forum

library

tutorial

contact

Fuel Barges Running Afoul

on the Columbia River

by Scott LearnThe Oregonian, July 21, 2009

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Fuel Barges Running Afoul

by Scott Learn |

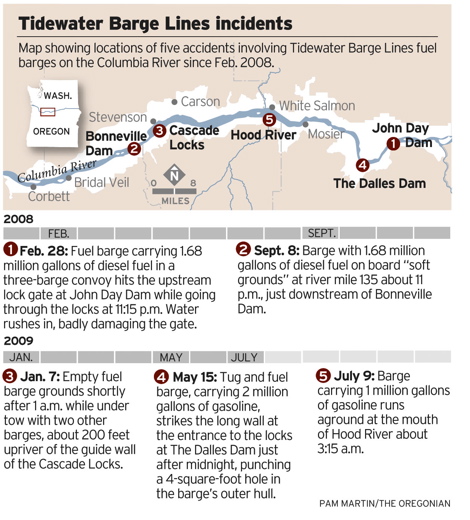

Fuel barges from Tidewater Barge Lines have been involved in five nighttime incidents on the Columbia River since February 2008, including two accidents involving dam locks and three groundings at the river bottom.

Fuel barges from Tidewater Barge Lines have been involved in five nighttime incidents on the Columbia River since February 2008, including two accidents involving dam locks and three groundings at the river bottom.

The incidents, most recently a 2-day grounding of a Tidewater fuel barge earlier this month near Hood River, did not result in any fuel leaks.

But the number of incidents is up significantly over prior years, U.S. Coast Guard records indicate. The most dramatic: A barge, loaded with gasoline, ran into a wall at The Dalles Dam in May, putting a 4-square-foot gash in its outer hull.

And the federal agencies involved, including the Coast Guard, are giving scant details, citing the confidentiality of ongoing investigations that have now reached up to 16 months long. Combined, the barges were carrying more than 6 million gallons of gasoline and diesel, a potential threat to the Columbia's sensitive environment and vaunted salmon runs.

Tidewater, based in Vancouver, Wash., is the main transporter of gasoline and diesel fuel up the Columbia and Snake rivers. The company says its safety record includes no tank barge fuel leaks of any size in nearly 16 years, despite about 400 fuel tanker round trips a year.

Washington and Oregon regulators say Tidewater works well with them on fuel spill prevention drills and response. Coast Guard records indicate tank barge incident rates, adjusted for river traffic, are much higher on other big shipping rivers, including the Ohio, Mississippi and Illinois.

And Washington regulators, who operate the Northwest's most robust oil and fuel spill program, say the risk of a massive fuel leak in the Columbia-Snake system is low.

The Columbia's generally soft bottom and lack of rocks, rough tides and steep ledges help reduce the risk, said Chip Boothe, spill prevention manager for the Washington Department of Ecology.

So does Tidewater's commitment to double-hulled fuel barges with empty void spaces designed to absorb collisions, Boothe said, and the slow speeds tugs use when they push barges near dams. The barges have up to 12 separate fuel tanks -- not just one big one -- also cutting the risk of a huge spill.

But the potential environmental damage in the event of a leak or spill is high.

But the potential environmental damage in the event of a leak or spill is high.

High winds, fog and river traffic that ranges from barges to fishing boats to kiteboarders can make it tricky to navigate the fuel barges, typically twice the width of standard barges.

Were a large spill to happen, Boothe said, "it would be very difficult to contain it in a fast moving river."

Gasoline and diesel don't stick around like crude oil, rarely transported into the Columbia.

Yet highly flammable gasoline is difficult to contain, and diesel lasts longer in the environment than gasoline. Both fuels are potentially toxic to fish and wildlife.

All of Tidewater's incidents occurred in the dark, when regulators say navigation is tougher. Otherwise, it's difficult to find common denominators between incidents, in part because of the minimal details given by the federal agencies involved.

The U.S. Coast Guard oversees tank barge operations on Columbia. It refuses to release names of anyone involved in the incidents, from witnesses to tug masters to pilots, citing privacy exemptions in the federal Freedom of Information Act.

Dennis McVicker, Tidewater's president and CEO, said he couldn't discuss the dam incidents or the most recent grounding in detail because Coast Guard investigations are still underway.

But he said key crew members involved in the different incidents were not the same. The company is awaiting drug and alcohol tests in the most recent accident, he said, but drugs and alcohol were not factors in the four other incidents.

Crew member experience and river conditions, including darkness at the time of the incidents, also do not appear to be factors, McVicker said.

Tidewater's last spill came in October 1993, when 3,295 gallons of diesel spilled from a barge docked at the company's Snake River Terminal in Pasco, Wash., McVicker said.

Since then, the company has largely converted to double-hulled barges ahead of a federal schedule to switch over by 2015, he said, and has helped deploy spill containment equipment at 10 spots along the river.

The company's extensive spill training with federal and state regulators lowers spill risks, he said. It last participated in a "worst case" drill on March 31.

"We understand that the community has very high expectations," McVicker said. "We have spent a lot of money, a lot of time and a lot of effort to make sure the program works. Really, it is by design that we do not have spills."

The Coast Guard also declined to discuss details of the most significant incidents -- the dam incidents and the grounding earlier this month. The agency has not yet responded to a records request last week by The Oregonian for details of both the open and closed investigations.

Petroleum products are the most common goods moving up the Columbia and the second most common commodity carried in either direction, after grain and other food.

But Michael St. Louis, senior investigations officer for the Coast Guard's Portland sector, said Columbia River fuel barge incidents tend to be "minor" in terms of environmental risk. "A severe environmental impact is not likely," St. Louis said.

The Coast Guard is still investigating the first incident in February 2008 at the locks of the John Day Dam, 25 miles east of The Dalles.

On that night, a Tidewater fuel barge carrying 1.68 million gallons of diesel fuel was part of a three-barge convoy that included two empty grain barges.

The grain barges apparently hit the upstream lock gate, badly damaging the gate and temporarily stranding the barges in the lock.

The Army Corps of Engineers, which operates the Columbia dams, says its own investigation into the John Day incident is complete, and the cost to fix the gate totaled more than $4 million.

But the agency refused to release the investigation, which it says includes dam schematics, citing homeland security concerns.

Seven months later, in September 2008, a Tidewater fuel barge with 1.68 million gallons of diesel "soft-grounded" in the Columbia downstream of Bonneville Dam.

Then in January 2009, an empty Tidewater fuel barge touched bottom near Cascade Locks in high winds.

McVicker described the January grounding as a brief "touch and go" that illustrates how Tidewater reports even minor incidents.

But based on that grounding, the company decided to sideline its remaining three single hull fuel barges, he said.

So far this year, its eight double-hull fuel barges -- with a distance of at least three feet between the outer hull and the fuel tanks -- have carried 99 percent of the fuel on the river, McVicker said.

In May a tug and fuel barge carrying 2 million gallons of gasoline struck a wall at the entrance to The Dalles Dam locks.

The collision knocked a 4-foot by 4-foot hole in the barge's bow. But there was at least 25 feet of empty space between the hole and the fuel tank, McVicker said, providing a considerable safety margin.

Then, on July 9, a loaded Tidewater fuel barge grounded on an uncharted sand bar near Hood River. The barge was stuck for about 36 hours, requiring transfer of 500,000 gallons of gasoline to another tanker before it could be refloated.

The Corps says the barge was outside the federal navigation channel. The Coast Guard says the vessel was in what should have been safe water, with the ship drawing about 12 feet of water at a point where depths were charted at 30 feet.

Nationwide, fuel leaks from tank barges are uncommon but not unheard of. Since 2001, a Coast Guard database of completed investigations has noted eight leaks of 10,000 gallons or more, none in the Columbia system.

The most recent leaks involved barges grounding on rocks or transferring fuel.

Headquarters: Vancouver, Wash.

Established: 1932

Employees: 300

Fleet: 17 tugboats and 188 barges, including eight double-hulled fuel barges and three single-hulled fuel barges

Fuel terminals: Three, one each in Pasco, Wash.; Clarkston, Wash.; and Umatilla, OR

River round trips by fuel barges: About 400 a year

Other items barged: Grain, wood products, municipal garbage, containerized freight

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum