forum

library

tutorial

contact

Washington 'State of Salmon' Report:

Seven ESA-Listed Populations Showing No Recovery Progress

by Staff

Columbia Basin Bulletin, January 19, 2017

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Washington 'State of Salmon' Report:

by Staff

|

In most of Washington State salmon recovery goals are not being met.

In most of Washington State salmon recovery goals are not being met.

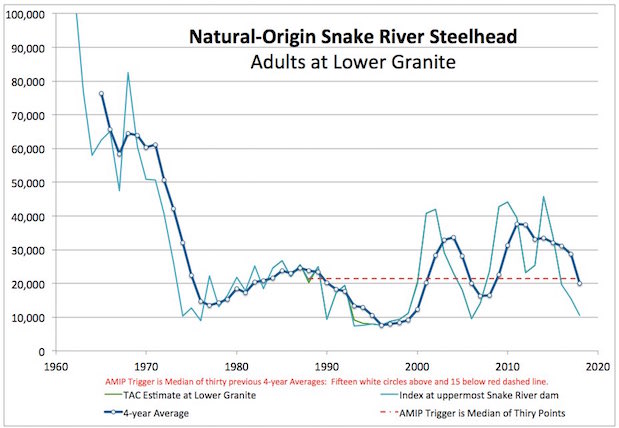

Of the 33 genetically distinct populations of salmon and steelhead found within the borders of the state, 15 are listed as threatened or endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act and seven of those populations are not making progress or are declining relative to recovery goals, according to an annual report from Washington Gov. Jay Inslee's salmon recovery office.

"State of Salmon in Watersheds,” released this month, outlines Washington's progress in listed salmon and steelhead recovery efforts. The report concludes that continued investment at the state, federal and local levels is required if some of the most threatened and endangered species are to be saved.

The full report can be found here. An accompanying interactive website is here. According to a press release from the governor's office, the website provides live data from around the state and offers interactive maps to help visitors learn about salmon recovery efforts in their communities.

"Washington State has been investing in salmon recovery for nearly two decades, and we are seeing some results,” Inslee said. "But we still have many challenges ahead, such as population growth and climate change. Salmon are a crucial component of our economy. Families depend on them for food and jobs. They are crucial to our identity as Washingtonians. We can't give up on salmon recovery until they are taken off the endangered species list. Salmon are ours to save.”

Some of the more dire findings from the report are:

(See CBB, February 27, 2015, New Report Documents Washington State's Salmon Recovery Efforts)

The 2016 report says:

There is some good news, especially in habitat restoration and hatchery reform, according to the report.

Today's hatcheries operate to ensure they don't harm wild salmon and steelhead, the report says. Some 88 percent of the state's hatchery programs meet scientific recommendations to ensure conservation of wild salmon and steelhead, compared with only 18 percent of hatcheries meeting those recommendations in 1998.

One example is a Tulalip Tribes project that restored tidal flow to 350 acres on the Snohomish River, providing unrestricted fish access to 16 miles of upstream spawning and rearing habitat. Another example is a WDFW project that is setting back a mile-long coastal dike to restore the natural tidal flow of Skagit Bay to 131 acres.

"When we fix our rivers and watersheds, we not only help salmon, we help ourselves,” Cottingham said, pointing to the benefits of restoration in local communities. "We get cleaner air and water, less flood damage, more opportunities for recreation and other natural resource-based industries and communities that are more resilient in the face of warming temperatures, drought, forest fires and sea level rise.”

The report's recommendations for what needs to be changed to improve salmon recovery includes better integrating harvest, hatchery, hydropower and habitat actions; fully funding regional recovery organizations and increasing state agency resources to meet salmon recovery commitments; restoring access to spawning and rearing habitat; and increasing monitoring of fish and habitat to fill in data gaps.

"It took more than 150 years to bring salmon to the brink of extinction; it may take just as long to bring them all the way back,” Cottingham said. "But every bit of progress we make today delivers long-lasting benefits for all. Now is the time to reinvest and recommit to salmon recovery in our state.”

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum