forum

library

tutorial

contact

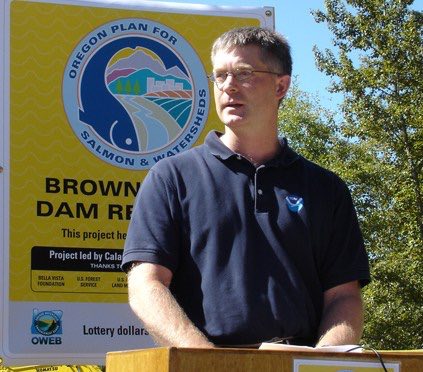

Columbia Basin Bulletin Q&A with Barry Thom,

Director of the West Coast Region of NOAA Fisheries

by Staff

Columbia Basin Bulletin, March 17, 2022

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Columbia Basin Bulletin Q&A with Barry Thom,

by Staff

|

Barry Thom leads the West Coast Region of NOAA Fisheries and is responsible for implementing NOAA Fisheries mandates under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, Endangered Species Act, and Marine Mammal Protection Act along the U.S. West Coast from Washington to California.

Barry Thom leads the West Coast Region of NOAA Fisheries and is responsible for implementing NOAA Fisheries mandates under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, Endangered Species Act, and Marine Mammal Protection Act along the U.S. West Coast from Washington to California.

He works extensively on management of groundfish, salmon, tuna and other fisheries both along the West Coast and Internationally. Barry also leads efforts to protect and recover endangered species such as Southern Resident Killer whales, Pacific salmon and white abalone. He focuses his efforts on collaborative solutions, including convening the Columbia Basin Partnership, a collaborative process to establish long-term goals for Columbia Basin salmon and steelhead, and serves as co-lead of the Puget Sound Federal Task Force. He will soon be leaving NOAA Fisheries to become Executive Director of the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission.

CBB: Working for 21 years in NOAA's Northwest and West Coast offices, you have had a front row seat to Northwest salmon recovery and Columbia/Snake river basin salmon recovery efforts. How would you describe the state of regional salmon recovery today?

THOM: I would highlight three key areas. First, we know much more about the species and what affects them, we invested in science and that information has helped us target efforts. We know more about the impacts such as where habitat loss is occurring, the impacts of toxics, and how to improve passage and survival. Second, the problem has gotten more difficult. Whether it is climate change, the pace of development, or other pressures, we have not been able to keep up with the pace of impacts. Lastly, I would highlight how important it is to uphold the Treaties that the government signed with many tribal nations. More and more people recognize the importance of the treaties and how important it is to recover these stocks to healthy abundant levels. It will take all of us to make that happen.

CBB: How would you describe NOAA Fisheries' role in Columbia Basin salmon recovery?

THOM: NOAA has several roles as it relates to salmon recovery. We guide efforts through the development of robust science and recovery plans. We have a role as a regulator under the ESA to help protect the species and their habitats. We fund many habitat and hatchery activities in the basin. Most importantly we have a role to keep everyone focused on recovery. People say, NOAA Fisheries hasn't recovered any salmon. The reality is we cannot do it alone. It will take societal change and we need everyone's help to get there.

CBB: Thirteen species of Columbia River basin salmon and steelhead were listed as threatened or endangered in the 1990s. What in your mind are the main reasons not a single population to date has been recovered and de-listed for the last 25 years?

THOM: It is true that we have not delisted any salmon or steelhead stocks on the West Coast. However, we have made important progress in a lot of different areas. First, we have prevented the extinction of several stocks, including Snake River sockeye. They would not exist on the landscape today but for the hard work of many. Second, we have addressed many factors limiting recovery -- we have reformed hatcheries, limited harvest, made substantial improvements in the hydrosystem and made some notable gains in habitat protection in forested areas. Look at Oregon Coast coho, for example. We addressed harvest and hatcheries early on and are making progress on habitat. Hydropower is not much of an issue for them. The fish are showing improved resiliency based on how they came through this most recent downturn in the ocean. They did not fall to the low points we have seen in the past and they have rebounded quickly. If we can make some progress on low-gradient floodplain habitat and certainty on forest land protection I could envision delisting in the near future. Contrast that with Snake River spring Chinook. We've also limited harvest, improved hatchery management, improved survival through the hydrosystem and are even starting to better address pinniped predation. However, the salmon are at levels about where they were when they were listed under the ESA. Clearly more is needed to improve their resilience. The Columbia Basin Partnership found that to have the really robust and resilient salmon populations people want, we have to do everything we can think of. It's natural to do the easier things first but now we have to step up and put everything on the table.

CBB: What do you see as some of the main successes in basin salmon recovery over the last 20 years?

THOM: I would highlight several successes. We know so much more about their life histories and what the fish need. This has really changed where and how we focus our collective efforts. Our habitat restoration techniques are much improved from when I started my career. We now focus on re-establishment of natural habitat-forming processes. There is no question that we have substantially improved survival through the hydrosystem. There are many views on whether it is enough, but we have come a long way. We have some of the best fish passage expertise in the world and salmon can routinely access more habitat than at any other time in the past 50 years. We also know much more about the impact of toxics and water quality. Look at the research that is coming out on 6PPD-quinone, its impacts and what we can do about it. It is troubling, but at least we now can develop some solutions. All of these have taken years of research and a willingness to make the necessary changes.

CBB: You have been a strenuous proponent of collaboration as one of keys to breaking the gridlock in basin salmon recovery. You launched the “situation assessment" in 2012 that eventually led to the Columbia Basin Partnership, and then the current Columbia Basin Collaborative. How would you describe the benefits of these efforts and the status of collaboration? Are you hopeful?

THOM: I am hopeful. It is not enough to know what's wrong in the system -- we actually need people to agree how to fix it. The Columbia Basin Partnership was a step in that direction. One of the most valuable results of the CBP are the relationships we built and cemented, that I am confident will last and will foster progress and solutions. The Partnership created a new vision of what we all want to see in terms of a vibrant Columbia River that includes robust fish runs, helps address the needs of the Tribes and also maintains the economy and broader ecosystem. We all need to keep that collaboration going to the point of taking action. I am hopeful because the potential productivity of the Columbia basin is enormous and people want a better future for the basin.

CBB: Last year Idaho U.S. Rep. Mike Simpson released his “Columbia Basin Initiative" for regional discussion, which of course calls for breaching lower Snake River dams after mitigating for the economic benefits from the dams and reservoirs. The premise is that Snake River wild salmon and steelhead are on the brink of extinction and such a move may be the fishes' only hope for survival. What is your view of Simpson's plan and its contribution to regional debate and consensus?

THOM: There are a lot of discussions going on in the basin right now and a lot of ideas floating around. I welcome Congressman Simpson's leadership in putting something out on the table and welcome anyone else to get their ideas out there. The Columbia Basin Partnership Task force report also has a good list of ideas. The challenge now becomes how to get reasonable folks to sit down, collaborate, and agree on a path forward. It is not an easy discussion, but the challenges are not going to get any easier if the stocks continue to decline, climate continues to change and the pace of development quickens.

CBB: What role is climate change now playing in NOAA's work to assess the status and future of basin salmonid stocks? What's your view on how our warming waters will impact Northwest salmon and steelhead?

THOM: Climate change and its impact on salmon stocks is central to our work in both the science and management sides of the house. We have done a lot of work on the implications of climate change and we have a picture of where we need to go. We know salmon face changes across their life cycle. However, the ocean is changing in ways we are just starting to understand. We know the direct effects, as we see it in our salmon returns and changes in the ecosystem. What we don't know are the causal linkages or whether we can do anything about it. Our solutions need to focus on maintaining the resiliency of salmon and steelhead in the freshwater environment. That is a place where we can take action and we know what actions can maintain and improve resilience. They include coldwater refugia in their migration corridors, riparian habitat protections to maintain stream temperatures and adequate spawning and rearing habitat. Salmon have tremendous adaptive capacity, but we need to give them that space to adapt.

CBB: One thing I have noticed over the years is that while great fisheries research is going on in the basin, with plenty of answers about what's happening to the fish, it doesn't always interest policymakers or get translated into effective policies. Do you have any thoughts on improving links between science and policy?

THOM: I have actually seen many instances where new science has driven change in management over my career. We have strengthened riparian protections, water quality standards, hatchery practices, fish passage criteria and many other areas related to salmon recovery and fisheries management. What I do see as a challenge is how to more effectively achieve management change. There are many people that benefit from the status quo on any given issue and we need to do a better job of educating people on the benefits of shifting that status quo and achieving buy-in on a new paradigm. People, especially elected officials, need to see how their interests or their constituents' interests have been addressed. It is why I have focused more on collaboration and communication efforts later in my career.

Q: With its reviews of Hatchery Genetic Management Plans, NOAA is at the center of the wild vs. hatchery debate across the Northwest. How would you explain NOAA's approach to wild vs. hatchery, and supplementation?

THOM: The management of hatchery fish in the system is an area where we have seen success, but it will take continued management and implementation. First I would highlight that hatcheries serve multiple purposes. They can serve a conservation function and prevent extinctions, they can serve a mitigation function to support fisheries where we have lost passage or habitat, and they can serve a true production function by powering fisheries (and even Killer Whales) in-river and off our coast. NOAA has a tough job to balance all of that with the need to achieve protection and recovery of ESA listed stocks. Our approach has been to make sure we achieve the ESA requirements we need, while allowing as much production as we can. In many cases we recognize that an experimental and adaptive approach may be the best way to allow for transition of programs while also continually testing assumptions and improving the information we do have. I think we have been pretty successful to date and recognize that it will be continually evolving.

CBB: Southern Resident Killer Whales are now intimately tied to Northwest salmon recovery. What do you see as the future for this struggling, listed population?

THOM: With the continued declining status of these iconic whales, NOAA has shifted its focus from one of conducting research to determine what might be impacting these whales to one of carrying out actions that can improve their status and adaptively managing as we go along. While we don't have all the answers, we do know that they are food limited, sensitive to noise in the environment, susceptible to ship strikes and have high toxin loads. There are many actions we can take and are taking to address those threats and give them the greatest chance at recovery. However, if society wants to keep these whales on the landscape, we need to make room for them. It is not enough just to reduce impacts a little bit. They are affected by the same factors of degraded habitat that affect salmon. We need to actually give them what they need.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum