forum

library

tutorial

contact

Celilo Salmon Feast is More

Vibrant than Ever, Despite Flood

by Carol Craig

Indian Country Today, June 13, 2012

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Celilo Salmon Feast is More

by Carol Craig

|

An 18-minute black-and-white film, "The Last Salmon Feast of the Celilo Indians," was produced by the Oregon Historical Society in the late 1950s to document the final fish ceremony conducted before the opening of a new dam flooded the ancient fishing grounds known as Celilo Falls. However, the strength and perseverance of the tribal leaders did not stop after that day's ceremony and the annual Celilo Salmon Feast is still being held. The falls were silenced, but the tradition and culture of the river people remains vibrant. This year, the three-day feast attracted more than 500 tribal and nontribal people.

An 18-minute black-and-white film, "The Last Salmon Feast of the Celilo Indians," was produced by the Oregon Historical Society in the late 1950s to document the final fish ceremony conducted before the opening of a new dam flooded the ancient fishing grounds known as Celilo Falls. However, the strength and perseverance of the tribal leaders did not stop after that day's ceremony and the annual Celilo Salmon Feast is still being held. The falls were silenced, but the tradition and culture of the river people remains vibrant. This year, the three-day feast attracted more than 500 tribal and nontribal people.

In mid-April, as people approached the huge A-shaped longhouse next to the Columbia River at Celilo Village, thunderous drums were distant echoes of the pounding waters of Celilo Falls, considered a place designed especially for tribal people by the Creator. Inside, seven sacred songs were being sung seven times by seven drummers in line at the front of the longhouse. A brass bell rang out to count off each song as tribal people sang and danced in place. Women in traditional regalia stood shoulder-to-shoulder on the south side of the longhouse while men stood on the north side, moving their right hands in a gentle swing motion in unison with the drums.

This is the ritual known as the First Foods Ceremony, conducted to thank the Creator for bringing the resources back to the tribal people. As the foods reappear in the New Year the salmon returns first, then the roots spring up through the ground; in the summer, the huckleberry ripens as hunting and fishing continues. And then it is time to begin preparing the foods for winter use. "Elders teach the younger people that the salmon, deer and elk are our brothers and the roots and berries are our sisters and we should treat them as such -- with respect and caring for them," explained Priscilla Blackwolf, Yakama, who had her three-year old grandson in tow (wearing a traditional ribbon shirt).

The young women and girls in traditional wing dresses, moccasins and braided hair under colorful scarves were bustling in the kitchen preparing the traditional meal, while tribal and nontribal people milled outside. A small fire was surrounded by fresh-caught spring Chinook salmon on upright dogwood skewers. A huge square barbecue rack held more sides of salmon while another smoldering fire was being used to cook the deer and elk meat. Yakama brothers James and Ralph Kiona grabbed thick oven mitts, then flipped a huge rack filled with grilling salmon.

While the songs continued, young girls began placing long tule mats that would serve as plates today on the longhouse floor. Each plate would have a small piece of salmon, deer, roots, potato and berries. Young tribal men carrying large buckets scooped water into the cups beside the tule mats as the songs ended, and the people outside were told the meal was ready. Tribal elders were seated first, before other tribal people entered the longhouse. Nontribal guests were then invited in. Everyone was reminded throughout the ceremony that no recording devices or photography were allowed.

After everyone was seated on the floor they were instructed to take a sip of the chu'ush. Celilo Chief Olsen Meanus said, "We first thank the Creator for the water because without water nothing would be able to exist on Earth." Everyone was then invited to take the small piece of salmon, then deer and lastly the bitterroot and wapato (small potato). (The overflow crowd was served dinner outside, buffet style.)

Speakers from the Warm Springs, Umatilla and Yakama tribes talked during dinner, explaining the tradition. Ernie Selam stood. "We as adults are trying to set a good example for the children," he said. "We have to be the reverent example." He also told the Coyote story that had been passed down to him as a child -- he said generations ago the salmon were blocked from going upriver and tribal people were going hungry. Eventually, the salmon were freed by Coyote, and those who had blocked the fish were turned into swallows. "So every year when we see the swallows we know they are letting us know the salmon are coming."

The crowd was reminded of the silenced falls by Yakama drummer Davis Washines. "It was 55 years ago our world was turned upside down and we weren't allowed to do our scared ceremonies. We still have these memories; these songs come from the Creator," he said. "They speak of this discipline that we are talking about today."

At the end of the dinner, serving bowls brimming with preserved huckleberries floating in dark juice were passed around. Chief Meanus then asked everyone to take another sip of water, and with that dinner was over. The men filed out first, with the women following. Everyone walked all the way around the longhouse, then gathered to listen to Chief Meanus, who said, "Our new year has started. It's time for people to take care of all the resources that take care of our bodies that depend on these foods, and I am grateful to see all of you here."

With the ceremony completed, many tribal people gathered in the dancing arena next to the longhouse to dance, sing and socialize.

Echo of the Falling Water

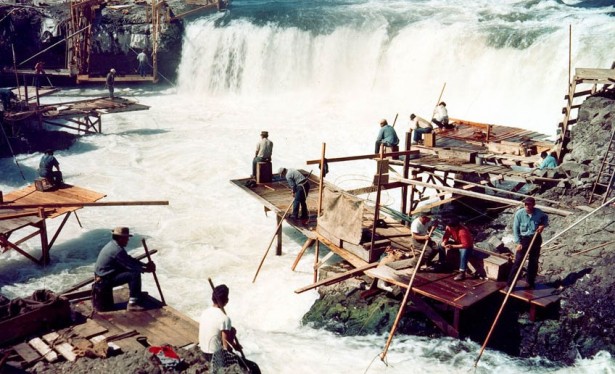

Since the beginning of time tribal people have fished along the Columbia River where the horseshoe-shaped Celilo Falls, a continuous, thunderous entity always provided one of the new year's first foods -- salmon -- for the tribal people.

For generations the falls was a gathering place for tribes from as far away as the Great Lakes, the Great Basin and the Great Plains. They brought food and other goods not available in that area for trading. "It was once the Wall Street of the river," says Ed Edmo, Shoshone-Bannock poet and storyteller who was raised at Celilo.

Fishing was done from April through October as the various salmon runs returned. Then, in the early 1930s, the federal government decided it was time to "tame" the Columbia, to make it produce electricity. Plans were made for the construction of The Dalles Dam, against the wishes of tribal leaders. They knew the dam would forever silence Celilo Falls.

Tribal leaders fought the plan but finally saw that they would have to acquiesce to the request from the Army Corps of Engineers to relocate Celilo Village. Edmo recalls the nontribal owner of the gas station/store who held out for more money, refusing to sell his businesses to the Corps. His property and store were condemned and torn down. "He stood there crying into his red hanky and watching the demolition," said Edmo.

On March 10, 1957, the floodgates at the dam closed, and six hours later the falls were buried in water. Some of the Yakama people, dressed in their regalia, stood on the hill beside the river to witness this execution. They pounded their drums; they sang to mourn the loss of the falls.

The Bonneville Dam was completed in 1937, then came the Dalles Dam, the first of the 31 federal dams on the Columbia and its tributaries that were built for power, irrigation and to prevent flooding. The federal government thought the tribal people would just lay down their fishing equipment and walk away, not understanding that their treaty right allowed them to fish in perpetuity. Instead, the people continued to fish there, even though some were arrested for not having a license. Lawsuits were filed, and after years in court, judges began to agree with the tribes that their fishing rights were the supreme law of the land.

The Creator's unwritten laws were being followed by those who continued living by the river instead of moving to reservations. And still today people who live here understand those instructions to care for salmon resources. "If we move from the river then we are no longer caretakers of the resources and worse, we are not Indian," said Margaret Saluskin, Yakama.

Salmon Populations Plummet

Most of the federal dams on the Columbia River and the Snake River were not fish-friendly. Fish populations dwindled. After the 1973 Endangered Species Act was enacted, the various stocks of salmon in the river were either classified as endangered or threatened. The states declared no fishing allowed so that the remaining salmon could spawn.

In 1977, the Columbia River Treaty Tribes -- Yakama, Umatilla, Warm Springs and Nez Perce -- created the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) to coordinate their fish management policies. Biologists working for the tribes estimated in the late 1980s that 16 percent of all the salmon in the river were being killed at the dams; some as they traveled to the ocean to grow and others upon their return to their natal stream to spawn.

More detrimental changes on the river also became evident, including warmer water temperatures in the lakes behind the dams and the loss of fish habitat due to logging, mining and other activities on the river. Salmon numbers declined drastically. By the early 1990s they only numbered in the mere thousands when the four CRITFC tribes proposed restoration plans for salmon in the Columbia River Basin to state and federal agencies. Tribal leaders and staff said it was time to change state hatchery polices and take the fish out of the concrete hatchery and place them in streams and the river where they had not been for years. They also wanted to restore the salmon's habitat to more-natural conditions.

Those proposals were met with skepticism. Some state and federal scientists insisted that mixing the hatchery fish with the wild fish would "dirty" the genetics of the wild fish. As they debated such points, the late Warm Springs leader, Delbert Frank Sr. wondered, "Are they going to study the salmon to death?"

Finally after almost two decades of planning and discussing and waiting, the four tribes began supplementing the salmon runs on the Columbia River. Fingerling fish (baby fish the size of a human small finger) were taken to the tribal fishery research centers. Once the salmon reached their juvenile stage they were placed in the upper reaches of the Columbia River Basin, where they stayed until Mother Nature told them it is time to go to the ocean. Once they returned they provided eggs that were incubated and fertilized, beginning the process again, and their progeny would be natural spawners in the river.

Today we know that the process is working -- salmon runs have rebounded in the Umatilla, Yakima and Clearwater rivers in the Northwest. There had been no salmon in the Yakima River for more than 30 years. Now there are many salmon there. Even sports fishers have congratulated the tribes for their work.

(bluefish recommends: Survival of Downstream Migration 2000 and Survival of Snake River Salmon & Steelhead 2004)

Celilo Village

After the death of the falls, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, with help from the Army Corps of Engineers, built 10 prefabricated barrack homes and four new homes while the tribal people waited for the Corps to fulfill its promise to build the longhouse so they could conduct their religious services. But that never happened, so in 1974 tribal people started to build the longhouse on their own, by hand. Bobby Begay, 42, was about 5 years old then. "We built it day-by-day, shingle-by-shingle, and eventually got it done," he said. Doing it all by hand, it took them almost a year to finish. "There were no chain saws, nails or staple guns back then either," Begay said. "They would hoist me and others by a rope to get the shingles to the men [on the roof]. I thought it was fun." He remembers his late grandmother, Maggie Jim preparing all the meals for all the workers. "She never let us go hungry and it was all good -- fish, roots, huckleberry pie."

When funding for the longhouse ran low Celilo people solicited townspeople and others who lived along the river. The money finally ran out before the top portion of the longhouse was completed. "They put tarp at the top to close it and later it was covered with roofing," recalled Chief Meanus.

In 2004 the head of the Army Corps of Engineers, General Carl Ames Strock, accepted an invitation to visit Celilo Village, and examined the dilapidated longhouse and run-down homes. Strock was told of the promises made long ago by the Army Corps of Engineers to build new homes and a longhouse for the village. He vowed to return to D.C. and get those promises fulfilled.

Later that year the Senate Select Committee on Indian Affairs directed the Army Corps of Engineers to build new homes and repair the longhouse at Celilo Village. Construction of the new 7,000-square-foot longhouse began in May 2005, and ended just two months later. Finally the Celilo longhouse held a celebration and ceremony on July 23 that attracted national media and an estimated 5,000 tribal and nontribal people.

Women from various tribes helped in the new state-of-the-art kitchen complete with stainless steel kitchen equipment including a walk-in freezer, refrigerator and commercial dishwasher. "It was hard to do everything by hand and lots of work in the old small kitchen area," said Lucy Begay Jim. Tribal and nontribal people shared their memories of the falls during dinner and it was a glorious day for the tribal members who had waited for so long for the federal government promises to come to fruition.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum