accomplishment of harnessing the river for cheap, reliable, abundant electricity, an effort born in the depths of the Depression. Those Northwest dams brought power, jobs and prosperity to rural communities. That electricity produced the aluminum that went into the bombers and powered the reactors that made the nuclear cores for bombs dropped on Japan to end World War II.

The four dams also created opportunities more than 500 miles inland at ports in Clarkston, Wash., and Lewiston. For decades paper, lumber and other products were shipped to market down the Columbia, and wheat is still barged downstream. A small group of farmers pump water from the pool behind one dam to irrigate their crops.

JUDGES STEP IN

The Columbia River system once sustained 8 million to 16 million salmon returning annually. But 150 years of overfishing, habitat destruction, dam building and water pollution took its toll. By 1995, less than 700,000 returned.

Once the fish were listed under the Endangered Species Act, the onus was on the federal government to show its actions were helping, not harming, the fish. Three federal judges since 1994 ordered the BPA, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation to take increasingly stronger steps to reduce or offset the effects of the dams on salmon.

The latest was U.S. District Judge Michael Simon in 2014, who ordered the agencies to conduct a new environmental review and write a new biological opinion on the effects of the dams. He expressed frustration that since Idaho's lawsuit against the dam plans in 1993, the agencies had four times "ignored the admonishments of Judge (Malcolm) Marsh and Judge (James) Redden to consider more aggressive changes ... to save the imperiled listed species."

In 2014, 3.5 million fish, mostly hatchery salmon, returned to the Columbia River and its tributaries.

The federal agencies began their latest review in 2016 with a series of meetings, including one in Boise, that generated more than 250,000 comments nationwide. The agencies must come back in 2018 with an immediate plan for operating the dams and in 2021 with a final decision on a long-term plan. Simon said that plan must include a review of breaching the four Snake dams.

WHAT'S TO COME?

This is a story I have covered since 1990, having been up and down the Columbia and Snake rivers and to the headwaters of the Salmon River near Stanley, 870 river miles from the Pacific.

It took me across the country in 1999, when I stood with utility CEOs, anglers, environmentalists, and Republican and Democratic state officials on the banks of the Kennebec River in Augusta, Maine, as the Edwards Dam was removed.

In 2011, I watched federal officials (with the help of Jerry Dilley of Superior Blasting of Nampa) remove two dams on the Elwha River in Washington's Olympic National Park. I returned to the Kennebec in 2005 and the Elwha in 2016 to find them transformed into rich ecosystems, where everything from bottom-feeding bacteria to aquatic insects to salmon have returned in abundance.

I remain chastened by the faces of the working-class men and women in Maine who watched the Edwards Dam come down. They had grown up working at the textile mill the dam had once powered. They weren't celebrating. They were crying as the river washed away the last vestiges of the way of life they'd thought would last forever.

Despite the endless court cases and the billions spent on dams, the future of Idaho's salmon remains as uncertain today as in the 1990s when they were protected by the nation's most powerful environmental law. So the Statesman is sending me to follow the salmon home to Idaho again.

I'm joined by videographer Ali Rizvi, who was part of the McClatchy team that won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting for its work on the Panama Papers story, revealing the shadowy world of offshore banks and corporations. Follow us on our trip beginning in Astoria, Ore., this week on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.

This is the first of several trips we hope will illuminate what humans can do to best help the fish that swim through all our lives in a time of economic transition and rapid climate change.

Related Pages:

Lower Snake River Farmers Seek Federal Ruling to Allow Idaho Salmon to Go Extinct by Rocky Barker, Idaho Statesman, 12/7/16

Video Link:

Opinions Gathered at Boise Meeting on Dam Salmon Issues, by Staff at the Idaho Statemsan.

A Boise steelhead angler's view on dams, by Staff at the Idaho Statemsan.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum