forum

library

tutorial

contact

As California Greens, Northwest Power Gains

by Daniel Jack ChasenNew West, December 20, 2009

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

As California Greens, Northwest Power Gainsby Daniel Jack ChasenNew West, December 20, 2009 |

There's an energy "butterfly effect": Buy a TV in L.A. and the next thing you know

we're developing more wind energy in the Columbia Gorge.

A couple of holiday seasons from now, plasma TVs may be hard to come by in L.A. and the rest of California. More likely, they'll be different from -- and possibly more expensive than -- the ones on sale today. And that, in a roundabout way, is one reason why the Northwest Power Planning and Conservation Council thinks this region can meet nearly all its energy needs with conservation for the next 20 years.

A couple of holiday seasons from now, plasma TVs may be hard to come by in L.A. and the rest of California. More likely, they'll be different from -- and possibly more expensive than -- the ones on sale today. And that, in a roundabout way, is one reason why the Northwest Power Planning and Conservation Council thinks this region can meet nearly all its energy needs with conservation for the next 20 years.

Last month, the California Energy Commission ruled that all TVs sold in the Golden State must be one-third more energy efficient starting in 2011, and 50 percent more energy efficient two years after that. This is not a trivial matter. Plasma TVs use more energy than conventional cathode-ray tube models or liquid crystal displays. In fact, it has been reported, "a 42-inch plasma set can consume more electricity than a full-size refrigerator."

The California Energy Commission estimates that TVs account for nearly 10 percent of the state's residential energy use, and the new TV regulations "would save enough power to supply 864,000 single-family homes," Marc Lifsher and Andrea Chang reported in the Los Angeles Times, "equivalent to the output of a 615-megawatt, gas-fired power plant, which would cost about $600 million to build."

What does that have to do with us? Plenty. The Northwest council's Draft Power Plan suggests that to a remarkable degree we can have our cake and eat it too. The draft plan "finds enough conservation to be available and cost-effective to meet the load growth of the region for the next 20 years. If developed aggressively, this conservation, combined with the region's past successful development of energy efficiency could constitute the future equivalent of the regional hydroelectric system; a river of energy efficiency that will complement and protect the regional heritage of a clean and affordable power supply."

This isn't simply visionary hope. It's based on a staggering amount of analytical work. Steven Weiss of the NW Energy Coalition says that the plan represents "one of the best modeling efforts in the country, if not the world."

The council's modelers have found that we can supply 85 percent of the region's energy needs over the next 20 years with conservation and increased efficiency, and the remaining 15 percent with renewables. Over the next five years, it predicts that the region can meet 58 percent of new demand through increased efficiency. The plan envisions no new coal-fired plants, and no nukes.

"Sources of potential savings are about 50 percent higher than in the Fifth Power Plan," the sixth draft plan explains. One would think the region had already plucked all the low-hanging conservation fruit. One would be wrong.

"The assessment [of potential efficiencies] is higher for two principle reasons," the draft explains: "First, the Council identified new sources of savings in areas not addressed in the Fifth Power Plan: consumer electronics, outdoor lighting, and the utility distribution system. Second, savings potential has increased significantly in the residential sector as a result of technology improvements and in the industrial sector as a result of a more detailed conservation assessment." The residential and consumer savings will happen only if private citizens make a wide range of choices. "In the residential sector, lifestyle choices affect demand," the draft plan notes. Those choices will depend on what's available and how much it costs.

That's where California's new TV regulation comes in. The Northwest represents way too small a market to drive technological innovation or force down prices. California, on the other hand, is big enough to push manufacturers in new directions. If California TVs have to use less energy, manufacturers will produce sets that meet the standards. Those same sets will be sold to consumers in the Northwest, where over time they'll help us meet future energy demands without new power plants.

Over the past quarter-century, the council's plans have institutionalized a faith in conservation and, increasingly, in renewable resources, transforming those ideas from a matter of morality to ones of cost-efficiency. They have also saved a lot of kilowatts. The group's first big choice was whether to save two moribund nuclear projects backed by the Washington Public Power Supply System, aka WPPSS. In 1983, council members decided to let the plants expire, and instead started committing the region to conservation. Since then, a council press release says, "the regional investment in energy efficiency reduced demand for electricity by 3,700 average megawatts and resulted in only about half as many new power plants being built as would have been without the efficiency improvements."

But people will not save all the energy that the draft plan foresees for the next five or 20 years unless their utilities make it worth their while. The plan assumes not only that consumers will use less electricity, but also that utilities will sell less. "In the past, regulators always rewarded utilities for getting bigger," Weiss notes. Now, the big question facing not only the companies but also regional planners is: "How are they going to make money by convincing people to use less?"

There's no single right answer. Different states and utilities have tried a variety of ways (PDF). You can "decouple" profits from the number of kilowatt-hours sold. (Washington decouples for gas, Idaho decouple for electricity, Montana will decouple for electricity, Oregon decouples for both.) You can provide financial incentives for a utility to conserve. (Washington does. Its neighbors don't.) You can provide incentives to shareholders. You can impose penalties on a utility that doesn't conserve. Finding mechanisms that work for specific regional utilities isn't a trivial matter. In fact, NW Energy Coalition Executive Director Sara Patton suggests that lack of agreed ways to reward utilities for pushing conservation is the biggest uncertainty facing the Power Plan. "We have to solve that one," she says.

The draft plan's scenarios cover a wide variety of possibilities. Economist Tom Karier, one of Washington's two representatives on the Power Planning Council, says council members felt it was only prudent to look at the possible removal of the lower Snake River dams, and at the possibility that Congress would impose either a range of carbon emission taxes or a cap-and-trade system for carbon emissions. What happens if the federal government breaches the dams to save threatened and endangered salmon? Not a whole lot. The modelers found that the average household's electric bill would rise by less than an additional 1 percent a year. Weiss says "it's pretty amazing that the cost impacts were barely noticeable."

"In normal times, we'd be jumping up and down," Weiss says.

But no one is jumping. These times aren't normal. Concern about climate change has moved front and center, and the NW Energy Coalition believes the council isn't doing enough to deal with it. "It's a plan that doesn't reduce carbon emissions at all," Weiss says. Instead, it "lets all the coal plants just go -- unless Congress acts."

Everybody "knows" that the Northwest generates power without releasing CO2, because we harness falling water instead of burning coal. Well, yes and no. We burn less coal than other regions -- and Seattle doesn't burn any at all -- but regionally, we get nearly one-quarter of our energy from coal. Puget Sound Energy, which supplies many of the region's most rapidly growing residential areas, is at more than 30 percent.

"Simply stabilizing CO2 emissions ignores the moral imperative to start cutting current emissions now," Patton and LeeAnne Beres wrote in a Seattle Times op-ed piece. "Washington, Oregon and Montana already have committed to 15 percent reductions by 2020, but the draft plan will not help the region achieve these emission-reduction goals." They argued that the draft plan "is good, as far as it goes. But we must go farther, faster, and commit to phasing out dirty coal plants."

The council explains its mission as: "develop[ing] a 20-year electric power plan that will guarantee adequate and reliable energy at the lowest economic and environmental cost; ... develop[ing] a program to protect and rebuild fish and wildlife populations affected by hydropower development in the Columbia River Basin," and public involvement. Even as the nations meet in Copenhagen, there's nothing about combating climate change.

Nevertheless, they could probably do it if they wanted to. Weiss suggests that the real reason for punting on the demise of coal may be less structural than political. There is no reason why council decisions can't be made by narrow majorities, but the group has never operated that way. Most decisions reflect a consensus. On coal, the chance of getting unanimity is close to zero. The chance of winding up with a 4-4 split is high. If some members forced the group down that road, Weiss says, "it could destroy the council."

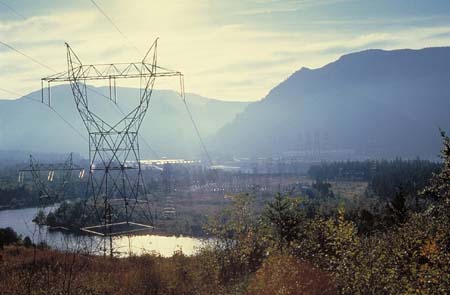

But no one sees new coal plants on the horizon. Beyond conservation, we're primarily talking wind. At this point, Karier says, bringing in new wind resources is easy, because the hydro system is flexible enough to take up the slack when the wind doesn't blow. Down the road, though, the wind load will exhaust the ability of the hydro system to back it up. In the short term, natural gas will take up the slack. In the long term, the council looks toward a "smart grid," and storage in batteries, or through a system of pumping water back up above the dams to be used when needed.

For now, there's enough transmission to or near the wind sites that are being developed. Later, as the obvious sites in the Columbia Gorge and other nearby locations are filled, the region will look farther east to Montana, which has greater wind potential anyway. Then, the new kilowatts won't be available without new transmission lines -- with all the issues of financing and siting that building transmission lines will inevitably raise. That won't be a problem anytime soon, Karier says, unless California starts competing for power from the closer sites -- which it certainly will.

The Golden State has decided to increase its renewable portfolio from 20 percent to 33 1/3 percent. That increase adds up to more electricity than the Northwest's total use. California will buy the additional juice wherever it can. A kilowatt from the Columbia Gorge will work just as well as one from Altamont Pass. If that wind energy from the Gorge starts flowing down the coast to San Francisco and L.A., the Northwest will need new east-west lines sooner, rather than later.

That means big investments, and, probably, big battles over locating rights-of-way. The greening of California may, therefore, shape Northwest decision-making in more ways than one.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum