forum

library

tutorial

contact

Amid a Battle Over Snake River Dams,

a Look at How the Salmon are Doing

by Matthew Weaver

Capital Press, May 18, 2023

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Amid a Battle Over Snake River Dams,

by Matthew Weaver

|

For every 100 young chinook and steelhead that head downstream

and past the four dams every spring, about 75 survive.

The vast majority of salmon are getting up, over, around and through the four lower Snake River dams even as legal challenges and political battles swirl around them, according to the federal agency in charge of monitoring fish health.

The vast majority of salmon are getting up, over, around and through the four lower Snake River dams even as legal challenges and political battles swirl around them, according to the federal agency in charge of monitoring fish health.

For every 100 young chinook and steelhead that head downstream and past the four dams every spring, about 75 survive.

"That's pretty good," said Ritchie Graves, Columbia Hydropower Branch chief for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "In a lot of river systems, that would be something they would shoot for."

For each of the four dams, NOAA maintains a separate survival standard for juvenile salmon heading downstream. The agency wants 96% survival for yearling chinook and steelhead, and 93% for "subyearling" chinook less than a year old.

The dams are achieving those performance standards, Graves said.

For adult fish swimming upstream, the survival rate is above 90%.

How many fish survive the trek past Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite dams is at the core of the decades-long conflict over them.

Environmental groups and Native American tribes want the dams removed as a way to increase salmon populations.

Farmers and other stakeholders support salmon recovery, but say dam breaching isn't a "silver bullet" that will automatically lead to more fish.

In the middle are agencies such as NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service, referred to as NOAA Fisheries, which monitors the dams' impact on fish, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which operates the dams.

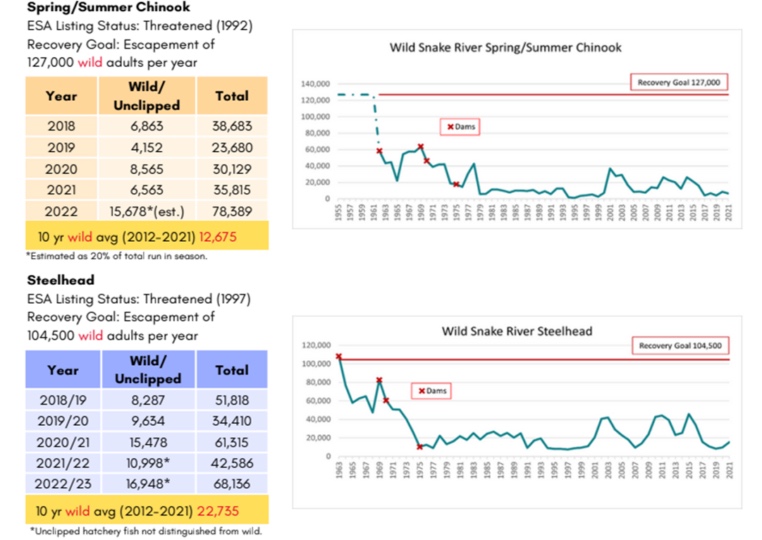

Of 12 distinct populations of fish in the interior Columbia Basin, seven are protected under the Endangered Species Act and five are unlisted.

"Clearly, the fish aren't recovered, they're still listed," Graves said. "The good news is, we haven't lost any populations in 25 to 30 years of listing, either."

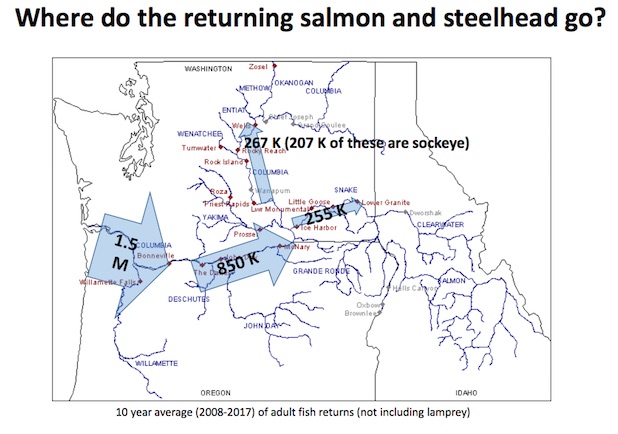

How fish move

In the last five years, the number of fish passing upstream past Lower Granite Dam each year averaged:

Adults swim upstream, spawn in the river systems above the dams, and their offspring migrate downstream at varying times to the Pacific Ocean. They then live in the open ocean for several years.

To get downstream, the juvenile fish either swim or ride the river flow near the surface of the water, said Michael Milstein, a NOAA spokesman.

They get past the dams several ways. The dams are built so that spill gates open from the bottom up, so the fish can dive deep to find their way through.

They can also get past the dams through spillway weirs, which allow them to "ride" the water as it passes over the spillway.

The spillways greatly reduce the chances the juvenile fish will pass through the dams' turbines, Millstein said. Turbines operate depending on the river flow and are screened at some dams to prevent fish from entering.

For adult fish returning from the ocean, the passage is less stressful.

"Upstream is actually easier," Graves said. At the dams, the fish swim up the gradual incline of the ladder that spirals from the downstream side of the dam over to the upstream side.

Elsewhere in the U.S., fish ladders "often perform much worse," he said.

"The fish ladders in the Columbia River Basin are as good as it gets," he said.

"Salmon are so driven to get to where they want to go, if you give them an opportunity, they will take it," he said.

The salmon die after spawning. Some steelhead attempt to return to the ocean and then make another run to spawn again, Graves said.

Migration timing

Fish populations are typically named for the time of year they swim upstream as adults, Graves said.

Fall chinook spawn in the autumn and the subyearlings emerge in March and April. They migrate downstream to the ocean in late May through July.

Spring chinook and steelhead can spend up to three years in fresh water before migrating out to the ocean as juveniles.

NOAA biologists believe adult upstream migration hasn't changed much because of the dams. They might be slightly delayed, but they're also not fighting as strong a current as before the dams were constructed.

"It kind of washes out," Graves said.

On the other hand, the dams create reservoirs, which slows the water flow and increases exposure to predators.

Swimming downstream, juveniles face a bit of a "headwind" the whole way, Graves said.

"It makes it a little harder, it costs some more energy than it did historically," he said of the juveniles. "They're probably delayed pretty substantially compared to historical conditions."

Latent or delayed mortality is the biggest unanswered question surrounding the salmon and the dams, Milstein said.

That's when juvenile fish die later because of the stress they experience getting past the dams. If that happens, it's not reflected in NOAA's fish passage numbers.

"The problem is that delayed mortality is difficult to measure because it occurs in the ocean, and different ways of estimating it lead to different results," he said.

NOAA is looking for better ways to measure delayed mortality, Graves said.

"It's devilishly hard," he said. "The science is challenging on this."

Zero mortality, or 100% survival, is not possible, he said. "High" or "significant" juvenile mortality would still occur naturally.

Predators such as sea lions and orcas are primarily interested in adult salmon, Milstein said. The biggest predators for juvenile fish include birds such as gulls, terns and cormorants and non-native game fish such as bass and walleye.

"It's a long and dangerous trip for a small fish, and there are many hungry mouths along the way," Milstein said.

Ocean warming

Ocean warming due to climate change may be the biggest factor of all, Milstein said.

"Salmon survival in the ocean is closely related to ocean temperatures, and as the temperatures increase, survival declines," he said.

Overall, the oceans have warmed 1.5 degrees since 1901. That is not the main issue for salmon, because the ocean does not warm the same amount everywhere, Milstein said.

In addition, the Pacific Ocean has always gone through warm and cool phases because of a 20- to 30-year cycle called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. Cool phases are more productive and salmon grow faster and survive at higher numbers, Milstein said. Warm phases tend to be associated with downturns in salmon returns.

Marine heatwaves are a new factor, beginning with an event referred to as "the blob" in 2014, which increased Pacific Ocean temperatures "beyond anything we have seen before," Milstein said. Marine heatwaves occur when ocean temperatures are much higher than usual for an extended period of time.

"There have been a few more since then, and this pushes the ocean into a warmer state that is less productive for salmon," Milstein said. "Climate change is gradually increasing the underlying temperature and marine heatwaves are riding on top of that."

The whole picture

The whole picture

NOAA officials are "confident" that if the dams were breached, survival rates would improve for juveniles swimming downstream and adults swimming upstream, Graves said.

Mortality would probably be cut in half , he estimated.

But to have thriving populations, all factors beyond the dams must also be considered, he said.

"It's just a really complicated, intertwined ball of stuff," Graves said.

He believes pro-breaching factions gloss over the other aspects of salmon population recovery management, as listed in a 2022 report from NOAA Fisheries, which included habitat restoration and the impacts of predators, in addition to breaching.

"You're not going to be able to do any one thing and reach those goals, you need to do all of that," Graves said. "Quit trying to pick and choose your favorite sacred cow."

What environmentalists say

"The science is pretty clear: Restoring the lower Snake River and breaching the four dams there is an essential centerpiece action if we're going to avoid salmon extinction and restore healthy populations," said Todd True, senior attorney at Earthjustice, citing NOAA's report. "We need to get on with that as soon as we can."

The energy, transportation and irrigation services the dams provide also must be replaced, True said.

"We can do that, but we have to get started, and the people who don't even want to talk about (breaching) have to get on board with finding a way forward," he said.

The nonprofit environmental law organization represents conservation and fishing groups in long-running federal litigation against NOAA Fisheries in Portland. The case is currently stayed to allow for mediation led by the White House Council on Environmental Quality. The stay will end Aug. 31.

The next steps are "unfolding" within the mediation, True said.

"I can't tell you where those steps will land," he said.

What the tribes say

The 60 Tribal Nations of the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians support dam removal and a $33.5 billion proposal by Rep. Mike Simpson, R-Idaho, that calls for dam breaching and replacing the benefits the dams provide.

"Salmon -- the icon of the Pacific Northwest -- are facing an extinction crisis, and need a restored lower Snake River," Nez Perce Tribe Chairman Samuel Penney said in 2022. "The subsidized services provided by the four dams that have turned the Snake into a lake can be replaced and addressed, and in doing so we will be charting a smarter, better future for the Northwest and the nation."

What agriculture says

What agriculture says

"When you look holistically at this issue, dam breaching does not make sense," said Heather Stebbings, executive director of the Pacific Northwest Waterways Association. The association supports river navigation, energy production and transmission, trade and economic development that the dams support.

Agriculture supports further improvements to the dams and all other salmon recovery efforts, she said.

"The one thing we don't support is dam breaching," she said, citing the high costs and loss of transportation options for farmers. Currently, much of the wheat crop goes downriver in barges that get past the dams via locks. Without the locks, much of the Snake and Columbia River system would become impassable for barges.

The infrastructure's not in place to switch from barge to rail and truck, she said. Tugboat companies would lose upriver business and communities would see significant increases in their power rates and possible energy brownouts.

The four dams have the capacity to produce 3,033 megawatts of power but typically average about 900 megawatts annually, enough to power 716,400 homes, according to the Corps. One megawatt can power 796 homes.

Dependence on diesel would increase by 5 million gallons each year as more trucks and trains shuttled from eastern Washington and Idaho to the ocean ports downstream. Carbon dioxide and other emissions would also dramatically increase.

"We really wanted this mediation to focus more on the things we can all agree on for the fish, rather than myopically focus on breaching the Snake River dams," Stebbings said. "If they could come to the table ... they would realize there's a lot of good we can do together in terms of bringing federal dollars back to our region for the projects on the ground that will bring fish back."

That hasn't happened, she said.

"I do not feel that all stakeholders have been given the same consideration in the process, no," she said.

The conversation

Fish survival at the Snake River dams is better than most systems in the nation and world, NOAA's Graves said.

But he wonders: Is it good enough? Does more need to be done?

"That's the active question that causes lawsuits and discussions," he said.

Graves welcomes the conversation.

"We should be talking to each other about, if this isn't working, what else needs to be done?" he said. "Where's the best place to invest our effort as the Northwest region? If we're serious about recovery, what are we going to do about that?"

Related Pages:

Salmon Science Dispute Rages by Eric Barker, Lewiston Tribune, 1/15/21

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum