forum

library

tutorial

contact

When the Terminal's Done,

Who Will Supply the Grain?

by Erik OlsonThe Daily News, November 28, 2009

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

When the Terminal's Done,

by Erik Olson |

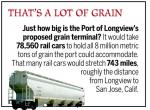

Think about the scope of the Port of Longview's latest development this way: The new grain terminal can export enough wheat, corn, soybeans in one year to fill a line of rail cars stretch 743 miles, roughly the distance from Longview to San Francisco.

Think about the scope of the Port of Longview's latest development this way: The new grain terminal can export enough wheat, corn, soybeans in one year to fill a line of rail cars stretch 743 miles, roughly the distance from Longview to San Francisco.

Longshoremen could load and unload the equivalent weight of 1 million African elephants in a year -- 8 million metric tons a year.

The grain terminal, which Portland-based EGT Development started building this summer, could by itself handle the demand for soybean imports into Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand for a year. If the Longview terminal were built a few hundred miles north, it could have handled all the barley exported from Canada for 10 months of 2008, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

In a word, it's big, and the $200 million terminal could have a big impact on the community by creating up to 80 permanent jobs, reducing local property taxes and making Longview a big player in the multi-billion dollar grain industry when it comes on line in 2011, according to the developers. Company officials say the Longview terminal will capture some grain from the American heartland now shipped to Asia through New Orleans and the Panama Canal.

But other Columbia River terminal operators wonder if Longview's added capacity will come out of their hides -- in effect, that the pie won't grow but just be divided into smaller pieces. The river already boasts two terminals in Kalama, one in Vancouver and one in Portland, and together they already handle 70 percent of U.S. wheat exports.

"There's sufficient capacity in the Pacific Northwest already to handle what demand we already have," said Tom Hammond, president of Columbia Grain Inc., which operates a terminal at the Port of Portland.

For the few years, the grain business will likely be spread amongst the Columbia River ports with little net gain, he said.

For the few years, the grain business will likely be spread amongst the Columbia River ports with little net gain, he said.

"They've added a lot more capacity than there will be growth" in grain demand, he added.

Through September, grain exports at Kalama Export and United Harvest at the Port of Kalama were down nearly 35 percent from a brisk 2008, and other Columbia River ports have seen similar declines, according to the Pacific Maritime Association.

Farmers were hustling to take advantage of last year's weak dollar and get their product to market, so the dip this year was expected, Port of Kalama officials said.

Farmers in Washington's bread basket, the sprawling fields east of the Cascades, export 85 percent of their wheat and barley, and the existing Columbia River port terminals are sufficient to handle that, said Tom Mick, corporate executive officer for the Washington Grain Commission.

However, the EGT is planning to export other grains, including corn and soybeans, grown mostly in the Midwestern states, Mick said. The added capacity would be good for Washington growers and could attract more export business to the Pacific Northwest in the long term, he said.

EGT officials are negotiating with grain producers and won't get into specifics about where the company will get its grain, EGT spokeswoman Deb Seidel said. Generally, the grain could come as far north as Canada and as far east as Iowa, she said.

EGT is a partnership among St. Louis-based grain giant Bunge North America, Japan-based Itochu Corp. and Korean shipper STX Pan Ocean. China is the company's biggest target because of its booming population, but EGT also is seeking customers in Japan and Korea, Seidel said.

Larry Clarke, EGT's corporate executive officer, will spend much of 2009 in Asia looking for the best markets for U.S. grain, he said recently.

Over the next 10 years, China's demand for soybeans will increase by 21.6 million metric tons -- about 80 percent of the growth in worldwide demand for exports, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Bunge, EGT's majority partner, already has the largest grain storage capacity in the Mississippi River region. About 60 percent of North American grain is shipped through New Orleans and other Gulf of Mexico ports to Europe, Africa and Asia.

The Longview facility is likely to compete with Gulf Coast ports in grain-producing states that are roughly the same distance from Longview and New Orleans, such as Minnesota, the third highest soybean producer in the United States.

The Longview facility is likely to compete with Gulf Coast ports in grain-producing states that are roughly the same distance from Longview and New Orleans, such as Minnesota, the third highest soybean producer in the United States.

Minnesota, which exports half of its soybean yield, barges the crops down the Mississippi River to ports along the Gulf Coast, said Mike O'Leary, a soybean grower in Danvers, Minn., in the western part of the state near South Dakota.

The new Longview terminal is good for growers who ship their crop to the Pacific Northwest by rail, O'Leary said.

"It's going to create competition on the West Coast, and (farmers) can probably get a better price for their product," said O'Leary, chairman of the international marketing committee of the Minnesota Soybean Growers Association.

Growers in Eastern Minnesota send their beans on barges to Gulf Coast ports in Louisiana because it's less expensive, he said.

"The driving thing is freight costs, and water traffic is the cheapest," O'Leary said.

Down in Louisiana, deep-sea ports benefit from the expansive Mississippi River system, which, along with its tributaries, touches 30 states through the heart of country, said Glen Schnexnayder, vice president of sales for Associated Terminals, which operates five terminals in the Gulf Coast.

A new terminal in Longview could take some grain business away from the Southeastern ports, but the reach of the Mississippi River keeps the area competitive, he said, Schnexnayder said.

The Columbia River became attractive to Bunge because of the $150 million project to deepen the Columbia River by three feet from Astoria to Portland, EGT officials say.

The Longview terminal, expected to be completed next year, allows ships to haul full loads of cargo through the deepened channel, which means higher profits for the grain companies. It's the first export grain terminal built in the U.S. in 25 years.

"They wouldn't be doing it if they didn't see a need for it," said Ken O'Hollaren, Port of Longview director.

The terminal is also a big win for the Longview area, O'Hollaren added. The terminal will add 50 permanent longshore jobs and 30 related jobs to Longview.

Construction is expected to bring about 200 jobs to the area over the next two years. Minnesota-based T.E. Ibberson, the general contractor, has hired 13 subcontractors, and eight are based in Southwest Washington and Oregon, said Gary Bennett, a company spokesman.

Local union officials have expressed concern that not enough jobs are going to local workers.

The added lease revenue could give the port the financial flexibility to eliminate its tax levy, which costs the typical home owner about $60 per year for a $150,000 house, O'Hollaren said. Upon completion of the grain terminal, EGT will pay the port about $384,000 in annual lease payments, according to the port.

The addition, to a high-value of the terminal will generate extra property taxes, though the county assessor's office has no estimate yet of the facility's annual tax bill.

Also, it shows other industries that Cowlitz County is a good place to expand their business, said Ted Sprague, president of the Cowlitz Economic Development Council.

"It is an example of an international company, or a consortium of companies, choosing our area," he said.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum