forum

library

tutorial

contact

The Past and Future of Western Dams

by Joseph TaylorHigh Country News, June 6, 2011

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

The Past and Future of Western Dams

by Joseph TaylorHigh Country News, June 6, 2011 |

The turbines have stilled on the Elwha. Upstream from Port Angeles on Washington State's Olympic Peninsula, we are finally seeing the material effects of a very long campaign to tear down the Elwha and Glines Canyon Dams. These aging structures, which are part of a broader infrastructural crisis around the West, have blocked storied salmon runs since 1913, and critics have sought to eliminate them since the 1960s.

The turbines have stilled on the Elwha. Upstream from Port Angeles on Washington State's Olympic Peninsula, we are finally seeing the material effects of a very long campaign to tear down the Elwha and Glines Canyon Dams. These aging structures, which are part of a broader infrastructural crisis around the West, have blocked storied salmon runs since 1913, and critics have sought to eliminate them since the 1960s.

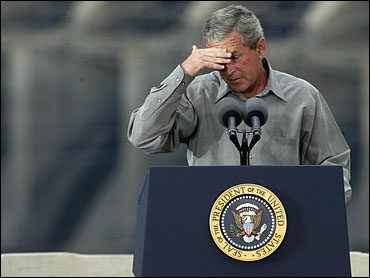

In 1992 opponents seemingly won when President George H. W. Bush authorized removal of the dams, yet only on Wednesday did that process actually begin. Along with the Marmot Dam on the Sandy River, and Gold Hill, Savage Rapids, and Gold Ray Dams on the Rogue River, and with the scheduled end of the Condit Dam on the Big White Salmon and an agreement to tear down four dams on the Klamath River, dam removal seems like an accelerating trend in the Pacific Northwest, yet the history of those Elwha dams contains many lessons, which are not always mutually compatible.

Among the insights is that removal can be a long and bruising process. On a political level, action has happened fastest when there has been broad consensus about removal and when material problems such as replacement opportunities for energy and irrigation are effectively addressed. Even then, however, opponents have managed to delay actions--in some cases by decades--through legislative and litigious resistance. It takes impressive commitment by broad majorities--not 51 percent--to see a process through.

Another lesson is that dams alter nature in ways not always reversible. When engineers opened Marmot, they let the Sandy River scour the impounded sediments because there was little toxic pollution in the watershed. The tactic worked with stunning speed, rapidly developing a natural streambed, but the history of other watersheds preclude such options. The discovery of significant heavy metals and volatile organic compounds slowed and, in some cases, halted dam removal in New England.

At Milltown Dam on Montana's Clark Fork River, breaching went forward due to strong, widespread support, but sediment removal became the largest single cost on a relatively small dam and reservoir. The Elwha dams are larger with much deeper sediments that may contain run-off from nineteenth-century mining activities. Other basins reveal even graver legacies. Chemical tests suggest toxicity is not a concern in the Klamath, but industrial barging, mining, and agriculture will complicate dam removal in the lower Snake River Basin. The battle over the latest Biological Plan for Columbia Basin salmon ensures that the "salmon wars" will sustain discussion about dam removal, but the contingent histories of individual dams ensures that no policy is inevitable.

This is the most important lesson history offers. Contrary to the pithy sayings of George Santayana ("Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it") and Karl Marx ("History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce"), the past does not repeat itself. Nature and society have been undergoing constant evolution. The contexts change, ensuring that neither we nor nature can reverse course to some preexisting, idyllic state, and that we must learn to live with how the past has constrained our present and future.

This insight is critical for thinking about environmental issues. Although it is crucial to know as much as possible about the past of dammed watersheds, the larger, more important lesson for me is recognizing how the contingencies of time and space have propelled events in ways our predecessors could not anticipate. History shows over and over that we are rather incompetent fortune tellers.

Take for example the undammed Fraser River, in Canada. British Columbians pushed for river development throughout the last century, yet, as Matthew Evenden recounts in Fish versus Power, something always intervened. Decade after decade economic downturns, fishery protests, technological limitations, international diplomacy, and, ultimately, technological innovation kept the river open. Boosters trusted the immutable logic of progress, yet they could not anticipate all the contingencies. Salmon were beneficiaries. The Fraser remains the only major free-running Western river, but not from any farsighted concern about fish.

Therein lies a humbling lesson for salmon advocates. Listening to Tim Palmer or Rocky Barker discuss those four lower Snake dams, I hear an echo of the dam boosters in their belief about the immutable logic of removal. Dam opponents often sound like the missionaries who visit on Saturday afternoon. They know truth, and they are here to convert. I experienced this in spades after my piece in April on how technological changes at Round Butte Dam is possibly altering old assumptions about dams. One reader accused me of drinking the "Kool-Aid," and an editor wanted to know if I was really arguing that "we should throw in the towel on salmon recovery." I privately assured both I wasn't stoned and I still cared about wild salmon, but the exchanges reminded me that our ideas about nature reflect faith as much as science.

This can lead to intellectual rigidity, which is a liability in times of flux, and right now the historian in me thinks that environmental, social, and technological contexts are changing rapidly. As much as we might wish otherwise, this winter's massive snowpack is not the new normal. Every climatological study sees the West getting more arid and more energy intensive over the next century, and the latest census reveals the West--already the most urban region of the country--is growing ever more urban.

Combine this with a report of significant declines in groundwater storage, and it sounds like westerners will be more, not less, dependent on dams to capture winter precipitation for drinking and irrigation. The energy grid is growing more diverse, with solar and wind providing a larger amounts of the supply and hydroelectricity also growing as smaller federal and private are retrofitted for generation. Each of these sources has an appeal because of the low carbon emission but also environmental costs. Solar arrays affect habit and construction produces toxic wastes and dependence on rare earth minerals from China. Wind generators take a toll on birds and annoy neighbors with sound pollution.

The litany of problems attending dams is legion and well known. They delay adult and juvenile salmon migration and enhance opportunities for predation. Impounded reservoirs are unnaturally warm. Spillways supersaturate nitrogen content. Turbines chew fish to bits. Dams are fish killers, no doubt about it, but to listen to dam opponents, you would think that engineers are at best dense and at worse malicious, yet the long list of technological innovations in the last two decades, many of which were forced by deserved pillorying of water management agencies and the application of Endangered Species Act listings, has had real effects. Screens are more effective , spills are better regulated, transport is better measured , and research is ongoing. I am not Dr. Pangloss. Real problems persist, but dam technology has not been static. The work at Round Butte Dam involves technologies that might be scalable to bigger or smaller reservoirs and thus vastly increase juvenile fish survival at dams. Studies there and elsewhere also show that structures as varied as Glen Canyon Dam and agricultural impoundments on the Canadian prairies can manage downstream water quality and temperatures, which will be increasingly important for fish species as the snowpack goes away.

The connection between the past and future is never a straight line. It is hard enough for me to connect the dots to the past, let alone the future, but the thing that keeps forcing me to reconsider dams and their role in the West is that only they address both the issue of power and water. Critics of the Bureau of Reclamation like to point out that the agency, which has a vested interest in building dams, has a long history of forecasting a need for more dams, but I know of no one who thinks the West won't get drier and more populous in the coming decades. Nor do I know anyone who thinks conservation measures can ameliorate all the coming stresses. With declining snowpacks and groundwater storage, it seems incumbent on dam opponents to explain how to offset the pressures of growth and aridity and climate change and warming rivers other than wishing people would go away.

Essays in the Range blog are not written by High Country News. The authors are solely responsible for the content.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum