forum

library

tutorial

contact

Analysis: Chasing

Demons in the Ocean

by Bill Rudolph

NW Fishletter, May 14, 2015

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Analysis: Chasing

by Bill Rudolph

|

I will be retiring next week, and decided to use this space to look back on the last 334 issues of NW Fishletter, to get a notion of what the region has learned about getting fish past dams since I took over as editor in 1996.

Those were weird times. Scrolling back down memory lane through the Fishletter archives, I found an old story in NW Fishletter #9 that reported Oregon senator Mark Hatfield called regional NMFS administrator Will Stelle on the carpet for not putting more fish in barges, to escape lethal dissolved gas levels in the Snake and Columbia rivers from high spill at the dams. Modifications to spillways later reduced those lethal gas levels, but the state has been on a crusade for raising them ever since, no matter how much tougher it makes the return passage on adult fish.

In the issue prior to that, the new kids on the block, the Independent Scientific Review Group, "warned the Northwest Power Planning Council that without dramatic changes in Columbia River operations, salmon will be extinct by the next century. The group's 'new vision' of the Columbia system includes such potentially controversial recommendations as drawdowns and new flow regimes, all to restore and enhance habitat and promote genetic diversity. The key to saving salmon, said the report, lies in habitat restoration, a strategy that demands returning the river to a more normative state."

I took over the reins as fish reporter shortly thereafter, when schools of marauding mackerel were off the coast, preying on every smolt in sight. The mackerel were even cruising into streams on the west coast of Vancouver Island, wiping out the wild coho smolts.

We started covering the issue, after a devastating El Nino took hold in 1997, followed by another one a couple of years later. The Snake River salmon and steelhead runs were in extremely poor shape, but so was just about every other salmonid stock in the Northwest.

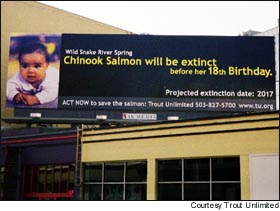

The dismal returns led to some far out studies, a lot of hand wringing and more talk about reservoir drawdowns to speed fish downstream and dam breaching on the lower Snake. According to one 1999 study by dam busters, the Snake spring Chinook were going to be functionally extinct by 2017 unless drastic measures were taken to improve passage conditions.

Oops. Contrary to the predictions from that analysis, the salmon runs turned around all by themselves.

That analysis was called the Doomsday Clock, and has since been scrubbed from fish advocates' websites. But, the other day, I found it lurking in the digital dustbin of history on a StreamNet server. The hoopla generated over that analysis even included its own billboard in downtown Portland.

In those days, a few farsighted scientists on both sides of the border had begun to realize that the ocean played a huge role in this survival story. It just so happened the flip side of that late-90's El Nino produced a powerful La Nina and such productive conditions for juvenile salmon in the nearby Pacific Ocean that smolt-to-adult return rates in the Columbia Basin skyrocketed from one-quarter percent to ten times that, and even more, in some cases.

In those days, a few farsighted scientists on both sides of the border had begun to realize that the ocean played a huge role in this survival story. It just so happened the flip side of that late-90's El Nino produced a powerful La Nina and such productive conditions for juvenile salmon in the nearby Pacific Ocean that smolt-to-adult return rates in the Columbia Basin skyrocketed from one-quarter percent to ten times that, and even more, in some cases.

Unfortunately, the Doomsday Clock study was not buried deep enough. It was disinterred a few years ago in an article in High Country News, and its results were taken to heart by the federal judge who was overseeing the complicated federal plans to keep dams operating and fish runs from winking out.

But it's not the salmon plans that have turned the runs around, or the judge's tinkering with them. The ocean turned them around before the plans got off the ground. And since the turn of the last century, the near ocean has become a much more productive pasture for young fish on their way north.

It is a story NW Fishletter has been covering for nearly 20 years. See here, and here, for bookends of that coverage.

And despite the billions of dollars spent on improving habitat, hatcheries, hydro passage and harvest strategies, the ocean alone can create conditions that are able to boost SARs by an order of magnitude in the space of a couple of years. All that effort at habitat restoration will be lucky to boost some of these runs by 20 percent.

We would never have learned much about this if all those salmon runs hadn't been listed for protection under the ESA. The listings gave NMFS a chance to develop PIT tag survival studies that revolutionized our understanding of fish survival, new research that some fish agencies like Oregon's fought all the way. As more detection sites were added to downstream dams, there was no evidence of huge mortalities in the hydro system as predicted by states and tribes. They still cling to that story, and hypothesize that the big latent mortality bugaboo still exists in a fogbank of assumptions somewhere north of the tip of Vancouver Island.

Before the PIT tag studies came along, state and tribal fish biologists estimated that juvenile survival through the hydro system was on the order of 10 percent. But the early PIT tag results found that it was more like 50 percent, even before the water slides and other improvements were added in recent years. The CRiSP survival model (based on that growing PIT tag database) trounced the states' and tribes' FLUSH model as a more realistic picture of the juvenile migration.

In fact, those studies found that the survival of juvenile salmonids through the hydro system is probably about the same or even better than other major undammed river systems, like the Fraser or Sacramento systems, and more recent studies are showing that PIT tag survival results likely underestimate SARs by 25 percent or more. Improvements at the dams have led to survivals through the lower Snake to the estuary that compare or beat survivals when only the four mainstem Columbia dams were in place.

The value of barging fish downstream is still debated, even though years of survival studies have shown that steelhead gain a clear benefit. But that didn't stop a federal judge from boosting spill levels, and cutting the number of steelhead routed to barges, likely reducing the return of ESA-listed Idaho wild steelhead by tens of thousands of fish.

BiOp Judge James Redden and his science advisor were misled by spill advocates' claims of rosy returns. Nobody is debating whether juvenile survival has improved for inriver migrants, it has to some degree. But there is no proof that it's had beans to do with increasing adult returns. In one NMFS study we reported on in 2013, adult returns correlated better with about two dozen different factors before any freshwater components like river flow came into the picture.

But it has taken more than a decade to sort some of these things out. However, flawed results from earlier attempts at developing fish recovery strategies that wrestled with many uncertainties, like the PATH process, are still being cited by some stakeholders as reason enough to take out lower Snake dams.

The Plan for Analyzing and Testing Hypotheses sounded great in theory, but it used reconstituted spawner-recruit data, very early PIT tag data, and some assumptions that were very flawed. When the results were reviewed by several independent scientists, called a "weight-of-evidence" panel, they concluded there was no evidence for a "demon in the ocean" that affected fish survival, and gave more support to the FLUSH passage model that turned out to be dead wrong.

A minority of scientists involved in PATH turned out to be correct after they complained the reviewers were [www.newsdata.com/enernet/fishletter/fishltr68.html] ignoring the latest research. The BPA-funded CRiSP model was eventually vindicated. NMFS still uses a souped-up variant of that early model in its fish survival analyses.

By 2001, it was pretty evident that the ocean was playing a big part in the salmon survival equation, as noted in my first column, celebrating issue #100. It was called simply, "It's the ocean, stupid."

Fish returns that followed the ocean regime shift, now known as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, were nothing short of stunning. The 1999 Snake River spring Chinook count at Lower Granite dam added up to about 3,300 fish. It had been even worse in 1994, when only 1,100 showed up, thanks to an even earlier El Nino.

Then, in 2001, more than 172,000 springers showed up in the Snake River. At that point, the ink was hardly dry on the government's salmon plan.

So what have we learned since then?

I solicited help with this exercise from some of my well-worn sources, my very own weight-of-evidence panel. Not surprisingly, they all pointed to the ocean as the big kahuna. One of my most trusted sources, who had survived the struggles of the PATH process, was kind enough to send me this list of some of the things he felt the region has learned since those dark ages of the late 1990s.

That change could start this year or 10 years from now, nobody knows. But the billions spent fixing our wonderful basin, spilling a little more water, shooting a few thousand birds, or harassing a few hundred sea lions won't do much to make up for an ocean which, in the best of times, allows two or three juvenile fish out of every hundred to make it home. When it gets bad, only two or three in a thousand will get back.

Over the years, I have simply tried to follow the example of my old mentor and friend, the late Don Bevan, who stressed the importance of data and evidence. He was an illustrious emeritus fisheries professor at the University of Washington by the time our paths crossed, and he counseled me to take this job. Bevan led the first salmon recovery team that NMFS put together and was brave enough to counter the reservoir drawdown rhetoric that permeated the region in those days.

The next time fish runs crash, we can only hope that our response will be more realistic, and our expectations more humble. I think Don would agree.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum