forum

library

tutorial

contact

With Salmon Numbers Plummeting, Solution

Begins with Dialogue -- Even at the Coffee Table

by Rocky Barker

Idaho Statesman, December 26, 2019

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

With Salmon Numbers Plummeting, Solution

by Rocky Barker

|

"We could learn about each other, our challenges and our hope for a better future for kids and grandkids,"

-- Retired outfitter Jerry Myers

LEWISTON -- Retired outfitter Jerry Myers invited farmers who depend on the Snake River to get their wheat to market to come to his home in Salmon to see how the loss of steelhead blocked by the river's dams is hurting his community.

LEWISTON -- Retired outfitter Jerry Myers invited farmers who depend on the Snake River to get their wheat to market to come to his home in Salmon to see how the loss of steelhead blocked by the river's dams is hurting his community.

"We could learn about each other, our challenges and our hope for a better future for kids and grandkids," said Myers, who grew up on a ranch in the Palouse wheat country north of Lewiston.

Jeff Sayre, in the grain business from Lewiston, was sitting in the front row of the Idaho Outfitters and Guides Association symposium on salmon on Dec. 3 when Myers spoke. When the panel was over, Sayre, part of Snake River Multi-use Advocates, met with Myers and accepted the invitation.

"He said we could stay at his house," Sayre said. "We can do like our grandparents did, have a pot of coffee on and sit around the coffee table. I think we'll find out we have a lot of common ground."

The kind of dialogue that Myers and Sayre are starting is not isolated. Across the Northwest in 2019, the debate over salmon and dams shifted from the courtroom to state-sponsored forums, living rooms, city halls and riverbanks.

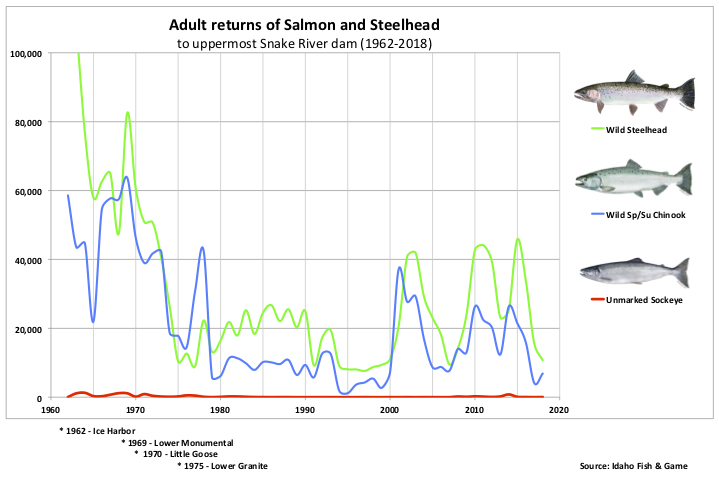

One of the reasons is that the number of wild salmon and steelhead has plummeted, especially in the Snake River and its tributaries. Only 17 endangered sockeye salmon made the trip home to Idaho's Sawtooth Valley this year, according to Idaho Fish and Game.

SALMON NUMBERS DISMAL

The return of wild steelhead remains extremely low after a preliminary estimate shows that only 7,500 spawned in Idaho in 2019, compared to a 10-year average of 28,388. The same is true of spring-summer chinook, with a still-not-final count of 5,162 compared with a 10-year average of 15,000. In 2001, 37,000 wild spring-summer chinook returned to Idaho, when Pacific Ocean conditions were ideal.

Once 8 million to 16 million salmon returned annually to the Columbia Basin, but 150 years of overfishing, dam building, habitat destruction and dewatering has sharply reduced the return.

The North Pacific is again experiencing a mass of warm surface water that increases the number of predators and reduces the quality of the tiny sea animals the young salmon eat. A similar phenomenon that oceanographers called the "blob," from 2014 through 2017, has contributed to the reduced returns over the past two years.

And now the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says another blob, which began earlier this year, is expected to continue at least into the summer. Some scientists warn that the Snake River salmon, which must go through eight dams on their migration between the Pacific and Idaho, could go extinct in the next 20 years if more isn't done.

Federal authorities have spent $17 billion on the fish, an icon of the Pacific Northwest. They are rewriting their plan for operating the region's hydroelectric dam system and will release preliminary results from their environmental review in February.

Five previous plans have been struck down as inadequate to protect 13 stocks of salmon and steelhead listed as threatened and endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act in the early 1990s.

SCIENTIFIC COMPROMISE

The new dialogue began late in 2018, when a long-standing scientific debate was put on hold by an agreement between the state of Oregon, the Nez Perce tribe and federal agencies that control the dams. They accepted a path to increase the amount of water that will spill over the eight dams away from the hydroelectric turbines.

And it allowed the Bonneville Power Administration, the agency that markets the electricity produced at the dams, to run more water through the turbines at the times of day when it is most valuable. The flex-spill agreement, which runs through 2021, got Oregon, the Nez Perce, and environmental and fisheries groups to commit to stay out of court for now.

"I sincerely believe there is a growing desire among people across the region to bring greater clarity, alignment and certainty to the challenging issues at play on the Columbia River," said Elliott Mainzer, BPA administrator. "During our work with the tribes and states through the Flexible Spill Agreement, we saw a deepening of trust, mutual understanding, and a willingness to work side by side on a more creative and solutions-oriented approach to meeting the goals of salmon recovery, reliable and affordable clean electricity, and economic vitality for the many communities that depend on the Columbia River system for their livelihoods."

SNAKE DAM DEBATE

What the spill agreement could not do, of course, is resolve the polarizing debate about removing the four federal dams on the lower Snake River that most fisheries scientists say would provide a four-fold increase in Snake River salmon survival. It remains a touchy issue politcally because it would mean dismantling a barge transportation system that wheat farmers in Idaho and eastern Washington say is critical to keeping them competitive.

Removing the dams also would require Bonneville to find alternatives for providing instant backup for the region's growing renewable energy sources. Just talking about alternatives angered farm and energy groups. That came to a head in April, when Mike Simpson gave a bold speech to the Andrus Center for Public Policy's salmon, energy and agriculture conference.

The Republican U.S. congressman from Idaho stopped short of calling for the removal of the dams, but he asked all interested parties to consider "what if" those dams come down? He urged the crowd to discuss what would be necessary to keep all of the groups across the Northwest whole if a solution were found for salmon and energy.

"The spill agreement opened a door and Mike Simpson went through the door and related the salmon issue to Bonneville's own financial issues," said John Freemuth, the Cecil Andrus professor of public policy at Boise State University.

Idaho Gov. Brad Little announced his own salmon working group, which has held meetings throughout Idaho on salmon policy. It has members of the agriculture, business, energy, salmon fishing and environmental groups, along with the Nez Perce and the Shoshone-Bannock tribes.

Little initially told the panel not to talk about dam removal, but members did when it became clear that the subject couldn't be avoided. Washington Gov. Jay Inslee's Orca Task Force recommended a study of dam removal, which was funded by the Washington Legislature and released Friday.

Inslee will begin a series of meetings throughout Washington to discuss the report and its findings, which largely lay out the arguments of dam supporters and opponents. The first is scheduled in Clarkston on Jan. 7 and will attract a lot of Idahoans from adjacent Lewiston.

A SOLUTIONS TABLE?

Even before the spill agreement, NOAA was holding a series of quarterly meetings with all sides of the salmon debate called the Columbia Basin Partnership Task Force. It has found common ground on long-term goals for restoring abundance of salmon throughout the region, even stocks that are not endangered, said Michael Tehan, NOAA Fisheries West Coast assistant regional administrator.

The federal dam agencies will release a court-ordered environmental impact statement in February, which will include their preferred alternative for operating the Columbia hydroelectric system so they move salmon to a path for recovery. Because of a directive from the Trump administration, they have to have a final decision by September.

Bonneville's Mainzer said his agency is "committed to maintaining this open and collaborative dialogue" through the review "and to do our part in helping bring the region together around long-term solutions."

Simpson and others have said that will take an act of Congress. To get there, Tehan said, a larger forum than his will have to be convened with everyone at the table.

Whether the sides spend 2020 preparing to go back to court or laying the groundwork for a deal likely will depend on what the agencies say in their review, even though no one thinks it alone can lead to a solution.

Perhaps it will begin around the coffee table in Salmon. Sayre said he doesn't mind that dam removal will be a part of any talks as long as it isn't the sole focus. "The issue has been sitting in the background for a long time," he said.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum